While en route to Jerusalem for the last time in his life, Jesus is approached by a rich young man who asks him the following question: “Teacher, what good deed must I do to have eternal life?” The Savior’s response is both clear and concise. “If you wish to enter into life, keep the commandments.”[1]

In Washington, there is a sage piece of advice given to constituents who ask their Senator for a favor: If he says ‘yes,’ the only thing else you should say is, “Thank you, Senator; we really appreciate your help; goodbye.” You don’t linger or say anything more lest you cause him to reconsider or qualify his promise.

This idea never occurred to Christ’s interlocutor, so he asked another question, “I have kept all [the commandments], what do I still lack?” Christ’s response was not to his liking. If he wished to be perfect, he was told, he must sell all his possessions, give the proceeds to the poor, and then become one of Jesus’ disciples. The young man was deeply saddened by this response, for his attachment to his possessions was great.[2]

Some believe the Savior intended his counsel for all people of means, not just this fellow. But the text clearly does not support such a conclusion. Whenever Christ interacts with an individual, he is always cognizant of his unique circumstances. Jesus was addressing the spiritual needs of this one man, who we can surmise is single with no dependents. While Christ used this encounter to underscore how difficult it is for the wealthy to enter God’s kingdom, Matthew, later in his gospel, mentions a loyal disciple by the name of Joseph of Arimathea, who is a “rich man.”[3]

Because we focus almost exclusively on the question of wealth, I believe we miss much of what Christ was trying to convey.

First, we overlook the fact that Christ is not reneging on his original promise to the young man: “If you keep the commandments, you will have eternal life.” In other words, if you stick to the “checklist gospel” (go to church, be honest in your dealings with others, help the poor, etc.), eternal life is guaranteed.

Second, we fail to consider why this young man was not content with the response to his first question. A lot of folks would have simply ticked off the final item on their checklist and walked away happy. But that’s the whole point of the story.

Living forever simply was not enough for him. Stated differently, when he asked, “What do I still lack?” he wasn’t saying, “What have I overlooked?” Rather, he was saying, “Rabbi, though I have done my best to follow the commandments, why do I feel there is something missing in my life?” When Jesus revealed what it would take for him to find what he was looking for, he instantly grasped the truth of his words but was “grieved” because the price was too steep.

There is no shortage of people who believe they know what we need to fill the void in our lives. And should we tell them there is no void that needs filling, they will often try to disabuse us of that notion.

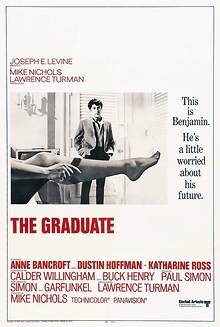

My first encounter with this phenomenon was in 1967 when, at the age of 14, I saw the “The Graduate,” a satirical dramatic comedy about a young man, Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman), who is trying to figure out what to do with his life. At his college graduation party, a friend of his father, Mr. McGuire, accosts him and asks to speak in private.

Once they are alone he says, “Ben, I just want to say one word to you. One word. Plastics.” Ben, not knowing what he means, quizzically repeats the word, whereupon McGuire says, “There’s a great future in plastics,” and walks away. He has baited the hook, hoping Ben will believe this is a smart career move and that he’d be a fool not to seize this opportunity.

C. S. Lewis, in one of his most memorable lectures, “The Inner Ring,”[4] describes situations such as these as an invitation by an insider to someone on the outside to join the exclusive ranks of those “in the know.” If Ben accepts Mr. McGuire’s invitation, he will soon discover that there are multiple “Inner Rings” within the ring he just joined, each smaller—and more exclusive—than the one he just entered. As Lewis notes, for many “the desire to be inside the local Ring and the terror of being left outside” governs their lives.[5]

Being on the inside, having access to information and relationships denied to others, gives us a “delicious sense of secret intimacy.” But to attain this status, we are often asked to make compromises.

At first, they may seem innocuous. Your boss invites you to join a special committee for a critical project, though it will mean working weekends and cancelling a family vacation you had planned. But as you advance from one Inner Ring to the next, at some point you will likely be asked to make even greater compromises, some of an ethical nature. Will you draw the line at that point, or has your desire to be a member of the sanctum sanctorum grown so strong that you cannot bear the thought of expulsion?

Not everyone who seeks membership in an organization or group with a finite number of members is beguiled by the Inner Ring. Those, for example, who are motivated simply by the sheer pleasure of playing a musical instrument proficiently and who seek membership in an orchestra or admission to Julliard for the purpose of honing their craft, will, if they succeed, become members of an exclusive circle. But if their motive is simply to become better musicians and to be in the company of others with the same desire, they are far less likely to succumb to the temptations of the Inner Ring.

If their aspirations are noble—and this holds true for all professions and occupations—they will experience no feelings of exclusivity or superiority. And if some of their colleagues approach their job with a similar attitude, the group they form, while having the outward appearance of an Inner Ring, will not have as its catalyst fame, fortune, or status. Nor will their members necessarily be promoted to the highest offices. Instead, as Lewis explains, they will be content with doing something they all enjoy and doing it well, for their betterment and in service of others. This bond he calls “friendship,” something ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, such as Plato, Aristotle and Cicero, considered a virtue.[6]

Lewis’s insights, I believe, help inform our understanding of the Savior’s exchange with the young rich man. In Mark’s version of the story, immediately before Jesus tells the man what he is missing, are these words: “Jesus, looking at him, loved him and said….” Christ was drawn to this fellow. He liked him. He thought, “This guy would make a great disciple and a good friend.”

It was their affinity for each other, combined with a genuine love for the work they were doing, that sustained the disciples and, I imagine, even Jesus. They hung out and dined together. I suspect that once in a while they bickered and, I hope, made irreverent remarks and poked fun at each other. (If they didn’t, then I definitely wouldn’t fit in.) And they welcomed newcomers of all stripes.

George Fox, the founder of the Quaker religion, understood this. For the actual name of the faith he founded is the “Religious Society of Friends” (also known as “Friends Church”). Theirs is an interdependent religious community with a highly developed moral understanding. In the 18th century, its English branch campaigned to end the slave trade while the American Friends petitioned Congress in 1790 to abolish slavery.[7] It was decades before other churches followed their example—and Christ’s.

The biblical scholar, Amy-Jill Levine wonders if our young rich man ultimately heeds the Savior’s advice and joins the ranks of the disciples.[8] In Gethsemane, after Mark reports that “all of them had deserted him and fled … a certain young man was following him wearing nothing but a linen cloth.” But when the guards tried to seize him, they managed only to grab hold of his clothing, and he “ran off naked.”[9]

Could this be Christ’s questioner, Professor Levine asks? I hope so.

[1] Matt. 19:16-17 (NRSV)

[2] Matt. 19:20-22 (NRSV)

[3] Matt. 27:57 (NRSV)

[4] C. S. Lewis, “The Inner Ring” in The Weight of Glory, (New York, New York: HaperCollins, 1980), pp. 141-157.

[5] Ibid, p. 146.

[6] Ibid, pp. 156-157.

[7] American Constitutionalism: Volume I: Structures of Government, 2nd ed. (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), Chapter 4, Supplementary Material.

[8] Amy-Jill Levine, The Difficult Words of Jesus: A Beginner’s Guide to His Most Perplexing Teachings, (Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon Press, 2021), p. 30.

[9] Mark 14:50-52 (NRSV).

Interesting piece. The compromises often made by people wanting to be part of the “inner ring” often seem to undercut what they are attempting to achieve and pure accomplishment. There is an interesting question as to how much one must follow and acquiesce to those who are already in positions of status in order to gain their acceptance. Should one put people over principle? While Christ was without sin the purity of others in the inner rings of power is often not as great as one would desire and form over substance reigns.

Karen, I think Christ’s example provides the best answer to the dilemma you describe. Clearly his disciples acted, at times, as if their callings somehow made them better than others. And they also sought to elevate their status in the eyes of their Master, inquiring, “Who among us will the greatest in the kingdom?” Notwithstanding their vanity and the impurity, at times, of their motives, they were good men who made great sacrifices and for an important work.

Naturally, as Lewis taught, we should not pursue membership in an Inner Ring for the wrong reasons. But if we think we can make a difference there, we should, like the Savior, be tolerant of those who pursue membership for different reasons except, perhaps, when they ask us to acquiesce to an action or decision that runs contrary to our most important principles. We should also make allowance for our own blind spots and be willing to admit that no one’s motives—with the exception of Christ—are always pure.