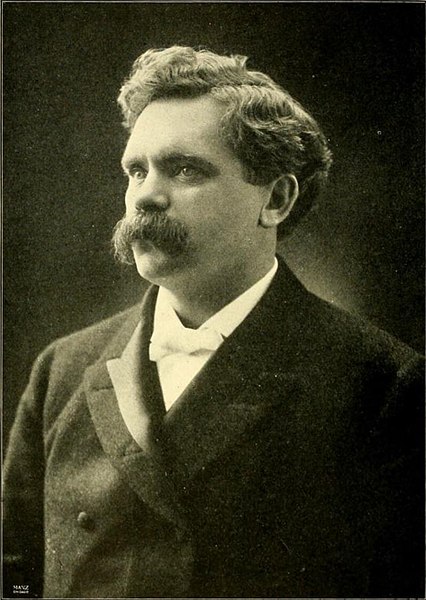

The year is 1906 and B.H. Roberts, a senior official in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day saints,[1] is not a happy camper. To be precise, he is appalled at the lack of critical thinking on the part of the members of the church and some of his colleagues. And he has just said so publicly. What set him off?

A few years earlier, Roberts, under the direction of the First Presidency of the Church, had authored a manual for the church’s young men’s organization wherein he had rejected the prevailing view regarding the manner in which Joseph Smith had translated the Book of Mormon from certain plates he had found buried in a hill in Upstate New York. All were in agreement that Joseph lacked the ability to read the characters on the plates and “translate” them in the customary sense of the word. But Roberts views regarding how Smith had composed the book were controversial in the eyes of many, precipitating “considerable discussion within the Church.”[2]

Roberts argued for what some call the “Composed Translation Method.” Here, the prophet viewed the characters in a seer stone with the aid of the ancient instruments he had found when he discovered the plates.

Next, he summoned all the powers of his intellect to divine their meaning, and then he rendered those mental impressions into his native language and dialect.[3]

Previously, the church had embraced what is often referred to as the “Read Only” method of translation, whereby Joseph Smith peered into a seer stone and saw an English translation of a word or phrase, which he then dictated verbatim. Roberts disparagingly said, “the instruments did all, while he who used them did nothing but look and repeat mechanically what he saw there reflected.”[4]

This idea, according to Roberts, is flawed. Among other things, it fails to explain the hundreds of grammatical errors that subsequently had to be corrected. Further, the presence of numerous nineteenth century anachronisms—what Roberts called “the provincialisms of New York state”—are difficult to reconcile with the notion of a literal translation.[5] And then there are the multiple substantive revisions Joseph made in later editions as his doctrinal understanding began to mature.[6] If he believed what he had originally seen in the stone was the literal word of God, how could he possibly substitute his evolving theological ideas for the “original text”?

Finally, the Read Only theory cannot be reconciled with the manner in which the Lord described the translation process to Joseph and his scribe, Oliver Cowdery. The would-be translator must first “study it out in [his] mind” and then pause to receive spiritual confirmation. If that is not forthcoming and instead you experience a stupor thought, then you have been denied the gift and power to translate.[7] Simply reading a word that appears in a stone and dictating it to a scribe, Roberts said, would not have required the prophet to expend “any intellectual or mental power.”[8] Anyone could have done it.

Most 21st-century Mormons will find this story surprising for two reasons. The first is the open disagreement and passionate debates among both members and leaders of the church on this issue. This was not unusual during the first 100 years of the Church’s history, so no one found it troubling. Church members were resilient and were accustomed to theological disagreements among their leaders. Indeed, many found these different perspectives beneficial in helping them form their own opinions.

The second striking element in this historical episode is Roberts’ emphasis on the importance of critical thinking and his despair at its absence in the church. He longed for the day when “our own people would approach the consideration of the matter [the question of translation] with less feeling and more reason than they do; …”[9] The Read Only theory, he declared, “could only come into existence and remain so long and now be clung to by some so tenaciously because our fathers and our people in the past and now were and are uncritical.”[10] He continued his lament, saying there is a “crying need” in the church for disciples who can force the faith “beyond its earlier and cruder stages of development.”[11]

But what exactly is this “critical thinking” that Roberts believed is so essential to understanding the manner in which Joseph Smith produced the Book of Mormon and all other facets of the gospel of Jesus Christ?

Critical thinking always begins with a question, a doubt or a suspicion, be it metaphysical or temporal. What is the best way to organize a society? Is our school lunch policy accomplishing its intended objectives? Once you have framed your hypothesis, you gather information: facts, evidence, statistics, and all other observations relevant to your inquiry. This may also include the opinions and studies of experts in the field.

Finally, you analyze the data and opinions you have collected, a process requiring extensive reading, study, analysis and contemplation. If you are of a religious mindset, meditation and prayer may provide you with insight. But you never approach the question before you with the intention of validating your beliefs, be they religious, economic, social or political. Rather, your sole objective is to ascertain the truth to the best of your ability.

Your thinking, however, does not stop there. You must remain open to the possibility that the conclusions you have reached are wrong. While your initial analysis and recommendations may have been correct, a course correction may be required in the future. You may cherish your beliefs and convictions, but caution and changing circumstances argue in favor of reexamining them from time to time.

Let’s face it: this is a labor-intensive, time-consuming process. Most folks shy away from it, except when absolutely necessary. Indeed, there have been many times in history when people happily agreed to allow others to relieve them of this responsibility.

The decentralized government created by Joshua for the Israelites, where power was dispersed among several judges and each member of the community was given certain responsibilities, was jettisoned by the Israelites in favor of a king so he could fight their battles for them, even if it meant paying onerous taxes.[12] The Romans replaced their republic, where all male citizens elected the government’s representatives, with an empire because multiple civil wars persuaded them to exchange their freedom for autocracy.[13] And some members of the Continental Army implored George Washington to be their monarch since they were convinced that republics are inherently weak and inefficient.[14]

To the best of my knowledge, over the past 120 years no other church leader has issued such a clarion call for critical thinking than B.H. Roberts—with the noteworthy exception of President Hugh B. Brown, First Counselor to President David O. McKay.

In his memoirs he declared, “[T]here are altogether too many people in the world who are willing to accept as true whatever is printed in a book or delivered from a pulpit. Their faith never goes below the surface soil of authority.”[15]

The antidote for such shallowness of mind, according to President Brown, is for all men and women to develop what he called “the questing spirit”—to shed all fear “of new ideas” and to realize that those ideas are often “stepping stones to progress.” He is careful to remind us to respect the opinions of others, and to be humble and teachable. But in the same breath he states that we should be unafraid to dissent, that we “should be dauntless in our pursuit of truth and resist all demands for unthinking conformity.”[16] Truth was Brown’s lode star: “The honest investigator … must, with fearless and open mind insist that facts are more important than any cherished, mistaken beliefs, no matter how unpleasant the facts or how delightful the beliefs.”[17]

While delivering the commencement address at the Church College of Hawaii (now BYU Hawaii) in 1969, he reiterated the importance of critical thinking even more forcefully, urging each graduate to persevere “the freedom of your mind in education and in religion, and be unafraid to express your thoughts and to insist upon your right to examine every proposition.”[18] Sadly, Brown’s exhortation to always maintain a questing spirit, along with Roberts’ lament about the paucity of critical thinking in the church, have often fallen on deaf ears.

Hugh Nibley, a professor of religion and history at BYU for almost fifty years, penned an essay in 1978, titled “Zeal Without Knowledge,” in which he expressed dismay about the countless students he and his colleagues had encountered over the years who seemed devoid of intellectual curiosity. Not infrequently, students would “come to a teacher, usually at the beginning of a term, with the sincere request that he refrain from teaching them anything new. They have no desire, they explain, to hear what they do not know already.” He said he could not “imagine that happening at any other school, …”[19]

But it wasn’t just young adults who were uninterested in the rigors of intellectual thought. Church members not infrequently told Nibley how they had interpreted an historical artifact or had been led to an archaeological discovery as a direct answer to prayer. When he had the temerity to question the accuracy of their interpretation or the authenticity of their discovery, they felt as if he was questioning the reality of their revelation. Sometimes they even refused to allow Nibley to scrutinize their claims, saying they must be true since they had “been the means of bringing people to the church.”[20]

In 2012, Ben Spackman, a noted Mormon scholar, also encountered this same unquestioning, uncritical mindset while teaching at BYU. He wondered whether, given the authoritarian structure of the church, students came to the university expecting “Pure Truth” to be bestowed by The Authorities (i.e., professors) on those less enlightened (i.e., students), instead of learning how to engage data and arguments.”[21]

One of the best resources at our disposal for teaching our youth how to think critically is the scriptures—provided we accept them on their own terms, not ours. To do that, we must acquaint ourselves with the culture of the authors of these texts and learn to identify the many different genres they employed, such as poetry, myth, parables, law codes, satire, songs, wisdom literature, prophecy and history. We must refrain from forcing the text to conform to our religious beliefs and, instead, focus on understanding how the author perceived the world and what message he was trying convey. Finally, in the words of President Dieter Uchtdorf, we must interrogate the scriptures, tear down “the massive, iron gate of what we thought we already knew,” and open our minds to new possibilities.[22]

With this mindset, we discover that a simplistic, literalistic and superficial reading of scripture frequently obscures its true meaning.

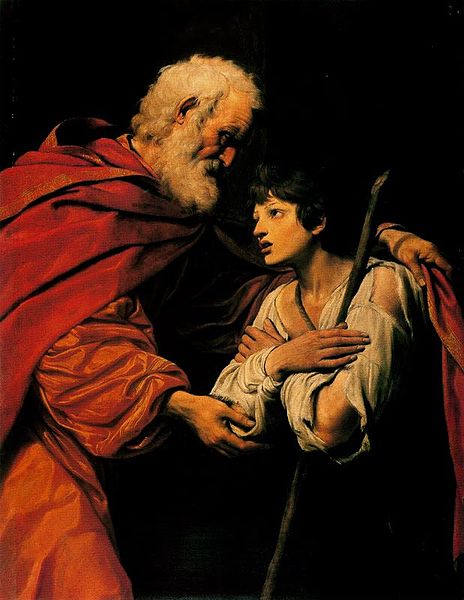

A contextual reading of the story of the prodigal son, for example, reveals that multiple characters are in need of repentance and that there is reason to doubt the sincerity of the wayward younger brother’s commitment to change his ways.[23] Perhaps we should also reconsider whether Christ’s response to the Pharisees’ question—“Whether it is lawful to pay taxes to Caesar?”—really means that everyone should be good citizens and pay their taxes, as stated in the church’s seminary manual.[24] (Spoiler alert: It doesn’t.[25])

Did Eve really make a “wise choice” when she partook of the forbidden fruit, or are her actions open to question, as I and others have suggested?[26] And what about Abraham’s decision to sacrifice his son Isaac? Isn’t this the same man who earlier argued with God—and won—about the fairness of incinerating the righteous in Sodom (Abraham’s cousin Lot and his family) along with the wicked? And did Lot actually engage in incest with his two daughters immediately afterwards, or was this Israelite propaganda designed to disparage its enemies by claiming they descended from those forbidden unions?[27]

The prospect of thinking critically about the scriptures can seem daunting. Why can’t we just be given the answer key, or least a checklist with boxes we can tick, so that when our time is up, St. Peter will let us through the pearly gates? But as Hugh Nibley taught, our sacred texts were never intended to be an “answer book.” And the scriptures say so themselves.

In Proverbs we read: “Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore get wisdom: and with all thy getting get understanding.”[28] The path to wisdom is charted in the final two words of this inspired aphorism: “get understanding.” But understanding of what? Everything. Why do nations go to war? What are dark matter and dark energy? Why are the silences (i.e., the rests) in Beethoven’s music so hypnotic? What did Christ mean when he said, “the meek shall inherit the earth”? And what is meekness?

In other words, the extent of our wisdom is commensurate with our efforts to seek after knowledge and understanding regarding all aspects of creation, both temporal and celestial. Out of necessity, that quest begins with critical thinking: wide and deep reading, arduous study, contemplation, and constant self-examination. Yes, as Joseph Smith taught, we need “revelation to assist us, and give us knowledge of the things of God,”[29] but, as Nibley cautioned, “only the hard worker can expect such assistance.”[30]

The scriptures—along with the master works of literature and history, the authors of which David O. McKay referred to as “the minor prophets”[31]—are not an instruction manual or an answer book, nor do they provide us with a list of things we should do to secure our salvation. Rather, as noted by the writer Joyce Carol Oates, one of the reasons we read these great works is because they are “the sole means by which we slip, involuntarily, often helplessly, into another’s skin, another’s voice, another’s soul.”[32] In the process, we come to understand the culture and values of others and sympathize with their struggles and frustrations. And we expand our own horizons and discover new ideas to explore.

As astutely noted by the writer and social commentator William Deresiewicz, no one ever masters the scriptures, Shakespeare, Plato, Milton or Austen. But therein lies their eternal value. We come back to them again and again not in search of answers but because of the questions they force upon us—“Who am I? How should I live my life? What does it mean to love my neighbor as myself?”[33]

These questions, if they are to be answered, require us to think critically which, in turn, teaches us how to ask better questions in our search for answers. We, like Eve, Abraham and Jacob, must wrestle with the angel in order to divine the meaning of God’s will in our lives. Perhaps the correctness of the decisions we make—along with those made by Eve and Abraham—is secondary to the sincerity and intensity with which we seek wisdom before acting and our willingness to accept the consequences of our choices.

The venue where you are most likely to witness critical thinking in our church, in my opinion, is not Sunday school, a seminary class or General Conference, but Primary. Young children have not yet been schooled in “right thinking” or warned of the evils of “wrong thinking.” They see with fresh eyes and notice when something is out of place. And there is not a single question they will hesitate to ask.

I have witnessed this play out on many occasions and so have some of my friends. One of my favorite stories in this regard, which I have shared before, was related to me by someone who I shall call “Ruth.” While teaching her Primary class about Christ in Gethsemane, she read the verse in Luke about Jesus, who in anguish while praying in the garden, began to perspire, “Then His sweat became like great drops of blood falling down to the ground.”[34]

When she finished, one little girl inquisitorially asked: “If he was sweating blood all over the place, why didn’t the disciples, when Jesus rejoined them, say, ‘Ew! What’s that smell? And why are your clothes all soaking wet and red?’” Ruth smiled and pointed out that Luke was simply making a comparison. He didn’t mean Jesus was actually bleeding; rather, he was saying that Jesus’ “sweat became like great drops of blood.”

But another little girl, whose father happened to be one of the local leaders, emphatically declared: “My dad said a general authority has testified that Jesus really was bleeding. And he actually bled from every pore on his body!” Ruth responded respectfully to the child’s comment—after all, she’d heard similar statements from the pulpit before—but continued to underscore the comparative nature of this passage from Luke.

That our Primary teacher, Ruth, did not read Luke 22:44 as actually describing the sweating of blood by the Savior proved unacceptable. Word of her heresy reached the powers-that-be, and, thereafter, a member of the bishopric regularly attended her class. Not surprisingly, this had a chilling effect on her lesson presentations and most likely on class participation. Two months later she was released from her calling and given another.

So, was this little girl right? I, along with the majority of biblical scholars, believe she was, as I explained in a previous essay.[35] But why, for crying out loud, does the color of Christ’s perspiration matter? Does the efficacy of the atonement hinge on the consistency of the Son of Man’s sweat?!? And are compelling the conformity of a teacher and discouraging the inquisitiveness of a child what we want to be known for?

Shortly after delivering the Sermon on the Mount, Christ said, “‘suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me: for of such are the kingdom of heaven.’”[36] We often interpret this passage to underscore the importance of being “teachable,” like a child. But that is only half of the equation. What makes a child teachable is her insatiable curiosity, her endless questions, and her limitless imagination. I can think of no better synonym for critical thinking than “an imagination allowed to run wild.” And that’s not work. That’s fun!

[1] Roberts was one of the seven presidents of First Council of the Seventy, the third-highest governing body of the Mormon church.

[2] B. H. Roberts, New Witnesses for God II: The Book of Mormon, vol. 2 of 3, (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret News, 1909), note u.

[3] John-Charles Duffy, “The ‘Book of Mormon Translation:’ Essay in Historical Context,” appearing in, The LDS Gospel Topics Series: A Scholarly Engagement,Matthew L. Harris and Newell G. Bringhurst, eds., (Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 2020), p. 102.

[4]Ibid, pp. 101-102.

[5] B. H. Roberts, “Book of Mormon Translation—Correspondence,” Improvement Era, July 1906, p. 711. Certain individuals who, on occasion, witnessed Smith engage in the translation process (e.g., Martin Harris) give some credence to the Read Only theory. Roberts, however, effectively discredits much of their testimony by noting, among other things, the inconsistencies in the accounts and questioning their reliability because some of them were hearsay and were not recorded until decades after the fact.

[6] Eric F. Facer, “Making Sense of the First Vision,” A Well Examined Life, March 20, 2021, https://thewellexaminedlife.com/making-sense-of-the-first-vision/Joseph’s revisions to the Bible also reflect the evolution of his understanding of various points of doctrine, including the nature of the Godhead.

[7] D&C 9:8.

[8] “Translation Correspondence,” p. 708.

[9] Ibid, p. 712 (emphasis added).

[10] Ibid, p. 711 (emphasis added) Roberts is quoting John Fiske, a liberal Christian philosopher of the late 19th century.

[11] Ibid, p. 712. Arguably, no other leader in the history of the church has felt more passionately about the Book of Mormon than B.H. Roberts

[12] 1 Samuel 8:5-20.

[13] Edward J. Watts, Mortal Republic: How Rome Fell Into Tyranny, (New York, New York: Basic Books, 2018).

[14] Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life, (New York, New York: The Penguin Press, 2010), p. 428.

[15] Hugh B. Brown, Edwin B. Firmage, ed., An Abundant Life: The Memoirs of Hugh B. Brown, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 1999), pp. 135-136.

[16] Edward B. Firmage, The Memoirs of Hugh B. Brown: An Abundant Life, pp. 135-140 (Signature Books 1988).

[17] Hugh B. Brown, Second Counselor in the First Presidency, General Conference, October 1962.

[18] Hugh B. Brown, “An Eternal Quest—Freedom of the Mind,” commencement address given at the Church College of Hawaii (now BYU Hawaii), May 13, 1969, reprinted in Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, vol. 17, no. 1 (Spring 1984), pp. 77-83.

[19] Hugh W. Nibley, “Zeal Without Knowledge,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, vol. 11, no. 2 (Summer 1978), p. 108.

[20] Ibid, p. 107.

[21] Ben Spackman, “The Standard Packet, the Book of Mormon and Critical Thinking at BYU,” Times and Seasons, January 20, 212, https://www.timesandseasons.org/harchive/2012/01/the-standard-packet-the-book-of-mormon-and-critical-thinking-at-byu/

[22] Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Acting on the Truths of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, “Worldwide Leadership Training Conference, February 2012, https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/broadcasts/article/worldwide-leadership-training/2012/01/acting-on-the-truths-of-the-gospel-of-jesus-christ?lang=eng

[23] Eric F. Facer, “The Dysfunctional Family of Man,” A Well Examined Life, June 14, 2020.

[24] “New Testament Seminary Teacher Manual,” Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Lesson 25 (2023),https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/new-testament-seminary-teacher-manual/matthew/lesson-25-matthew-22-15-46?lang=eng

[25] Eric F. Facer, “When Caesar and God Collide,” A Well Examined Life, June 20, 2020, https://thewellexaminedlife.com/when-caesar-and-god-collide/

[26] Eric F. Facer, “Did Eve Make a ‘Wise Choice’”?, A Well Examined Life, March 19, 2022, https://thewellexaminedlife.com/did-eve-make-a-wise-choice/ In a subsequent essay, I argue that Eve’s actions were not a “wise choice” but A Praiseworthy Rebellion, https://thewellexaminedlife.com/a-praiseworthy-rebellion/

[27] Eric F. Facer, “Incest,” A Well Examined Life, November 2, 2020, https://thewellexaminedlife.com/incest/

[28] Proverbs 4:7 (KJV).

[29] Teachings, p. 217.

[30] Zeal Without Knowledge, p. 107.

[31] Elder Douglas L. Callister (of the Seventy), “Our Refined Heavenly Home,” devotional address given at Brigham Young University, September 19, 2006, https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/douglas-l-callister/refined-heavenly-home/

[32] Quoted by Karen Swallow Prior in, “How Reading Makes Us Human,” The Atlantic, June 21, 2013.

[33] William Deresiewicz, The End of Solitude: Selected Essays on Culture and Society, (New York, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2022), pp. 110-111.

[34] Luke 22:24 (NKJV).

[35] Eric F. Facer, “Sweating Blood,” A Well Examined Life, https://thewellexaminedlife.com/sweating-blood/

[36] Matthew 19:14 (KJV).

A very good article and I look forward to part 2. But talk about a Sisyphean task!

Fascinating. I look forward to part II. Paul noted that we as humans cannot be certain about our knowledge or understanding (or at least that’s my understanding of the implications of this passage): “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.” I Corinthians 13:12.

Very very interesting. It gives us a lot to think about but then that is the point!

Doug, I think that’s a fair interpretation, though several modern translations render this verse differently in one key respect: “For now we see in a mirror dimly, then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known.” [NSRV]

The mirrors used in the Roman world were formed by a disc of polished metal, not glass, so the reflected image was obscure, at best. So perhaps Paul is telling us that our spiritual understanding is not just about those things around us we do not understand, but also seeing ourselves more honestly. Frankly, there is nothing more difficult, in my opinion, than self-assessment.

There is another passage from Corinthians I believe captures the point you are making: “We are troubled on every side, yet not distressed; we are perplexed, but not in despair.” (2 Corin. 4:8, KJV)

For Paul, the many paradoxes and mysteries in the scriptures were befuddling, and perhaps insoluble. But he didn’t give up. He didn’t try to sand off the inconsistencies and ambiguities he found in the Bible or Christ’s teachings; instead, he was prepared not only to live with them but to puzzle and puzzle even after his puzzler is sore.

Thanks again for sharing your thoughts. I always appreciate it.

Reminds me of Rev. Benjamin Cremer when he said, “ Christianity should look more like questions in search for answers, not answers that aren’t allowed to be questioned.”

Your words remind me that I am not alone and give me a brief rest while navigating this struggle. Ruth’s experience echos my own. I whole heartedly say amen and thank you for putting these reflections into words!

Christine, thank you so much for taking the time to read this piece and share your thoughts. Your words serve to remind me that I’m not alone. And that counts for a lot.