Set forth below is a short piece I wrote several years ago about my father for an essay competition sponsored by Jana Riess, a prominent Mormon blogger for the Religion News Service. Even though it was selected for publication on Jana’s website, I am republishing it this Father’s Day weekend as a tribute to my father, one of my heroes.

Not too long ago, stakes and wards were expected to devise fundraising schemes—everything from bake sales, to service auctions, to car washes—in order to subsidize their local operating budgets. Today, funds are dispensed from church headquarters, and local units are discouraged from raising money on their own.

When I was a teenager growing up in the 1960s in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, our stake decided to take fundraising to the next level by purchasing a local agri-business: a pig farm. There was a consensus in the church back then that, although it was good to raise money, it was more virtuous if the money was generated on a farm.

The “porker proposition” was duly presented by our local leaders at a special Melchizedek priesthood meeting. As a lowly deacon, I was not invited to participate, but my father was in attendance. After the project was briefly explained but before a sustaining vote was taken, my dad raised his hand and, in a very gentle and quiet way, began asking questions. “Does anyone in our stake have experience raising pigs?” The answer was no. Contrary to popular misconceptions about LDS congregations in the Midwest, virtually no one in our ward or stake lived on a farm.

“What about a business plan?” my father asked. “Have financial projections been prepared? And can you tell us about the recent performance of the farm under the management of the current owners?”

All of these questions received evasive or incomplete answers, but this seemingly bothered no one—except my dad.

Don’t get me wrong: my father had no inherent objection to ward and stake fundraising activities. But because he owned a small business of his own—a successful aviation insurance company—he knew how difficult it was to manage and sustain a profitable enterprise, especially one surrounded by much larger competitors.

After voicing these concerns and not receiving a satisfactory response, he expressed doubts about the wisdom of proceeding with this undertaking. When he recounted these events to me a few years later, I instinctively assumed that others would give considerable weight to his views since he was one of the few entrepreneurs in our ward. Most everyone else was affiliated with the university or was a salaried employee of a local company. As it turned out, he was the lone dissenter, and his reservations and objections were summarily dismissed—the train for hog heaven was leaving with or without him.

Within eighteen months, the pig farm was insolvent. Because no one believed the project could be salvaged, the decision was made to shut it down and liquidate its assets. At the end of the day, there was a net loss of about $12,000. Back in the sixties, $12,000 was real money.

My father certainly never said, “I told you so,” but I thought some of our local leaders would admit their mistake to my dad, at least in private. I soon discovered, however, that there was a better chance that one of those little porkers would take to the air under his own power than someone would say to my dad: “We should have listened to you, Brother Facer.”

Instead, a few proffered rather dubious explanations for the venture’s demise, such as “the farm would have succeeded if we had all been more righteous” or “the Lord was trying to teach us a lesson in humility.”

Some in our ward were offended by my dad’s temerity, his refusal to go along with the herd, so to speak, and his willingness to openly question the business acumen of his church leaders. There was little doubt in his mind that he was not considered for certain leadership callings because of the stance he took on this issue.

I was surprised and disappointed by the way my father had been treated. But, to his credit, he never exhibited any bitterness or harbored any ill will towards his fellow saints. Instead, he quietly went about his business, attending his meetings, doing his home teaching, and working diligently with the Boy Scouts.

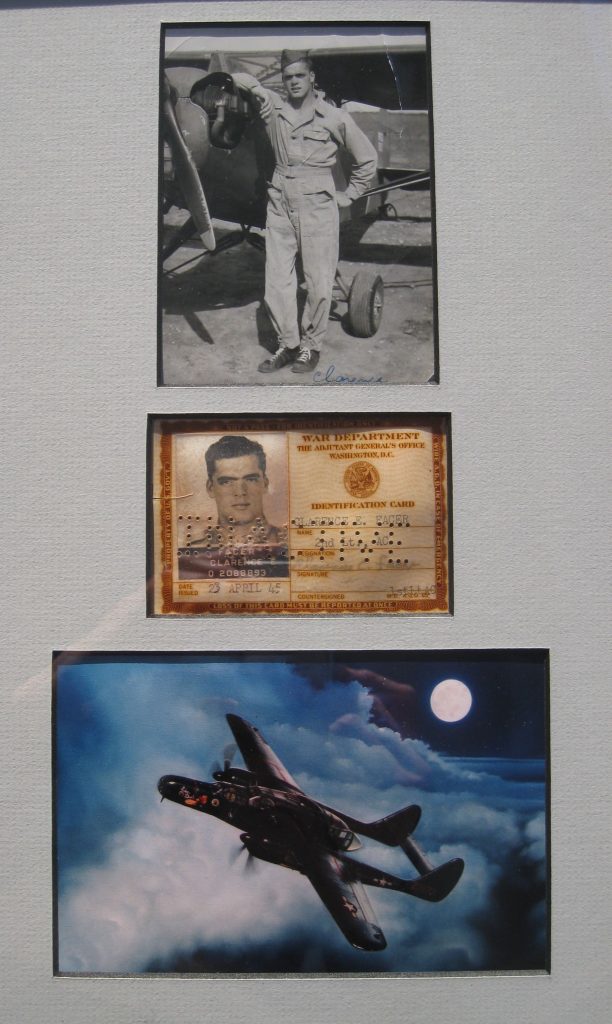

On May 13, 2014, my father died. A veteran of the Second World War, the father of four reasonably well-adjusted boys, and forever a devoted husband, his ability to preserve his independence of mind while remaining loyal to his faith community is one of the things I admire most about him.

I miss him terribly.

I can see your father’s influence in your ability to review and analyze your approach to life, though I wonder if your parents had moments at the dinner table where they thought, “ I want my children to be critical thinkers and to stand up for the things in which they believe. To defend their opinions and honor their values…

Not at dinner though. Seriously, just eat what’s on the table and shut up about it.” Or maybe that only happened at our table.

It takes great courage to go against the crowd. A great role model for the family in doing that and how he handled it after the demise of the enterprise.

Inspiring story! I’m glad he asked those questions rather than keeping them to himself, even though they weren’t taken seriously. I believe others may have harbored a sense of regret for not heeding his insights, especially after the business failed; hence, he felt there was no need to flog a dead horse. Your dad was a wise and brave man.