The Synoptic Gospels—Matthew, Mark and Luke—are so called because they each relate many of the same stories when recounting the life and ministry of the Savior, and do so in a similar sequence. John’s gospel, by contrast, is different. Radically different.

The Gospel of John is a meticulously structured work that is more symbolic than historical in nature. His account of Christ’s ministry is highly schematic. It consists primarily of: (1) “seven signs,” the last of which—the raising of Lazarus—foreshadows his resurrection, and (2) seven “I am” discourses where Jesus forcefully lays claim to his role as the Messiah.

The representational nature of many of the stories found in John, combined with the gospel’s deep roots in the Old Testament, make it difficult, at times, to divine its message. And few passages are more challenging than the evangelist’s portrayal of the Savior’s mother.

Mary makes only two appearances in John’s gospel: at the beginning during the wedding at Cana—the first of the “seven signs”—and at the end, standing at the foot of the cross beside “the disciple whom Jesus loved.” Neither of these episodes, however, is recounted in the Synoptic Gospels. This, combined with the fact that John never refers to Mary by name but only as “the Mother of Jesus,” suggests she is a symbolic character in these stories. But a symbol of what? Unraveling that mystery starts with a Galilean wedding where the host finds himself in an embarrassing situation: he has run out of wine.

On the third day there was a wedding at Cana in Galilee, and the mother of Jesus was there. Jesus also was invited to the wedding with his disciples. When the wine ran out, the mother of Jesus said to him, “They have no wine.” And Jesus said to her, “Woman, what does this have to do with me? My hour has not yet come.” His mother said to the servants, “Do whatever he tells you.”

John 2:1-5 (ESV)

Nearby were six large jugs used for Jewish purification rituals, which Christ instructed the servants to fill with water. When the Master of the Feast sampled their contents he found not just wine but wine in abundance and of the highest quality. This baffled him, so he promptly confronted the bridegroom and exclaimed: “Everyone serves the good wine first, and when people have drunk freely, then the poor wine. But you have kept the good wine until now.”

The host’s remark is an explicit reference to Old Testament prophetic expectations, which envisioned wine flowing in abundance during the messianic age.[1] Also, the coming of the Messiah is often compared in Jewish writings to the days of a wedding feast. So, it is not surprising that the Gospels are replete with stories about weddings, e.g., the wise and foolish virgins;[2] the story of the improperly attired wedding guest;[3] the story of the wedding guests who aren’t pleased with the seating arrangements.[4] The Wedding at Cana differs from these other stories, however, in two respects. First, Christ is not the bridegroom, though he may be symbolically. Second, this is a miracle story that the evangelist employs to reveal certain aspects of the Savior’s messianic mission.[5]

For example, the occurrence of the wedding “on the third day” points to the resurrection, the culmination of Christ’s earthly ministry. Further, the number of purification jars he fills with wine is also significant since “six” in rabbinic numerology symbolizes deficiency—that which falls short—implying that what the priests and the scribes are teaching is only a portion of the truth.[6] And finally, breaking with tradition by serving the best wine at the end of wedding instead of at the beginning intimates that the first and most highly esteemed prophet of the Israelites—Moses—is about to be eclipsed by the arrival of the greatest prophet of all.

But what are we to make of the exchange between Jesus and his mother? This undoubtedly is the most confusing element of the story. Embedded within it and in Mary’s final appearance in John’s gospel, however, is one of Christ’s most profound teachings.

The fact that Mary comes to Jesus for help with the wine problem suggests she is cognizant of his ability to solve it and solve it quickly. But the reader is taken aback by his response: “Woman, what does this have to do with me? My hour has not yet come.” Why is Jesus being so rude?

As a threshold matter, addressing someone as “woman” is not as offensive in Greek as it sounds in our language and culture; rather, it is similar to the English “Ma’am.”[7] The same, however, cannot be said of the Savior’s interrogatory: “What does this have to do with me?” This question clearly suggests a gulf between Jesus and his mother. But this should not surprise us since there are several other passages in the New Testament that imply a disconnect between the Savior and his family.[8]

Further, Jesus’s declaration “My hour [i.e., the appointed time of my death] has not yet come” evinces a concern that if he performs this miracle, his true identity could be prematurely revealed to the world at large. This rebuke notwithstanding, Mary construes Jesus’s words as indicating that he is willing to help, which Christ does discreetly, with nobody discovering from whence the new wine came, save the servants.

This strange dynamic between Jesus and his mother seems to suggest that John is using Mary figuratively as a bridge “between the shortcomings of the ritual activity of the Jews and the celebration of the new life that Jesus came to bring—new life symbolized by the marriage ceremony.”[9] In other words, the wine of the spirit has replaced the waters of purification but the vessels holding the wine remain the same.

While Christ performed this miracle, it was Mary who facilitated its execution. As noted by biblical scholar and Episcopal Bishop John Shelby Spong, the evangelist appears to be employing the woman who brought Jesus into the world as a stand-in for Israel, the faith tradition that gave birth to Christianity.[10] But the full meaning of this metaphor will not be revealed until her second cameo appearance in John’s gospel, at the foot of the cross, to which we now turn.

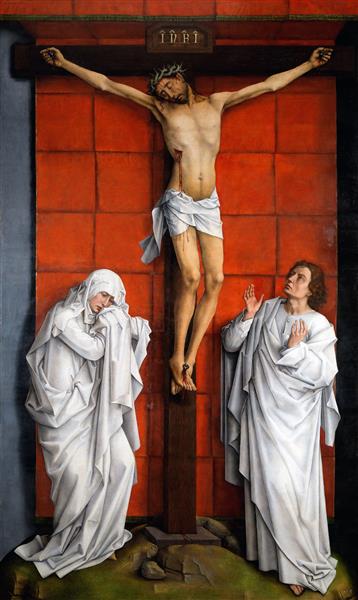

As recorded in John 19, during the final hour of his crucifixion Jesus spied his mother and the “disciple whom he loved” standing nearby:

When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing nearby, he said to his mother, “Woman, behold, your son!” Then he said to the disciple, “Behold, your mother!” And from that hour the disciple took her to his own home.

John 19: 26-27 (ESV).

We typically ascribe no meaning to this passage beyond that of Christ making provision for the care of his mother. But this doesn’t make sense since, under Jewish law and custom, his younger siblings—and the Gospels tell us he had several—would have been charged with this responsibility. Besides, why would John choose to highlight these final words of the Savior if their only significance is to reinforce an uncontroversial teaching accepted by virtually every faith tradition and one never given any prominence during Christ’s ministry: “Honor thy father and thy mother”? No, something more is going on here, something we cannot see unless we realize that both “the disciple whom Jesus loved” and “the mother of Jesus” are emblematic of something much larger.

When we open our minds to this possibility, we discover that “the disciple whom Jesus loved” was not John or anyone else in particular. Rather, he appears to be an archetype for all who follow in our Savior’s footsteps, a symbol of those who respond to his teachings and are transformed. As explained by Bishop Spong, the beloved disciple is anyone who undergoes the spiritual rebirth that Christ explained to Nicodemus.[11] And when we see Mary as symbolic of Judaism and God’s chosen people, then the meaning of the Savior’s words becomes clear.

The Savior’s declaration “Woman, behold, your son!” refers not to himself, but to “the beloved disciple,” to Christ’s loyal followers who have heard and accepted his message. Thus, Christ is making one last attempt to open the eyes of the Jewish nation. In essence, he is saying to his mother/Israel: “Listen, I am about to leave this world, but my disciples—your offspring—can still teach you the fullness of the gospel. Your great gift to the world was preparing the way for my coming; don’t blow it by turning your backs on my gift to you.”[12]

Christ then conveys a similar message when he says to the beloved disciple, “Behold your Mother!”[13] With that forceful admonition, he is telling his followers, “You cannot forget your past. You must accept and cherish the womb (the Jewish faith) that bore you. They are still my chosen people and I expect you to take care of them and overcome the enmity between the two of you.”[14]

The tension between the old and the new that the Savior was describing manifests itself in virtually all aspects of our lives—our families, our work, and our society. And the parent-child relationship invoked by Christ is an apt metaphor for each.

To discern new truths and grow in wisdom and knowledge, we must be teachable like children, “for such is the kingdom of god.”[15] But those who champion the superior vintage of their new ideas must not forget their heritage. Sweeping away tradition, custom and the existing moral order leaves no foundation on which to build a better future. If the new wine causes the purification jars to break, both are lost.

Malachi foreshadowed Christ’s message from the cross to Mary and John when he enjoined the parents and children of the Israelites to turn their hearts toward each other.[16] But I believe the prophet got it wrong when he said Jehovah would strike the land with a curse if they failed to heed his warning. Our destruction will never come at God’s hands, only our own.

[1] See, e.g., Isaiah 25:6; Jeremiah 31:12-14; G. K. Beale and D. A. Carson, Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2007), p. 431.

[2] Matthew 25:1-12.

[3] Matthew 22:11-14.

[4] Luke 14:7-11.

[5] Jeffrey John, The Meaning of the Miracles, (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.: Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2004), p. 47

[6] John Barton and John Muddiman, Editors, The Oxford Bible Commentary, (Oxford University Press: New York, 2001), p. 965.

[7] NKJV Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2017), p. 1877.

[8] See, e.g., Mark 3:21; Luke 11:27.

[9] John Shelby Spong, The Fourth Gospel: Tales of a Jewish Mystic, (HarperOne: New York, 2013), p. 83.

[10] Ibid, p. 84.

[11] Ibid, pp. 251-252.

[12] Ibid, p. 253

[13] John 19:27 (ESV).

[14] The Fourth Gospel, p. 253.

[15] Luke 18:16 (KJV).

[16] Malachi 4:6.