I suffer from chronic pain. I have a degenerative joint and bone disease, which necessitated three major surgeries over the past 48 months. Each operation entailed the installation of metallic support structures in different parts of my body. A fourth procedure is scheduled for this summer.

I also have severe arthritis and a hereditary neurological disorder for which there is no known cure and no effective treatments. It causes loss of strength and extreme discomfort in my lower legs and feet, and will continue to worsen as I age. I could go on, but you get the picture.

I tell you this not to elicit sympathy, complain, or suggest my afflictions are unique, because I know countless others struggle with health problems far greater than my own. Rather, I wish to explain how my personal experience with chronic pain, along with my study of the earthly ministry of our Savior and other readings, have led me to conclude that much of what we teach and preach about pain misses the mark.

Church leaders tell us that pain “ministers to our education [and fosters] the development of such qualities as patience, faith, fortitude, and humility.”[1] That hasn’t been my experience. My faith is no stronger because of my pain, I am more impatient than before and certainly not more humble, and I swear a lot. Anyone with chronic pain who says they don’t swear is either lying or is someone you wouldn’t want to hang out with. Saints can get on your nerves.

My tribulations, I have been told, will help me appreciate the suffering experienced by Christ in the Garden and on the cross. So I’m going to feel better because someone else experienced pain a gazillion times worse than what I am called upon to endure? More to the point, how can I make such a comparison since it is impossible to comprehend the agony, misery and feelings of abandonment experienced by the Savior?

People have urged me to read C. S. Lewis’ monograph, The Problem with Pain, which I have, where he preaches that pain has immense cleansing powers, and in our fallen world suffering serves to turn us towards God. If memory serves, God and I were on pretty good terms before my misery began, and I don’t think my afflictions have done much to improve our relationship.

What is most problematical is Lewis’ assertion that, “God, who foresaw your tribulation, has specially armed you to go through it, not without pain but without stain.”[2] Implicit in this statement is the notion that everything is within our control—so long as we have the requisite faith and determination—and that God would never allow us to be subjected to something we could not overcome.

Who would dare say such a thing to a veteran of the Afghan war suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder because he witnessed an IED decapitate his best friend or, while in the heat of combat, he inadvertently shot and killed a young girl? And what do we say to a young man who developed a drug addiction in utero because his mother was hooked on crack cocaine during pregnancy, was abused by his step-father, and then recruited by a gang while in middle school? You can overcome your addiction and the psychological trauma of your childhood if you just suck it up and pray a lot? Yes, God will not give up on individuals in circumstances such as these, and they desperately need our help, but if they fail it is cruel to attribute their failure to a lack of faith, courage and determination.

I find it instructive that Christ, during his earthly ministry, never lectured people about their need to experience trials and tribulations.[3] His followers didn’t need to be told life is hard nor were they interested in facile explanations for the challenges they confronted. They needed help. And Jesus gave it in abundance.

As Matthew tells us, he healed “every disease and sickness among the people, [who] brought to him all who were ill with various diseases: those suffering severe pain, the demon-possessed, those having seizures, and the paralyzed; and he healed them.”[4] These miracles were often accompanied by valuable insights as to the reason for, and the purpose of, our pains and afflictions.

We are all acquainted with the story of “The Man Born Blind,” whose sight Christ restored. The man’s condition, his disciples believed, must have been attributable to some human failing, so they asked, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” The Savior’s response was somewhat cryptic: “Neither this man nor his parents sinned; but rather that the works of God might be made manifest in him.”[5]

If we believe this man was born sightless just so Jesus could perform an impressive miracle and thereby win some more converts, then we are attributing to God some highly questionable, and arguably inhumane, motives. But if we view Christ’s statement as an invitation to reflect on the role each of us is supposed to play, as embodied beings, in alleviating the suffering of others, then we draw nearer to the truth.

The physical body in Mormonism is generally viewed as something we need to acquire to take the next step in our eternal progression. It’s part of our “checklist gospel.” God has one so, if we are to become like him, we need one, too.

We are admonished to nourish, dress, and use it properly, which meshes nicely with the view that the primary purpose of personal afflictions is to teach an empowered individual “patience, faith, fortitude, and humility.” But it fails to answer the threshold question of why we actually need a physical body in order to progress.

Lewis offers a partial response when he acknowledges that disembodied spirits likely find it difficult, if not impossible, to share ideas or impressions without an external world as a point of reference. Thoughts and passions cannot exist in a vacuum, he postulates; they need to be grounded in objects that can be felt and examined, along with a common medium that forms an environment.[6] But this is an incomplete answer.

I believe we, as spirit children of our Father in Heaven, were unable to learn and experience genuine love for, and develop a familial bond with, our brothers and sisters without a body and a tangible place to interact. But the bodies we have been given are vulnerable and the world we inhabit has finite resources and is sometimes hostile—potential obstacles to our goal of living harmoniously with our fellowman.

A theology that views the principal purpose of pain and suffering as a vehicle for strengthening a person’s faith and teaching humility is centered on the atomized individual trying to realize his personal destiny. To fulfill our mission as embodied beings, more is required. First and foremost, we must see our vulnerabilities and afflictions not just as challenges to be overcome but also as something that makes us dependent upon the generosity of others for our health and well-being. With this perspective, we discover that the principal purpose of our afflictions is to remind us of the reciprocal obligations we owe those around us, who are equally vulnerable.

Disease and injury, in the words of the bioethicist O. Carter Snead, serve to teach us that, “we all pass through stages of life when our will, judgment, strength and beauty are inchoate, obscured, compromised or annihilated.”[7] Emerging from this realization is an obligation “to come to the aid of vulnerable others.”[8]

When we accept that responsibility, our personal self-fulfillment recedes into the background and we become what God meant us to be: the kind of person who makes the welfare of others his own.

By virtue of our embodiment, according to Professor Snead, we are “made for love and friendship.”[9] And affection and companionship find their greatest expression, not when we overcome affliction on our own but when we engage in uncalculated giving to those in need and graceful receiving from those who offer assistance.

In recent months, countless friends and family members have made me the object of their uncalculated giving. Goodies left on the doorstep, unexpected visits, a humorous email, a new book to read—all have buoyed my spirits and strengthened my resolve to serve others with the same pure love of Christ.

There are times, however, when we find ourselves powerless to alleviate the suffering of others or to alter the course of an intractable disease. The Savior taught us how to provide comfort to those in such circumstances, but he did it with such subtlety we don’t see it.

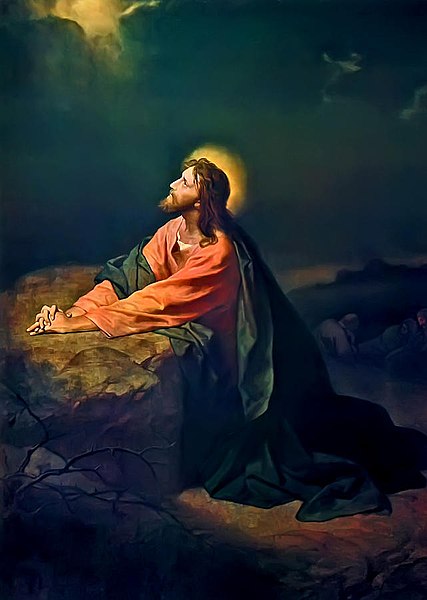

Immediately following the Last Supper, Jesus and his disciples retired to Gethsemane, where he began to pray.

During his supplications, Christ began to grasp the enormity of the ordeal before him, prompting him to seek help from his best friends, Peter, James and John. “My soul is very sorrowful, even to death,” he said; “remain here, and watch with me.” But they fell asleep and let him down.

Jesus, during the hour of his greatest suffering, didn’t need someone to tell him that this is a fallen world, that he had volunteered to take upon himself the sins of the world, or that this experience would make him stronger. He needed someone to sit with him. To rest a hand upon his shoulder as a gentle reminder that a friend was near. To offer a silent prayer on his behalf. But more than anything else, to just be there and mourn with him—he who has mourned more profoundly and more deeply than anyone can possibly imagine.

[1] Elder Orson F. Whitney, as quoted in Spencer W. Kimball, Faith Precedes the Miracle (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1972), p. 98.

[2] Collected Letters of C.S. Lewis (2006).

[3] Jesus, in his parting remarks to his disciples, did tell them they would experience tribulation after he left them but that they would be reunited in peace. John 16:33.

[4] Matthew 4:23-24.

[5] John 9: 2-3 (John Bentley Hart Translation).

[6] C.S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain, (New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 2001), pp. 20-21.

[7] O. Carter Snead, What It Means to be Human: The Case for the Body in Public Bioethics, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2020), p. 8.

[8] Ibid, p. 3.

[9] Ibid, p. 8.

One of your best. (And I’m with you on the swearing.)

Eric, this is so beautiful and thoughtful. I never cease to be in awe at your genuine, humble and curious approach to the gospel. Thank you for sharing.

I couldn’t agree more. The end of this reminds me of Brene Brown’s talk about sympathy vs empathy.

https://youtu.be/1Evwgu369Jw

Sometimes I think we miss the mark in the saying mourn with those who mourn and comfort those in need of comfort.

Anyway, love you and your insights.

Touching meaningful post. Learning to give and to receive are vital parts of life on earth. While my pain isn’t as severe as that of some others, I also suffer from chronic pain. I wish I didn’t. I’d love to have my 21 year old body back and appreciate it a way I never could without the contrast of my current shattered self. I always remember something Sandy Rodas told me. (she had lost a child to crib death). I was saying I don’t know how I could possibly go on or live through a loss of one of my children. And she said, “You live through it because you don’t have a choice.” How very true. You try to improve things, you do a bit or mourning for what might have been, you stamp you feet and feel angry and then you simply take possession of what has been given you and go on because you have to. For me it is about endurance and trying to make the best out of what you have. On another note, I always feel sympathy for the apostles who fell asleep. I fall asleep often when I am trying to stay awake. It isn’t a choice in these cases it is a result of physical weakness. They may have tried every way they knew to stay awake and still fallen asleep. The spirit is willing but the body is weak. All we can do is dust ourselves off and keep trying. What I am attempting to learn is the importance of never giving up and as you point out so eloquently, changing my focus from myself and my own problems to others around me.

Thoroughly enjoyed this one, Eric. (Not that I haven’t your others!) – John

Eric as a fellow traveler on the road called PAIN, I thank you for this post. I read your words with tears in my eyes– no, not tears, rivers falling down my face. I thank you for expressing with words what can be so hard to say and only those feeling their own pain can fully understand.

Thank you for being that hand on my shoulder.

Ingrid

Eric, this piece really moved me and I’m sharing it with others. Thank you for your thoughtful and open sharing of your experience and well-examined (:)) perspective on this issue. I miss being in your ward, but thankfully the blog has helped me stay connected to your wonderful insights on things spiritual.

Thanks, Thorpe, though I fear my “profanity confession” may diminish my chances of securing a temple recommend in the future.

Shireen, you are quite welcome. And thank you for your kind and far-too-generous words. And above all, for taking the time to read my ramblings.

Danielle, thanks for putting me on to Brené Brown’s short talk on “empathy” vs. “sympathy.” While I ascribe different meanings to those terms than she does, I think we both end up in pretty much the same place.

Karen, I have great admiration for your resiliency and faith in the face of serious challenges. Dick and you are an inspiration. And I, too, sympathize with Peter, James and John in this story. Indeed, at the end of my sentence, “But they fell asleep, and let him down,” I should have added, “like we all have.”

John, it’s great to hear from you, as always! And thanks for your feedback, especially since it was complimentary. 🙂

Ingrid, I must tell you that, for reasons too numerous to mention, this was the most difficult and challenging essay I have ever written. It also consumed an inordinate amount of time and energy, leaving me to wonder at the end whether it was worth it. And then I read your comment and I had my answer.

Rest assured, you have done more for us, and countless others, than we can ever do for you.

Nicole, thank you so much for your kind words. You are sorely missed in Arlington, and I hope you are well and thriving wherever in the world you happen to be.

Thank you deeply for this post and the associated hours and emotional journey you commenced while constructing it. My mind is enlightened and my heart enlarged. I am also intrigued by the reciprocal theme as an undercurrent to your points. I think we might get lost in narrowing our view to elements of our lives only serving one purpose or resulting in only one result (usually self serving). Yet, as you reveal this life and our existence is shared, a beautiful truth. Again, thank you.

Eric,

I loved your post! John and I read it together. We are so sorry for your pain and suffering and yet grateful for the insight it provides. Kim had given a talk earlier on Sunday and in a simpler way, was hoping she had been able to convey the message you so eloquently shared. From her talk and then your post we had a very enriching conversation around the dinner table with her and Jeff.

Full disclosure: I swear sometimes and I’m not even in pain.

You are quite welcome, Christine. And thank you for your thoughtful and eloquent comment. Very much appreciated, and also quite comforting.

Karlena, I believe I recall reading in Edward W. Kimball’s biography of his father, Spencer W. Kimball, that after a particularly hard day at work, the prophet banged his head on a kitchen cupboard door while looking for food and exclaimed, “damn!” That story cemented my belief that he was indeed a prophet of God.

Would loved to have heard Kim’s talk and to have participated in your dinner conversation. And, more importantly, eat some of your cooking!

I like the way your brain works!

Thank you for sharing your deep digging through so many and varied sources. “

You put in the work intellectually, physically, emotionally and thoughtfully. Then you enrich our lives by sharing your well-informed analysis with us.

Thank you so very much.

I am sorry you are in such constant pain!

Pamela K.

It’s so great to hear from you Pam, and I so appreciate your kind words. Even more, I greatly admire the courage and grace with which you have confronted similar challenges in your life. You are an inspiration.