In March 2013, Margaret and I toured Israel with the assistance of our able guide, Daniel Rona. He is, among many other things, a Jew who lost several family members in the Holocaust and who converted to Mormonism when he was young.

Daniel is also knowledgeable, energetic, and entertaining. And quite opinionated (unlike moi). We often debated, history, religion and politics, and loved every minute of it. He said I would have made a good Jew because whenever two Jews argue, they always end up with three opinions (at least). That made my day.

As our stay in the country neared its end, I asked Daniel what his plans were for the following week. Did he have another tour scheduled? His response both surprised and delighted me: “We will be busy preparing for Passover.” Here was a Christian who had no intention of abandoning the customs, beliefs and traditions of his forefathers and who understood their inextricable connection to his Mormon faith.

At sundown today, March 27, 2021, Passover, the most widely celebrated holiday in all of Judaism, begins. It commemorates and celebrates the seminal event of the Old Testament: the liberation of the Jews from bondage and the conception of Israel as a nation.

Thereafter, whenever the Israelites found themselves in a pickle and their faith began to falter, Jehovah never hesitated to remind them, “I am the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.”[1] By my count, there are over 80 such references in the Old Testament. And it doesn’t stop there.

The authors of Matthew’s gospel used this event—and Moses’ starring role—to demonstrate the bona fides of the Savior and explain how his ministry transcends that of the Hebrew Bible’s greatest prophet. The story of the Slaughter of the Innocents—Herod’s infamous attempt to kill the newborn king—is a carefully constructed tale designed to mirror Pharaoh’s efforts to slay the baby Moses. An angelic dream to each child’s caretakers, warning them of the threat, facilitated their escape.[2]

The Christ child’s return to Palestine once the threat had passed is Matthew’s way of attaching a dual meaning to Hosea’s words, “Out of Egypt have I called my Son.”[3] And he continues with this theme when he has Jesus retire to the desert for 40 days of fasting after his baptism—“a symbolic re-enactment of Israel’s forty years in the desert before entering the Promised Land.”[4]

The Passover holiday marks “the beginning of months,”[5] the start of the ecclesiastical Jewish New Year.[6] It takes place in spring: a time of change, rebirth and renewal.[7] And the celebration begins with a Seder, a ceremonial dinner where the participants symbolically relive the flight of the Jews from Egypt.

The purpose of this annual commemoration has its origins in a radical idea articulated by Moses when he met with the Pharaoh to warn him of yet another plague—locusts—if he did not allow the Jews to depart. For the first time the Egyptian ruler began to waver and seemed willing to bargain. “But which ones are to go?” he asked. The prophet’s reply was emphatic: “We will go with our young and our old; we will go with our sons and our daughters….”[8] The Pharaoh, not surprisingly, refused. Without the Jewish youth and their future descendants, his pool of slave labor would quickly evaporate.

While giving priority to children seems only natural to us, in the ancient world it was unheard of. For example, as noted by the Jewish scholar Mark Gerson, Gautama, who would eventually become the Buddha, abandoned his son to pursue enlightenment. Similarly, the sacrificial killing of children was not uncommon in the ancient world; hence, its repeated condemnation in the Hebrew Bible. Indeed, the primacy of adults continued in virtually every society through the Enlightenment.[9]

But propagating, by itself, does not guarantee a culture or religion will endure, and Moses knew it. He also knew that children possess an asset that, if properly channeled, had the ability to ensure the survival of the Jewish people and their faith. So, when he explained the Passover ritual to his people, he encouraged them to nurture in their offspring a trait that is both endearing and annoying: curiosity.

“And when your children ask you, ‘What does this ceremony mean to you?’ then tell them.”[10] Tell them the story, the story of your liberation from the Egyptians and the birth of your nation.[11]

When, not if, your children ask. At a time when most “enlightened” cultures believed children should at best be tolerated, Moses was commanding his people to make them the focus of their Passover celebration, to encourage, not stifle their curiosity, to invite all manner of questions. Since, as Rabbi Joseph Telushkin observed, “The Passover Seder’s goal is nothing less than assuring the Jewish people’s continuity, ”[12] the active participation of the youth was critical.

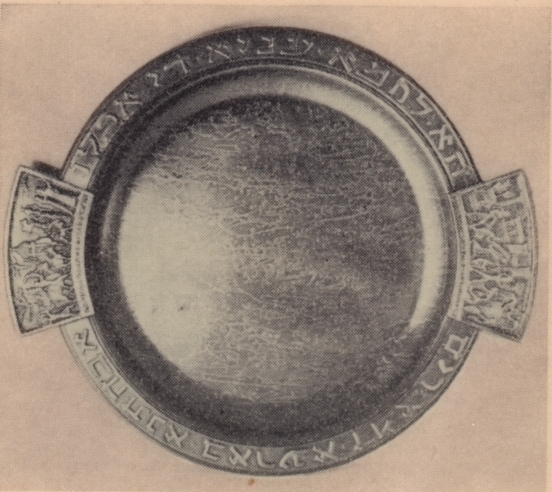

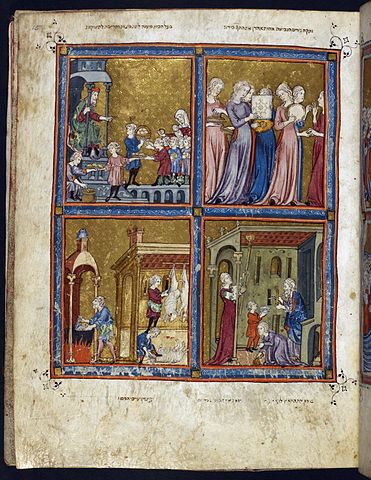

But how should the story be told? The Lord did not say. Nor did Moses. Around 2,000 years ago, however, a few rabbis chose to interpret Jehovah’s admonition by commissioning a short book—the Haggadah (“the Telling”)—to assist the people. Some additional material was added during the Middle Ages, but few changes have been made since.[13]

The Haggadah serves as a script for the Passover Seder. But it is a most peculiar book, containing songs and strange stories, among many other things. While it provides a synopsis of Exodus, it also draws upon the other major books of the Hebrew Bible, yielding what Gerson calls, “The Greatest Hits of Jewish Thought.”[14]

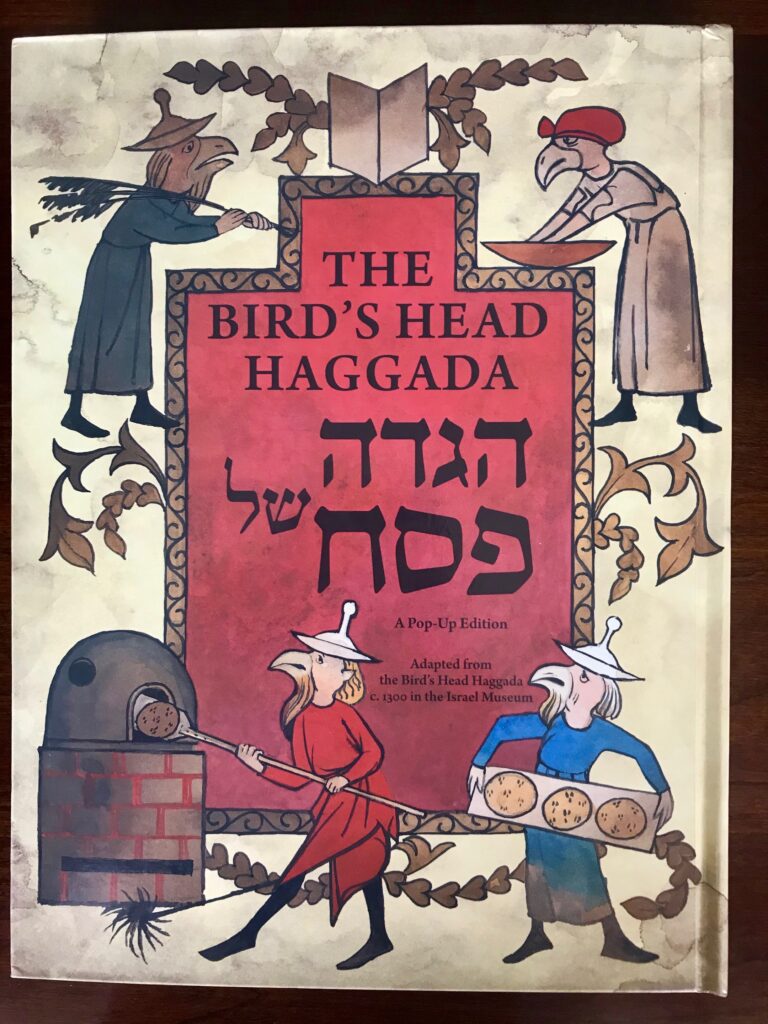

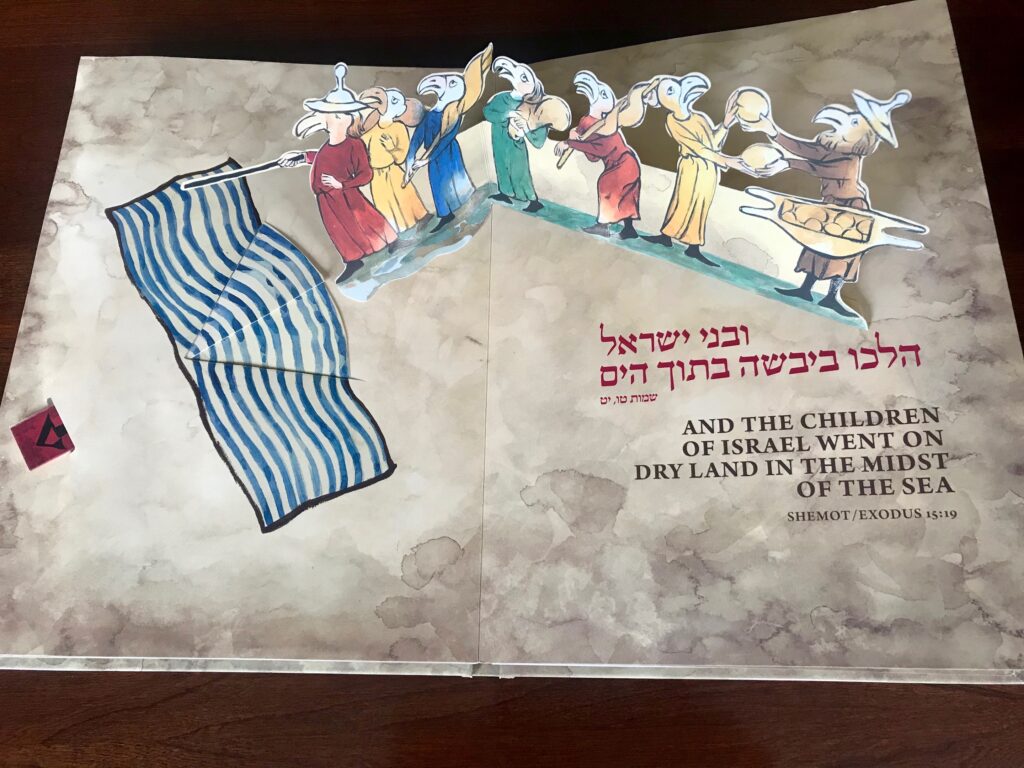

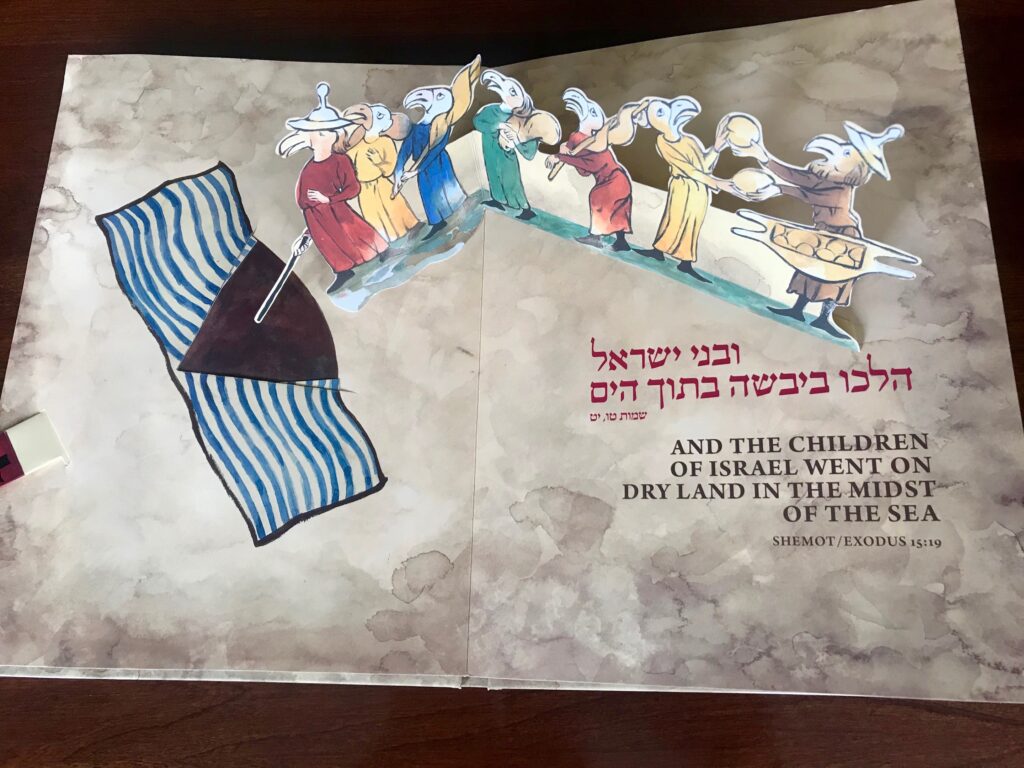

It is a guidebook premised on the notion that “generic instruction does not inspire,”[15] especially children. The user is supposed to adapt and improvise since each child, as Proverbs teaches us, should be taught “according to his way.”[16] Our tour guide, Daniel, as a parting gift gave us a fresh example of this innovative spirit: The Bird’s Head Haggada, a pop-up book for young children.

The Passover Seder teaches through actions, not just words. After the recitation of each of the Ten Plagues, for example, participants sometimes spill some wine, a symbolic expression of the diminution of joy occasioned by the suffering of the Egyptians.[17] And to keep the children engaged (and awake), the adults encourage them to hide the matzah, the last food the Jews are commanded to eat at the Seder and without which the meal cannot be concluded.[18]

The most prominent and well-known feature in the Haggadah is the Ma Nistana: The Four Questions. Traditionally, they are asked via song by the youngest capable child in attendance and each is prefaced by the question, “Why is tonight different from all other nights?” Why…

… on all other nights we eat leavened products and matzah, but on this night only matzah?

… on all other nights we eat all vegetables, but on this night only bitter herbs?

… on all other nights we don’t dip our food even once, but on this night we dip twice?

… on all other nights we eat sitting or reclining, but on this night we only recline?

These questions intentionally contradict the expectations of a child in an observant household. Though there are generally accepted responses to each—for example, bitter herbs are to remind the participants of the time their ancestors were enslaved—they invariably provoke the children to come up with new queries and creative answers of their own. Parents are encouraged to reward a child with a piece of candy or small gift who asks a good question or makes an astute observation. And on this night, there are no bad ones.

This practice not only fosters curiosity; it teaches critical thinking, a hallmark of the Jewish faith. If Abraham, Moses and Job can argue with God, why can’t we? The “authority fallacy”—the notion that something must be true because it is taught by a prophet or rabbi—has little traction in Judaism. The Hebrew Bible teaches that religious leaders sometimes make mistakes and teach something other than the truth. Thus, while they should be respected and are worthy of our attention, their ideas are always open to question, reexamination and debate.

This mindset often yields profound insights. Take, for example, the story of young Henry Foner who, in 1947, resided with his family in the Borough Park section of Brooklyn. That year it fell to him, as the youngest child, to lead the Ma Nistana and ask the Four Questions.

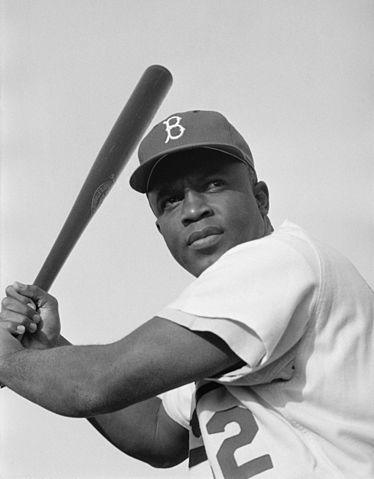

Typically, these questions are answered by the other participants, not the child who poses them. This year, however, when Master Henry asked, “Why is this night different from all other nights?” he promptly said: “Because Jackie Robinson has ascended to the major leagues, to baseball’s promised land.”[19]

Jack Roosevelt Robinson had just joined the Brooklyn Dodgers and was about to become the first African American to play Major League Baseball in the modern era. Henry Foner saw a parallel between the Jews in Egypt and the slavery Robinson’s ancestors had endured and the discrimination he was subjected to as a soldier in the Second World War and as a professional athlete. From now on, every night in Major League Baseball would be different from its predecessors.

The Passover typically concludes with a prayer and an expression of hope for the Messiah: L’Shana Haba’ah b’Yerushalayim! Next year in Jerusalem! This tradition began with the Jews living in the Diaspora who longed to return to their homeland and rebuild the Temple destroyed by the Romans in 70 AD. Today, this proclamation has a more symbolic character. It is an expression of an ongoing quest, individually and collectively, to attain spiritual perfection. Fittingly, the word “Jerusalem” connotes peace (shalom) and completeness (shaleim).

Next year in Jerusalem! Next year in Mecca! Next year in Rome! Next year in Zion! These are not places; rather, the Haggadah teaches that each is a state of mind, an ideal, an aspiration. We draw nearer to the Promised Land and our goal of spiritual perfection when we live Jehovah’s second great commandment without reservation or qualification. Henry Foner understood this better than most.

[1] Deuteronomy 5:6.

[2] Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, (New York: Doubleday, 1993), pp. 213, 615-616.

[3] Hosea 11:1.

[4] The Birth of the Messiah, p. 215.

[5] Exodus 12:2.

[6] Rosh Hashanah, by contrast, marks the beginning of the civil new year and is considered the anniversary of the creation of Adam and Eve.

[7] Leon R. Kass, Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2021), pp. 167-168.

[8] Exodus 10:9 (NSRV).

[9] Mark Gerson, The Telling: How Judaism’s Essential Book Reveals the Meaning of Life, (New York: St. Martins Publishing Group, 2021), p. 28

[10] Exodus 12:26 (NIV).

[11] Exodus 13:8, 14-15.

[12] Rabbi Joseph Telushkin, Jewish Wisdom: Ethical, Spiritual and Historical Lessons from the Great Works and Thinkers, (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1994), p. 385.

[13] Literacy, p. 643.

[14] The Telling, p. 13.

[15] Mark Gerson, “Passover and the Power of Jewish Continuity,” Wall Street Journal, March 20, 2021.

[16] Proverbs 22:6.

[17] Rabbi Joseph Telushkin, Biblical Literacy: The Most Impotent People, Events, and Ideas in the Hebrew Bible,(New York: HarperCollins, 1997), p. 111.

[18] Rabbi Joseph Telushkin, Jewish Literacy: The Most Important Things to Know About the Jewish Religion, (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), p. 646.

[19] Jonathan Eig, Opening Day, The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007), p. 156.

I love how you tie things together. Beautiful. Next year in the promised land!

Thanks, Sarah. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Some folks think the connections I make are sometimes a bit eccentric, but that would be consistent with my personality, so I can’t argue with them.

Well said. An apt reminder for Passover. I went to a Passover Seder at one of our daughter’s friends home a few years ago and really enjoyed it. This friend sand carols with us and came to our Christmas Eve events. It was a meaningful opportunity to share special remembrances and heritage from the Bible. My niece, who is a member of our church, always has a special event for her family to celebrate and remember Passover. I love incorporating this into our lives.

That’s a wonderful tradition your niece has adopted, Karen. Worthy of emulation.

When I moved away from home, my mother told me, “Don’t forget your roots.” Those “roots,” I have learned, travel in many different directions and help keep me grounded.

Eric How true. Roots give us depth and strength. They help hold our lives together. Family and traditions make it possible for us to fit into a place in life. They support us and though it is hard to realize, they also continue to grow and develop.

I enjoyed the concept of making children the focal point of passover and teaching them to be curious and critical thinkers.