The Past is a Foreign Country: They do things differently there.

L. P. Hartley

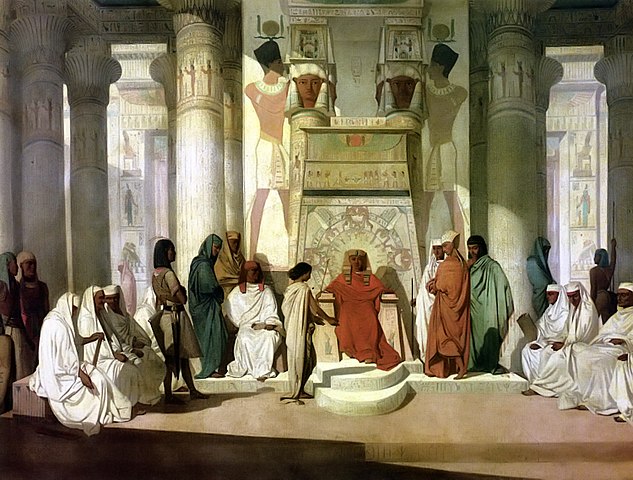

Ever wonder why there were no economists before Adam Smith, the great British philosopher and pioneer of political economy? As odd as this may seem, prior to the 18th century no one had ever conceived of organizing a system around the notion of personal gain. Historically, all commercial and industrial activity—that of the Egyptians, Greeks, Romans and the people of the Middle Ages—was organized in just one of two ways.

The first was tradition, where occupations were passed from one generation to the next according to the accident of birth. You were born to your social task and you were expected to accept it. Religion was frequently invoked to justify this approach. If your lot in life was one of poverty and disease, remember: this brutish and brief mortality is simply a prelude to the sweetness of eternal life.[1]

The second approach was a command economy, where the whip was employed to build the pyramids and the Party Chairman’s five-year plan would ensure that crop yields meet their quotas. Economic survival was achieved by a ruler’s edicts and harsh penalties guaranteed compliance. Like the tradition model, it was fatalistic.[2] In the words of Aristotle: “From the hour of their birth, some are marked by subjection, others for rule.”[3]

Each of these approaches—tradition and authoritarianism—has its roots in a collectivist culture where political, religious and commercial affairs are inseparable and an individual’s identity is defined by the characteristics, values and talents of his community. He lives his life in accordance with the community’s expectations and finds meaning not in his “specialness,” but in the group’s shared interests, history and loyalty.

Families are the raw material of every successful communal society, not individuals. Indeed, they were a critical survival mechanism since, until modern times, protective police forces and social safety nets were unheard of. And by “family” a collectivist means one’s extended family, including aunts, uncles, cousins and all other members of the household, such as servants.[4]

In 1776, however, collectivism found a challenger: individualism. For that was the year Adam Smith published his magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations, where he proposed a revolutionary approach for organizing society’s commercial affairs.

Adam Smith; engraving by John Kay (1790)

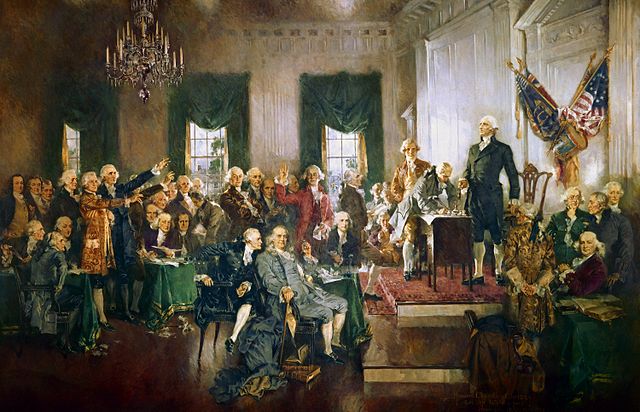

It was also the year of the American Revolution, which ultimately yielded a constitutional system that separated politics from religion and accorded each individual the freedom to organize his economic and personal affairs as he saw fit.

Signing of the Constitution, by H.C. Christy (1940)

First Page of the U.S. Constitution

These were some of the most pivotal events in human history, and are among the chief legacies of the Enlightenment. More to the point, they define those of us who live in the West.

Would we willingly trade places with a laborer or craftsman living in the Ancient Mediterranean or Medieval Europe? No way. But would that laborer or craftsman wish to inhabit our world? I rather doubt it. The pace of our lives is the polar opposite of his, and the speed with which things change in our time would overwhelm him. He would also be perplexed by the number of individuals who live alone and work hundreds of miles away from their family. And how could he comprehend why people, for emotional support, often pay someone called a “therapist”[5]and look for companionship via something called social media?

I am not critiquing our way of life or extolling the virtues of the collectivist alternative. Each has its weaknesses and its strengths. Rather, I’m endeavoring to show how these cultures serve as a prism through which its members perceive and interact with the world.

This is important because our individualist way of life is not the norm—historically or even today. Indeed, according to a study performed by the Dutch social psychologist, Geert Hofstede, highly individualistic countries such as the United States, Great Britain and Australia are the exception, not the rule. The dominant culture in most countries is more akin to ancient and modern Mediterranean communal cultures.[6]

The authors of our ancient scriptural texts all hailed from highly collectivist societies. In the Bible we find the language of collectivism everywhere. Individuals, for example, are often introduced not as stand-alone entities, but as members of a family: “[Mahalath], the daughter of Jerimoth the son of David, … and Abihail the daughter of Eliab the son of Jesse.”[7]

When we ignore the cultural influences in the inspired words the ancients left us and choose, instead, to interpret their words through “individualist eyes,” we frequently miss or distort the teachings the Lord was trying to impart. A prime example is the story of Jacob and his twelve sons, one of whom was a lad named Joseph.[8]

Most Christian faiths, including our own, focus almost exclusively on Joseph in this story. For Americans, it’s a classic rags-to-riches story: young man forced from home, overcomes adversity, and finds success all the while maintaining his integrity. In the words of the Old Testament Institute manual, “Joseph, always seemed to do the right thing; but still more importantly, he did it for the right reason.”[9] But this is not true. Joseph made some serious mistakes, which are readily apparent to someone reared in a collectivist culture. More importantly, Joseph is not the focus of this story.

Everyone in this tale does something wrong, but the biggest knucklehead is Jacob. His repeated flouting of ancient traditions sows the seeds of discord in his family. And this pattern of behavior began well before he had children.

He foolishly asked Laban for Rachel’s hand in marriage before her elder sister, Leah, had found a husband. When Jacob becomes angry after discovering he has been tricked into marrying Leah, Laban has to remind him that, “It is not our custom here to give the younger daughter in marriage before the older one.”[10] Laban could have also added, “Dude, I’m giving you a taste of your own medicine. Have you forgotten how you cheated your brother Esau out of his birthright?”

Jacob continues in this vein when Rachel—who Laban eventually allows him to marry—gives birth to Joseph. The boy is the apple of his father’s eye, which does not sit well with Jacob’s other boys who believe, as is customary, the eldest male should be accorded preferred status. Joseph, for his part, makes a volatile situation worse when he tattles on his older brothers, reporting their misdeeds to their father. Jacob then adds more fuel to the fires of sibling rivalry by rewarding him with a nifty colorful coat and dispatching him to check up on his brothers, who become so incensed they plot to dispose of him.

While competition among brothers in our society rarely leads to thoughts of fratricide, the actions of Jacob and Joseph are considered ominous by the other children and their families. This isn’t simply about who is dad’s favorite. Jacob has clearly designated Joseph his heir, though Joseph is younger than all of his brothers, save Benjamin.

Ordinarily, upon Jacob’s death his firstborn would assume the role of family patriarch and the responsibility of caring for all other family members. But Jacob manufactures a loophole to the hallowed tradition of primogeniture: Joseph, while not technically the oldest, is the firstborn of his favorite wife, Rachel.

The rest of the family feels threatened by this decision since Joseph has already made clear his attitude towards them: “Let me tell you about this dream I had which reveals y’all will someday bow down and worship me.” Since he believes his dream came from God—though the text does not say this—he feels no obligation to share anything with his brothers. Both Jacob and Joseph are clueless as to the whirlwind they are about to reap.

Joseph Sold into Captivity, by K. Flavitsky (1855)

Joseph’s Bloody Coat Brought to Jacob, by Diego Velázquez (1630)

If you thought being sold into slavery might humble Joseph a bit, you would be wrong. Through his industriousness, he rises to a position of prominence in the household of his master, Potiphar. But in the process he alienates Potiphar’s wife and the other slaves by claiming he, a foreigner, is second in command and everything in the house is under his control. Her romantic overtures are spurned because he is not about to jeopardize his superior status and offend God in the bargain.[11]

Potiphar’s wife then lies, telling her husband that it was Joseph who tried to seduce her. Though he likely knew the truth of the matter, Potiphar felt compelled to believe her story, but spared Joseph’s life, sending him to a really nice prison instead. There, he began a new rise to prominence in the community, but this time something has changed.

Gone is his customary arrogance. He has finally learned to how to live as a member of a community. The Lord never gave up on him. When Joseph was prepared to listen, he became a powerful instrument in God’s hands, someone who rendered life-saving assistance to his new community: Egypt.

We typically treat this as the climax of the story and what comes after—eventual reconciliation with his brothers, providing refuge in Egypt for the entire family from the famine in Canaan, and the burial of the family patriarch—as a simple coda. But it is in these events where the true meaning of the story can be found.

This tale is not about Joseph. He’s as dysfunctional as the rest of the brood. Rather, it’s about Jacob’s family and God’s desire, one he wishes for every family, that they be reunited and restored. What is the Kingdom of Israel but Jacob’s dysfunctional family writ large? This is why Jacob was renamed “Israel,” which means “one who struggles with the divine.” His life and his family’s internal conflicts are Israel personified. And we, too, are members of that family.

Recently, thousands of refugees from a collectivist society, Afghanistan, arrived at our shores because they were compelled to flee their country. Thousands remain stranded, largely because of the incompetence of our government. We now have an opportunity to restore, perhaps in some small measure, their confidence in our country by welcoming them with open arms and coming to their aid. And should the opportunity to befriend them present itself, I recommend we seize it and, when appropriate, invite them to tell us about their family, their culture and their faith. I’m confident the value of what they teach us will greatly exceed any material assistance we may provide.

[1] Robert L. Heilbroner, The Worldly Philosophers, (New York, NY: Touchstone, 1999), pp. 19-20.

[2] Ibid, p. 20.

[3] Aristotle, The Politics, translated by T. A. Sinclair, (London, England: Penguin Books, 1992), p. 68.

[4] Amy-Jill Levine, The Difficult Words of Jesus, (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2021), p. x.

[5] I don’t mean to suggest that counseling has no value. Heaven knows it has worked wonders for the AFC Richmond soccer team.

[6] Geret Hofstede, Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001), p. 215.

[7] 2 Chron. 11:18.

[8] E. Randolph Richards and Richard James, Misreading Scripture with Individualist Eyes, (Dovers Grover, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2020), pp. 11-17. This is an excellent book.

[9] Old Testament Student Manual: Genesis–2 Samuel, (Salt Lake City, UT: Church Educational System, 2003), p. 93.

[10] Gen. 29:26.

[11] Gen. 38:8-9.