Set forth below is the text of a talk I gave on Mother’s Day, May 8, 2022, in the Sacrament Meeting of the Arlington First Ward, Arlington, Virginia.

When Margaret was expecting our first child, a colleague of mine asked whether we were planning on a natural, drug-free birth. That was our original intent, I told him, until I learned she wanted me by her side in the delivery room. There was no way I could endure the ordeal of child birth without a couple of really stiff drinks and a valium. [Pause till laughter subsides.]

As much as Margaret would love to be the subject of my talk, I have been asked to speak on women in the Old Testament. This is a vast topic about which many books have been written, so I will focus my remarks on the way women in general were regarded in the Hebrew Bible, and on experiences in the lives of a few of them.

To say that the ancient world was hierarchal and patriarchal is to state the obvious. Women had few legal privileges or institutional responsibilities in either the civic or religious arena. They were subservient to men, and their sphere of influence was largely confined to the home.[1] In the words of the Psalmist, “Your wife shall be like a fruitful vine within your house ….”[2]

But here’s the thing. While men in our modern world—including, regrettably, some leaders of our church[3]—have employed unflattering stereotypes, made condescending remarks, and voiced derogatory opinions when discussing the intellect and abilities of women, the Old Testament is devoid of such insults,[4] save a lone verse in Ecclesiastes.[5] To the contrary, the Hebrew Bible is replete with inspiring stories about women, many of which portray the female protagonist as a resourceful adversary or worthy partner; but never as man’s inferior.[6]

There are two likely explanations for this incongruity. Male dominated societies were the norm in the Near East, predating the Israelites by 1,500 years. As a result, society’s structure is never discussed in the Old Testament—but nor is it defended, since the possibility of social change for the better is integral to biblical thought.[7] Second, portraying women as powerless and subordinate while being man’s equal spiritually and intellectually allowed Israel to make sense of a world where it was subordinate to the power and authority of the dominant nations surrounding it.[8]

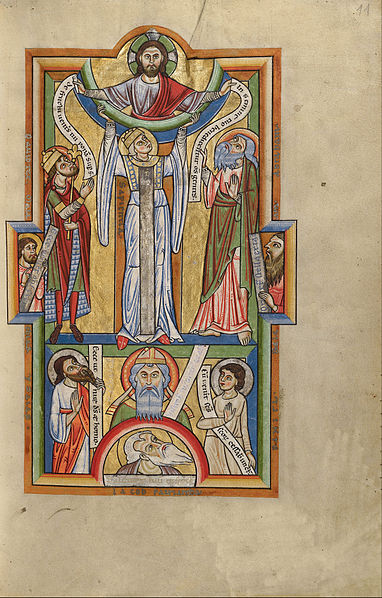

Although women were not considered deficient or lacking, they were most certainly viewed as different, sometimes in mystical ways. For example, they functioned at times as oracles, a role often performed by women in ancient times. Just as the Oracle at Delphi was the means by which the Greeks believed their gods spoke to them, women in the Old Testament were sometimes the vehicle through which the Lord’s will was made known.[9]

For example, when Abraham exhibited reluctance to ask Hagar and Ishmael to leave his household as he had been commanded, God admonished him to listen to his wife: “hearken unto [Sarah]; for in Isaac shall thy seed be called.”[10]

The role of Isaac’s wife, Rebecca, as a mouthpiece for the Lord was even more explicit when she received an oracle about the destiny of the twins she was carrying: Esau and Jacob.[11] But the message from Jehovah was ambiguous regarding which child should receive the birthright. It was left to Rebecca to divine its meaning, which she did.

The respect accorded to Sarah, Rebecca and other women in the Old Testament can be understood, in part, as the product of cultural factors. While scholarly pursuits and societal leadership roles were off limits, their sophisticated technical skills—turning grain into bread, wool into cloth, herbs into medicine—combined with their lasting impact on the psyche of the children they reared and taught, gave them a certain gravitas.[12]

They were considered repositories of “wisdom,” grammatically a feminine noun in both ancient Hebrew and Greek.[13] Indeed, the Book of Proverbs speaks of Lady Wisdom as a separate being created by God[14] who appears to have played a role in the creation.[15] She appeals to mankind’s desire to learn, better themselves, and pursue the truth.[16]

One of my favorite women in the Old Testament is a person who is simply known as the Wise Woman of Tekoa.[17]She is recruited by Joab, one of King David’s advisors, to mend a rift between the King and his son, Absalom. David is distraught over the recent passing of his son, Amnon, but is angry with Absalom who was complicit in his brother’s death. Joab has devised a plan to reunite father and son, but he needs a shrewd woman to execute it.

The Wise Woman of Tekoa, with Joab’s help, secures an audience with the king and arrives as a woman in mourning. David is presented with an imaginary problem that mirrors his own family struggles though he doesn’t make the connection. Specifically, she tells the tale of her two sons who were quite close, but one day one rose up and slew the other. Her relatives were furious, insisting she surrender her surviving son for punishment under the law. The woman pleaded with the king to protect not only her son but also the lineage of her husband whose name would not survive in Israel if the boy were executed.

When David seems reluctant to ignore the demands of the law, she replies: “O king, the iniquity be on me, and on my father’s house: and the king and his throne be guiltless.”[18] Upon hearing this, David grants her request. Her son will be spared.

But then, with almost reckless impertinence, she accuses the King of not extending the same mercy to his son Absalom, whom he has ostracized. She then employs a beautiful metaphor to drive her point home: “We must all die; we are like water spilt on the ground, which cannot be gathered up again. But God will not take away life, and he devises means so that the banished will not remain an outcast.”[19] This imagery, combined with her willingness to suffer the consequences if David’s grant of clemency proves to be in error, evoke thoughts of the Savior’s willingness to bear the burden for our mistakes and his godly power to atone for them by gathering together all the water we spill during our lives.

This story, and several others like it in the Old Testament, arguably validate one female stereotype: that of the wily woman. For example, Isaac’s wife, Rebecca, employs deception to secure the birthright blessing for Jacob instead of Esau, her first born.

Ruth likewise aggressively pursues Boaz until he consents to marry her—no small feat given her Moabite ancestry, which made her a member of one of Israel’s most reviled enemies.[20] But the Bible rarely condemns such behavior. To the contrary, in the biblical world, cunning and guile are admirable traits in the powerless, ones often essential to their survival.[21]

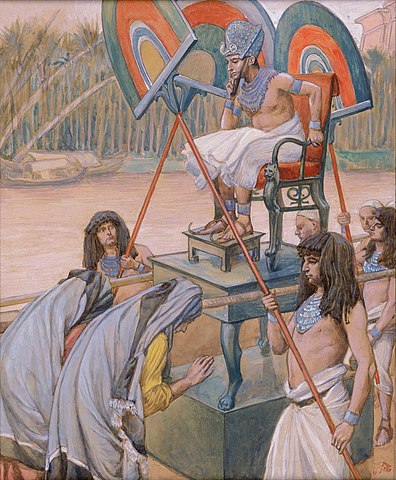

Arguably, the most important role played by women in ancient Israel was that of agents of social transformation. Not only were they charged with preparing children for adulthood, they also were the portals through which all mankind came to earth, both in their capacity as mothers and midwives. Interestingly, among the female metaphors used in the Old Testament for “God as Creator” are: “God as a Mother,” and “God as a Midwife.”[22]

In addition, by ministering to the terminally ill, women negotiated the boundary between this world and the afterlife, easing the transition for those in their care. Women were separated from men after childbirth, during menstruation, and when they cared for the dying, not just because they were ritually unclean; rather, there was something otherworldly about these events men believed they were incapable of comprehending.[23]

The first hint of woman’s unique connection with the divine can be found in the story of Adam and Eve. When the serpent tempts her with the forbidden fruit, Eve’s response contains a Freudian slip we usually miss. While the tree before her is the one of knowledge of good evil, she says the Lord has barred Adam and her from partaking “of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden.” Only the Tree of Life is “in the midst of the garden.”

It’s as if, while she is reaching for the fruit of one tree, her subconscious is thinking of the tree that offers what she covets most: immortality.[24] In one sense, her transgression allows her to achieve that goal: as the Mother of all Living, she and her female offspring possess the godlike capacity to create human beings.

In many ways my mother, who passed away twelve years ago, reminds me of the women of the Old Testament. She had a powerful intellect and a gift for writing, earning a degree in journalism at the University of Illinois. This was quite rare for a woman in her day. Just as Ruth converted to Judaism, she joined the church after she married my father—but only after she acquired a testimony of her own. She not only raised four recalcitrant boys, but also served as a room parent in the local grade school for many years. In addition, she was a dedicated hospice worker for more than a decade. Some of the widows and widowers who witnessed my mother ferry their spouses across the river attended her funeral, which touched me deeply.

As an angel of the Lord, my mother has spoken to me on two occasions from beyond the grave. One of those experiences I have never shared with anyone before, except Margaret. But I will today.

Ten years ago, while we were on a short vacation, I had a dream where I found myself seated on a bench on the grounds of the Washington Temple. My mother was next to me and we sat in silence for a while. Suddenly, she threw her arms around me, began to cry, and said, “hold me.” I enveloped her small, frail body in my arms, whereupon I awoke with tears streaming down my face.

Reflecting upon this experience I realized her sadness was the result of my failure to ensure that her parents had been sealed, as husband and wife, in the temple. Margaret and I quickly rectified that oversight, serving as proxies in the celestial marriage of my maternal grandparents.

The German author and screenwriter, Werner Herzog, once said: “Eternity depends on whether people are willing to take care of something.”[25] No one, in my opinion, had a better understanding of what is of eternal value and why those things require our constant care and attention than the women of the Old Testament—and my mom. Of this I testify, in the name of Jesus Christ: our Savior, Lord and Master. Amen.

[1] Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative, 2nd Ed., (New York, New York: Basic Books, 2011), p. 181.

[2] Psalms 128:3 (JPS Tanakh).

[3] E.g., (1) “If it is the duty of a husband to take a wife, take her. But it is not the privilege of a woman to dictate the husband, and tell who or how many he shall take, or what he shall do with them when he gets them, but it is the duty of the woman to submit cheerfully. Says she—’My husband does not know how to conduct himself, he lacks wisdom—he does not know how to treat two wives and be just.’ That all may be true, but it is not her prerogative to correct the evil, she must bear that;…” – Brigham Young, , Journal of Discourses, vol. 17, no. 8 (May 7, 1874). (2) “Women were never placed to lead. * * * Women are made to be led, counseled, and directed.” – Heber C. Kimball, Journal of Discourses, vol. 5, no. 7 (July 12, 1857. (3) “[W]oman’s primary place is in the home, where she is to rear children and abide by the righteous counsel of her husband. Peter counseled: ‘Ye wives, be in subjection to your own husbands,” wearing simple unadorned apparel.’” – Bruce R. McConkie, Mormon Doctrine, (Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, Inc., 1958), p. 764. (4) If women were to receive the priesthood, “the male would be so far below the female in power and influence that there would be little or no purpose for his existence…. [He] would probably be eaten by the female as is the case with the black widow Spider.” – Hartman Rector, Jr., letter to Mrs. Teddie Wood, a member of Mormons for the Equal Rights Amendment, as quoted in Women in Authority, ed. Maxine Hanks, (Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature books, 1992), p. 119

[4] Tikva Frymer-Kensky, Reading the Women of the Bible: A New Interpretation of Their Stories, (New York New York: Schocken Books, 2002), p. xvi (“[T]he Bible … does not claim that women need to be controlled because they are wild, or need to be led because they are foolish, or need to be directed because they are passive, or any of the other justifications for male domination that have been prevalent in Western culture.”)

[5] Ecclesiastes 7:26.

[6] Biblical Narrative, p. 182. See also Reading the Women, p. xvi.

[8] Ibid, pp. xvi-xvii.

[9] Ibid, p. 327.

[10] Genesis 21:12.

[11] Genesis 25:23.

[12] Reading Women, p. 329.

[13] Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler, The Bible With and Without Jesus, (New York, New York: HarperOne, 2020), p. 83.

[14] Proverbs 8:22-23,30-31.

[15] Roland E. Murphy, “Wisdom and Creation,” Journal of Biblical Literature 104 (1985); pp. 3-11 (8). (“There can be no doubt about [Lady Wisdom’s] divine, origin, and it is certain that she is somehow associated with creation. Indeed, a specific role in the created is clearly stated” in Proverbs 8:31.

[16] Steven L. McKenzie, How to Read the Bible,(New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 97.

[17] 2 Samuel 14:1-17.

[18] 2 Samuel 14:9.

[19] 2 Samuel 14:14 (ESV).

[20] Irene Nowell, Women in the Old Testament, (Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1997), pp. 91-92.

[21] Reading the Women, p. 19.

[22] Hosea 11:3-4; Isaiah 45:10-11; Psalms 22:11. Two midwives, Shiphrah and Puah, played an important role in the birth of Moses. Their willingness to defy the Pharoah’s edict to drown all Hebrew newborns saved the lives of the prophet and other male infants. See Women in the New Testament, pp. 47-48,

[23] Ibid, p. 329.

[24] Subversive Sequels, p.104.

[25] Quoted in The Prague Sonata, by Bradford Morrow, p. 341 (Atlantic Monthly Press Oct. 3, 2017).

Josh Hartshorn invited us all to read this talk today and we have enjoyed it. I would encourage you to keep writing and sharing. Thank you!

Great talk. Some of these insights regarding the essential nature and divinity of women remind me of the book I’m currently reading, “The Truth and Beauty” by Andrew Klavan. I highly recommend it.

Thanks so much for your encouragement, Ann. And I’m glad you enjoyed it.

My only disappointment when I gave it was the failure of the congregation to laugh a bit louder at the joke I told at the beginning. But maybe it was my delivery …

Thanks for your kind words, Grant, and more importantly, for the book recommendation. I had missed Klavan’s book, but I just corrected that oversight. Anxious to read it.

Touching and as usual insightful.

thanks for sharing. I hear from my husband quite often but my favorite was just after my broken femur when Mindy, my daughter had a dream and saw her dad. He had one message, “take care of your MOM”

I also used the priesthood power I share to ask for his release from this world.