In 1858, a young woman named Louisa walked to the edge of the Mill Dam in Boston, Massachusetts and contemplated suicide. A self-described spinster, unemployed, and having recently lost a sister to rheumatic heart disease, she didn’t see a way forward. But, as she later told a friend, she stepped back from the abyss because she realized, “There is work for me, and I’ll have it.”[1]

The work she desired was that of a writer, but little was to be found. Her family’s impoverished circumstances, her gender, and the inherent difficulty of penetrating the world of publishing were formidable obstacles. Nevertheless, she did have the good fortune of growing up in the heart of literary New England and, through friends, had access to a vast array of books. In addition, her father interacted socially with poets such as Longfellow and Lowell, and considered Emerson his best friend. Henry David Thoreau even took Louisa and her siblings on nature walks.[2]

Still, she was unable to find magazines or publishers willing to buy her work. Fame was not what she sought; rather, she was simply trying to provide for her mother, who had lived in poverty most of her life. All of this was the source of immense frustration and threatened to ignite her volatile temper. But Louisa was mature enough to realize that she needed an object against which to channel her rage or else it would be her undoing. In April 1861, Jefferson Davis’ Confederacy provided her with a deserving target.

She began by sowing blue shirts for soldiers to wear into battle, but she wanted to do more. In her journal she wrote, “I’ve often longed to see a war.” She wanted to fight, though she knew that was not an option. So she studied a book on gunshot wounds and prepared to go as a nurse.[3]

But Dorothy Dix, the woman who headed the nursing corps, would not accept candidates under the age of 30—she was “worried that dewy-eyed maidens would invade the hospitals in search of slightly damaged husbands.”[4] So Louisa was compelled to wait until November 29, 1862 to submit her application. Less than two weeks later it was approved and she was assigned to the Army of the Potomac.

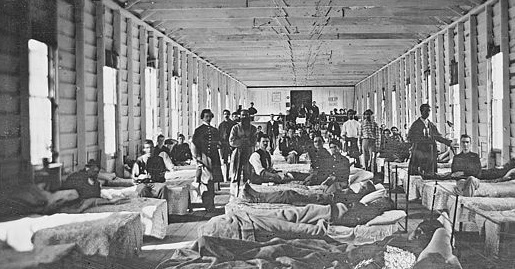

Her first posting was to the Union Hotel Hospital in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. It was one of the poorest hospitals in the North where only enlisted men were treated; officers supposedly deserved better. It served primarily as a way station where the injured could be treated and stabilized before heading north for further medical care.

Instead of experiencing all of the sights and sounds of war, Louisa’s days were filled with repetitious and tedious tasks: feeding the men, administering medicine, and washing faces. All of that was about to change, however. Forty ambulances had just arrived carrying some of the wounded from the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Sixty miles to the south of Washington, the Union Army of the Potomac, led by General Burnside, and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by Robert E. Lee, had locked horns for four days in mid-December 1862. Burnside had hoped to inflict a crippling blow on the South. Instead, poor logistical planning, ill-advised frontal assaults on entrenched positions, and the blunders of the generals under his command resulted in a major defeat. Lee inflicted nearly 13,000 casualties on Burnside’s Army, more than twice those incurred by the South.[5] As Governor Andrew Curtin of Pennsylvania later told President Lincoln, “it was not a battle, it was a butchery.”[6]

The Army of the Potomac was demoralized and men began to desert in droves.[7] The press and the political class, predictably, were questioning Lincoln’s competence. Indeed, members of his own cabinet began to doubt the President’s ability to lead. Though Lincoln did his stoical best to put on a brave face, privately he was distraught. “We are on the brink of destruction,” he wrote a friend. “If there is a worse place than hell, I am in it.”[8]

One of the Union soldiers present at the Battle of Fredericksburg was a young man by the name of Wendell. He hailed from Boston, just 20 miles from Louisa’s family home in Concord. Like Louisa, he was a bibliophile and a disciple of Emerson with literary ambitions of his own.

Shortly before the war, he read Uncle Tom’s Cabin and witnessed firsthand, in his words, the “belittling of a suffering race.”[9] He valued liberty and decency over hierarchy and status, and developed an abiding hatred for slavery. The fall of Fort Sumter demanded a response, and Wendell was prepared to deliver one.

In the summer of 1861 he was given a commission as a lieutenant in the Twentieth Massachusetts Infantry. After his regiment received its allotment of new recruits, it was ordered to Washington. In October of that year, they saw their first action just across the Potomac in the Battle of Ball’s Bluff. It was a disastrous misadventure for the Union forces and Wendell was severely wounded, shot through the chest. The Confederate ball barely missed his heart.[10]

He was sent home to convalesce, but was soon back in action. In March 1862, he participated in McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign and then fought in the West Woods at Antietam, a battle that produced the largest single-day death toll in U.S. military history.[11]

Here Wendell was wounded a second time, shot through the neck. The first doctor to examine him declared, “I’ve no time to waste on dead men.”[12] But miraculously the bullet had missed his carotid artery and spine, so he was able to recover.

His next field of action was the Battle of Fredericksburg, but two days before the fighting began, he was sidelined with dysentery. For someone with fierce pride and unbridled ambition, this was humiliating. In reality, his ego should have been the least of his concerns since dysentery was responsible for more than one in ten deaths during the war. But again, he pulled through.[13]

Many of his comrades wounded at Fredericksburg were now in Louisa’s care, and that of the other nurses at the Union Hotel Hospital. Some had not survived their journey north, while the stench, soiled bandages and cries for help of those still alive overwhelmed the senses.

Louisa’s first task was to wash them from top to bottom—literally. She was ordered to command the men to disrobe so the task could be performed properly. Such intimacy with a member of the opposite sex was totally foreign to her New England sensibilities. But she did as instructed, though she could never bring herself to describe the experience.[14]

One new arrival—a soldier by the name of John—caught her fancy, a first for a woman who generally had a poor opinion of the men around her. She mustered the courage to befriend him. Though he was a man of few words, he welcomed her overtures, much to her delight. But the relationship was short-lived. John’s wounds were fatal.

Louisa was with him on the day he died. She saw tears on his cheeks as his pain and the prospect of dying engulfed him. Encircling him with her arms she said, “Let me help you bear it, John.”[15]

Louisa recorded this and many other experiences at the hospital in letters to her family. When she returned to Concord after her service, she was urged by a family friend—who also happened to be the owner of a prominent local magazine—to submit them for publication. Though she didn’t see the appeal of her reminisces, she dutifully edited her stories and fictionalized them for literary effect.

Louisa May Alcott (1862)

Hospital Sketches—the name of her collection—was a triumph, receiving praise from such luminaries as Henry James, Sr. At long last, Louisa May Alcott had found her voice. Had she not borne witness to the suffering and courage of the men in her care, it is unlikely that Little Women would have ever been written—a book that not only cemented her reputation as a gifted writer but also demonstrated that those who write for children can be taken seriously.[16]

Alcott enjoyed much success after Little Women, receiving critical acclaim for many of her other books, including Eight Cousins and An Old Fashioned Girl. But on March 1, 1888 she was abruptly summoned to her dying father’s bedside. That same day, she penned a letter to a friend saying, “[A]s I don’t live for myself I hold on for others, & shall find time to die some day, I hope.”[17] Later that day, she experienced a headache. She decided to rest, but never opened her eyes again. She passed two days later, while her father was being interred.

Wendell, however, did not think highly of Hospital Sketches or Alcott’s other work. Speaking at his alma mater many years after the war, he decried society’s endless pleasure seeking and its desire to be sheltered from the struggles of life. A culture of pity and sympathy, he believed, has no place in the world. “If it is our business to fight, the book for the army is a war-song, not a hospital-sketch.”[18]

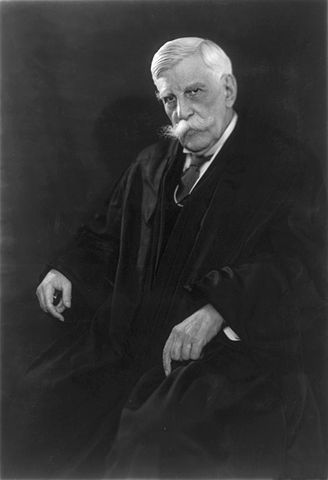

Having been severely wounded a third time at Chancellorsville and then witnessing the horror and depravity of the Wilderness Campaign, the worldview of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. should come as no surprise. While Alcott chose to respond to the wounds of war with compassion and found in life’s struggles the materials to build a better society, Holmes relied instead on the transcendent virtues of duty, fortitude and bravery to conquer adversity—running to the fight, not away from it. In the words of one essayist, he was “a Yankee, strayed from Olympus.” But, as astutely noted by the author John Matteson, strong emotions—the very thing he faulted in the works of Alcott—were also at the core of Holmes’ beliefs.[19] And both of them were troubled by society’s obsession with material gain and comfort.

The Civil War had a profound impact on Holmes’ career as an Associate Justice on the United States Supreme Court. “The life of the law is experience, not logic,” he declared. And his wartime experiences convinced him that power and force were the defining characteristics of human relations, not charity and kindness. He believed, however, that the authority of the law could be used to restrain abuses of power, a position he advanced without becoming a partisan ideologue.

After seeing the horrific consequences of atrocious generalship, he no longer showed deference to authority. He was driven not by his own vision but by a profound understanding of the inherent weakness and fallibility of all human beings—including himself. As a result, the lodestar of his jurisprudence, as Matteson notes, was “a willingness to question one’s own thought.”[20]

Astonishingly, Holmes lived another 70 years after the Civil War. When he died in early 1935, he chose not to be buried among the Brahmins in Boston but in Arlington Cemetery, surrounded by those who had fought in the war that defined and shaped him.

Discovered hanging in his closet after his death were two blue uniforms with a note that read, “These uniforms were worn by me in the Civil War and the stains upon them are my blood.” And in his safe deposit box were two musket balls extracted from wounds he suffered during the war.

Undeterred by the wind, sleet and rain, President Roosevelt and many others gathered in Arlington Cemetery to witness the burial of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. and pay their respects. Also in attendance was Holmes’ loyal caretaker, Mary Donellan. When a gentleman told her he was sorry bad weather had marred the ceremony, she smiled and said, “Soldiers don’t mind the rain.”[21]

[1] John Matteson, A Worse Place Than Hell, (W.W. Norton & Company: New York, 2021), p. 147.

[2] Ibid, p. 137.

[3] Ibid, p. 150.

[4] Ibid.

[5] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, (Oxford University Press: New York, 1988), pp. 571-74.

[6] A Worse Place, p. 266.

[7] Catherine Dinker Bowen, Yankee from Olympus, (Little, Brown & Company: Boston, 1944), p. 186.

[8] Battle Cry, p. 574.

[9] A Worse Place, p. 10.

[10] A Yankee, p. 155.

[11] Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red, (Ticknor & Fields: New Haven, Connecticut, 1983), p. xi.

[12] A Worse Place, p. 31.

[13] Ibid, p. 210.

[14] Ibid, p. 284.

[15] Ibid, p. 289.

[16] Ibid, p. 423.

[17] Ibid, p. 426.

[18] Ibid, p. 407.

[19] Ibid, pp. 407-408.

[20] Ibid, p. 421.

[21] Ibid, p. 434.

Great stories. Thanks.

Being somewhat of a Lincoln and Civil War buff, I enjoyed this story tremendously.

Thanks so much!

Jon Blackman

Dick & Jon, I’m glad you both enjoyed the essay. It was fun putting it together. Having been born and raised in the Land of Lincoln, I can never get enough of our 16th President and his leadership during the Civil War. And the lives of Alcott and Holmes were quite extraordinary. Their influence is still being felt today.

Having been raised in Illinois, I too identify with Lincoln and the north of the civil war. Great stories,

thank you very much

You are quite welcome, Brian. And your opinion of my musings carries added weight simply by reason of where you grew up. 🙂

This is good. I particularly like the contrasting of Alcott’s and Holmes’ radically differing mindsets, without any forced attempt to elevate one above the other.

Just this morning, my wife forwarded me a column by historian Heather Cox Richardson (who has developed quite a following) about the role of the state of Maine and its citizens in the run-up to the Civil War and in the War itself. She has this paragraph about the founding of the Republican Party, which references another famous writer:

“Israel and Elihu [Washburn] were both serving in Congress in 1854 when Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act overturning the Missouri Compromise and permitting the spread of slavery to the West. Furious, Israel called a meeting of 30 congressmen in May to figure out how they could come together to stand against the Slave Power that had commandeered the government to spread the South’s system of human enslavement. They met in the rooms of Representative Edward Dickinson, of Massachusetts– whose talented daughter Emily was already writing poems– and while they came to the meeting from all different political parties, they left with one sole principle: to stop the Slave Power that was turning the government into an oligarchy.”

I’d love to hear more about how Emily interacted with those who were instrumental in the fight to make America free.

Loved learning more in depth about her life in “Marmee & Louisa: The Untold Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Mother” by Eve La Planta. I have also visited her home in Concord. The Alcotts were an interesting family. She and her mother both went through a lot and Bronson wasn’t much of a help. Louisa’s writing changed America and helped give a voice to women.

You’re right, Karen. Her writing has had a profound impact on the country, especially young women. The terrible irony of it all is that, but for the Civil War, she likely would not have matured as writer or produced so many fine works of literature.

“ I particularly like the contrasting of Alcott’s and Holmes’ radically differing mindsets, without any forced attempt to elevate one above the other.” You divined and perfectly described my primary objective in writing this essay, Doug.

I tracked down the Cox Richardson piece you referenced from the Moyers’ site, which I quite enjoyed. I was unfamiliar with that particular historical episode, and it dovetails nicely with my essay. I have not read any of Richardson’s books but I just took a step towards remedying that oversight by ordering “How the South Won the Civil War.”