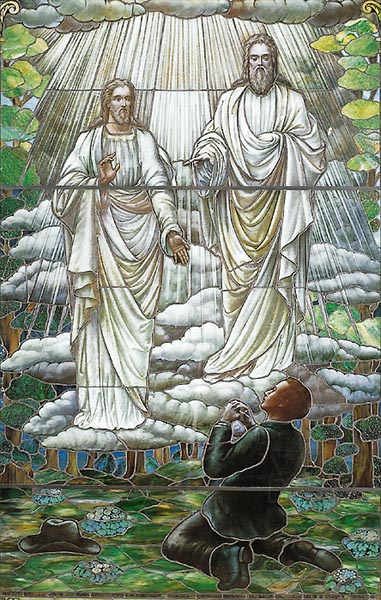

While every member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is acquainted with the First Vision, few are familiar with its history. By “history” I mean the role it has played in defining the mission and theology of the church. And like most history, it’s a bit messy.

In the spring of 1820, a few days after Joseph Smith had sought answers from God in the Sacred Grove regarding his personal salvation, he shared his experience with a local Methodist preacher who treated him with contempt, saying that it was all of the devil and that such things as visions and revelations had ceased with the apostles of old. Not surprisingly, this rebuke by a prominent minister had a profound impact on the boy. He turned inward in an effort to reconcile what he had been told by this man of the cloth and what he had experienced—so much so that, according to the historical record, he didn’t tell anyone else about his vision for at least a decade. He chose to keep silent rather than subject himself to further ridicule.[1]

A revelation he received in April 1830 instructed him to record the events that made him a prophet, but he was slow to heed its counsel. It was not until 1832—12 years after the event—that he produced the first written account of the First Vision. But over the next ten years he provided several additional versions as he became more open about sharing this intimate experience.

Notwithstanding his willingness to now discuss this heavenly manifestation, the First Vision was not common knowledge, even among the members, in the early years of the church.[2] It did have its champions, such as Franklin D. Richards, head of the British Mission, and Orson Pratt, the person who coined the term “First Vision”in 1849.[3] But they were the exceptions that proved the rule. It was not canonized until 1880,[4] and the first time it was employed to teach the LDS doctrine of the Godhead was 1883, and then only obliquely.[5]

All of this began to change in the early 20th century. The story was first used in Sunday school texts in 1905, in priesthood manuals in 1909, in a separate missionary tract in 1910, and in histories of the church three years later. And in 1916, the church acquired ownership of the Smith family farm in Palmyra, New York, to preserve the site where the First Vision was believed to have occurred.

By 1950, Joseph’s account of his theophany was denominated “The Joseph Smith Story.” Eventually, as noted by Mormon scholar Kathleen Flake, “it would be granted the status of the beginning point, the fountainhead, of the restoration of the gospel in this dispensation.”[6]

So why did this happen? What was the catalyst for this momentous shift in LDS theology? The answer is rather prosaic: an apostle decided he wanted to get involved in national politics.

In 1902, Elder Reed Smoot sought the prophet’s permission to run for the United States Senate. Though such a request by an apostle was unprecedented, his timing, as it turns out, was most auspicious.

President Joseph F. Smith had begun to realize that there was no future in the self-isolation practiced by the Saints in the second half of the nineteenth century. Hiding behind the Rocky Mountains was inconsistent with taking the message of the gospel to the four corners of the earth and was an impediment to the church’s acceptance by modern society. Sending Brother Smoot to Washington, Smith believed, would be an excellent way of letting the world know that the church wished to engage with “gentiles.”

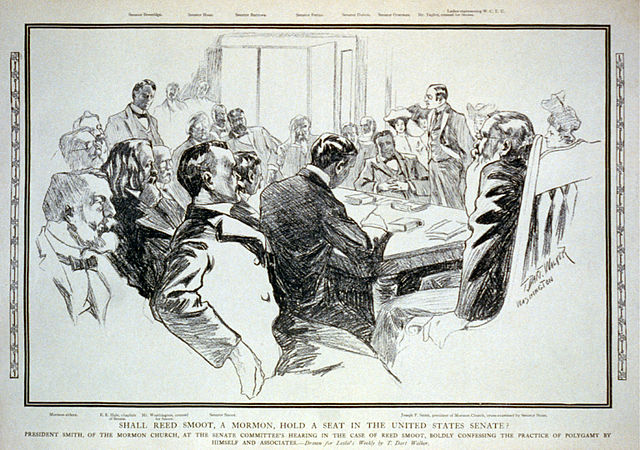

Not surprisingly, Smoot handily won the election and took his seat in the United States Senate in 1903. He soon discovered, however, that many of his colleagues did not want him there—so much so that they sought to expel him, something that can be done at any time by a two-thirds vote of the Senate.

The following year, expulsion hearings began before the Committee on Privileges and Elections. Smoot was charged with: (1) having taken a religious oath that required his first allegiance be to his church, not the Constitution and laws of the land, and (2) leading a faith that continued to engage in polygamy even though it had foresworn the practice in 1890 when Wilford Woodruff issued the First Manifesto.

This did not come as a complete surprise to Smoot since, just four years before, B.H. Roberts, a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy, had been denied his seat in Congress because he was a polygamist. But Smoot was a monogamist and opposed plural marriage.

President Smith (along with many others) was summoned by the committee to respond to these two allegations. His testimony lasted six days and it was grueling.

On the first question, Smith found it difficult to rationalize convincingly the subordination of prophecy to democracy without undermining the church’s strict hierarchal order. He tried to finesse this by quoting the Doctrine and Covenants: “Let no man break the laws of the land, for he that keepeth the laws of God hath no need to break the laws of the land.”[7] But Smith had previously declared in a General Conference that this injunction had no application to the Edmunds Act, the federal statute outlawing polygamy, since it violated the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious freedom.[8] And the fact that polygamy was still being practiced belied his assurances to the committee.

On the issue of post-manifesto polygamy he struggled even more. He, along with several other apostles, had actually sanctified several of these unions after 1890. Indeed, two of the sitting members of the Quorum of the Twelve—Elders John W. Taylor and Matthias Cowley—continued to engage in the practice and thumbed their noses at the summonses they received from the U.S. Senate.

What Smith provided in response to the Committee’s inquiries on plural marriage was a carefully worded statement that no such unions had been approved “with the sanction, consent, or knowledge of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”[9] As Stephen C. Harper, Professor of Church History and Doctrine at BYU, notes, the prophet “hoped that by prevaricating he could deflect the demands that the saints pay a price or take a punishment for their post-manifesto polygamy.”[10] But the ten witnesses who followed him—one of whom testified that an apostle had performed her plural marriage—contradicted his testimony and proved more credible.[11] Thus, Smith failed to convince the committee that the church had renounced plural marriage. He knew further action on his part was required or else Smoot would be expelled.

One month later, Smith issued the “Second Manifesto,” reiterating President Woodruff’s earlier proclamation. The prophet categorically prohibited all plural marriages and threatened all who engage in it with immediate excommunication. In other words, “This time, we really mean it!”

Reed Smoot’s reports from Washington, however, were not encouraging. The Second Manifesto had been received with considerable skepticism; and, it wasn’t just his Senate seat that was at risk. Legislation was now being considered that directly targeted the church; and the brazen conduct of Taylor and Cowley was only fueling the fires of opposition. Smoot was so infuriated by the behavior of his fellow apostles that he refused to sustain them during the October 1905 General Conference.[12]

Matthias F. Cowley

John W. Taylor

The Quorum of the Twelve was deeply divided over who should be sacrificed: Smoot or Taylor and Cowley. But prior to General Conference, pressure began to mount on the two recalcitrants to resign from the Quorum of the Twelve, something they were finally compelled to do on October 28, 1905. The priesthood of each man was suspended and Taylor was subsequently excommunicated for his continued opposition to the church’s stance on polygamy.

While these steps mollified several of the church’s detractors in Washington, they were terribly disorienting for many members of the church for whom theocracy, economic communalism, millennialism, and, above all, polygamy, had been the foundation of their faith. President Smith realized that, having razed that theological substructure, he had to replace it with something new. He began that process by looking to the east, to the church’s origins.

Earlier that year, he had commissioned the construction of a monument in South Royalton, Vermont, the birthplace of Joseph Smith, to honor the founder of the faith. It was serendipitous that the centennial of the prophet’s birth—December 23, 1905—occurred when the Saints desperately needed something to celebrate.

Five days before the commemoration, President Joseph F. Smith gathered what was left of the senior leadership of the church and boarded a train for Vermont. They arrived at their destination on the 22nd and were joined by many Saints from New York and Boston for the dedication the following day.

In his dedicatory prayer, President Smith made an offering of each element of the monument: (1) the cement foundation represented the primitive church with apostles and prophets, and with Christ as the cornerstone; (2) the 30-ton base typified the rock of revelation; and (3) the 38.5-foot shaft of granite represented Joseph Smith himself—one foot for each year of his life—and the revelatory power and divine authority bestowed upon his successors. And on the north face of the monument was a prominent reference to the First Vision.[13]

Afterwards, Joseph F. Smith became emotional and overcome with joy. His mind was flooded with competing thoughts—knowing that he was standing on the same ground as his ancestors, but also remembering when he was an adolescent and his father, Hyrum, and the prophet, bounced him on their knees shortly before they departed for the jail in Carthage. These feelings further reinforced his belief that the church needed to renew its commitment to its first principles.[14]

The church’s emphasis on the restoration of polygamy, the institution of a theocratic government, a communal economy and the gathering of Israel had obscured the Christian core at the center of Mormonism.[15] Smith began the requisite course correction by raising the profile of “Joseph Smith’s first vision and its position as the beginning of the Saints’ narrative.”[16] He spearheaded the effort to replace polygamy—one of Joseph’s last revelations—with his first, with a renewed emphasis on the Lord Jesus Christ.

This initiative commenced on their return trip where they stopped at Palmyra and sang the hymn “Joseph Smith’s First Prayer” in the Sacred Grove.

And, as he visited various congregations, President Smith instructed the youth by calling on a fourteen-year-old boy to stand and play the part of the prophet as he narrated the story of the First Vision.[17]

President Smith’s actions redounded to the benefit of Reed Smoot. While the Committee on Privileges and Elections voted 7-5 to expel him, the full body of the Senate voted overwhelmingly not to, 43-27 in Senator Smoot’s favor.

Arguably the most transformative president of the church in the 20th century, Joseph F. Smith, in the words of LDS scholar, Kathleen Flake, “signaled the church’s intent to come out from behind its mountain barrier and claim a place in America at large. Whereas Smoot’s election constituted a claim to participation in America’s future, the Joseph Smith monument staked a claim to America’s past. For the saints, the dedicatory ceremonies in Vermont marked an attempt at homecoming and healing.”

As the Apostle Richard Lyman declared at the conclusion of the proceedings: “And now we come back. The west and east meet here…. We want your friendship; you have ours.”[18]

[1] Steven C. Harper, First Vision: Memory and Mormon Origins, (Oxford University Press: New York, 2019), pp.9-11, 51. Joseph shared with his father the details of his first visit from the Angel Moroni in 1823, but there is no evidence in the journals of any family member or any other source that he discussed the First Vision with anyone until 1830, save a lone Methodist minister.

[2] Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity, (University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 2004), p. 118; James B. Allen, “The Significance of Joseph Smith’s ‘First Vision’ in Mormon Thought,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Vol. 1. No. 3 (1966), p. 37.

[3] Harper, First Vision, pp. 73, 77.

[4] Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity, p. 121.

[5] Allen, “‘First Vision’ in Mormon Thought,” p. 38.

[6] Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity, p. 118.

[7] D&C 58:21-22.

[8] Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity, pp. 79-80.

[9] Harper, First Vision, p. 130.

[10] Ibid, pp. 115-117.

[11] Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity, pp. 80-81.

[12] Ibid, pp. 93-94, 99-100.

[13] Harper, First Vision pp. 132-133.

[14] Harper, First Vision, p. 133.

[15] John G. Turner, The Mormon Jesus: A Biography, (Belknap Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2016), p. 293.

[16] Steven C. Harper, “Raising the Stakes: How Joseph Smith’s First Vision Became All or Nothing,” BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 59, No. 2, 2020, p. 30.

[17] Ibid, p. 33.

[18] Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity, p. 114.

Interesting and informative. I knew the history quite well but had never put the Smoot issue into context. I know the early Church missionaries to England didn’t teach the first vision. Somehow these facts and inconsistencies between the different versions don’t bother me since I know we are working with out finite lives to relate a profoundly decisive and enlightening moment. I literally feel it in my soul. That being said the events around the movement away from polygamy are interesting and difficult. My grandmother (a daughter of polygamy) lived through it. My mom remembers the two wives living together in SLC and doing temple work after my great grandfather’s death. They all had such strong testimonies it inspires me and helps me find a place in the world through the heritage of my family.