In the mid-1970s, sportswriter Frank Deford was sent by his employer, Sports Illustrated, to cover an NCAA convention in Chicago. The day following his arrival, Deford wandered into a nearby coffee shop to get some breakfast. The place was quite crowded, but he spied a lone vacant seat at the end of the counter and seized it.

He initially took no notice of the person sitting next to him. But after unfolding his newspaper, he glanced to his left and was taken aback by a man attired completely in white. Yes, it was none other than the legendary founder of Kentucky Fried Chicken, Colonel Harland Sanders.

The Colonel greeted him and a brief conversation ensued. As Deford placed his order and the Purveyor of Poultry finished his breakfast and asked for his bill, he stood and told the sportswriter how much he had enjoyed their chance encounter. Deford turned to bid him good-bye, whereupon the Colonel said: “So, young man, I want to give you an important piece of advice.” Holding up his cane for emphasis he declared: “If you want people to listen to you, … [pause for dramatic effect] … wear a white suit.”[1]

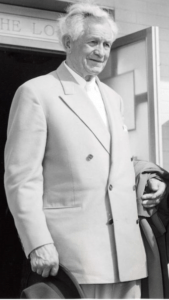

I’ve often wondered whether Harland Sanders had acquired this bit of wisdom from David O. McKay, the prophet of my youth, wh o often wore a double-breasted white suit, in stark contrast to his more conservatively attired colleagues. He also consciously wore his snow-white hair longer than the prevailing style to augment his striking appearance, something in which he took considerable pride.

o often wore a double-breasted white suit, in stark contrast to his more conservatively attired colleagues. He also consciously wore his snow-white hair longer than the prevailing style to augment his striking appearance, something in which he took considerable pride.

Even his son acknowledged that “if father had any weaknesses they would be two: He drives too fast; and the other is vanity.” (As to the first shortcoming, on one occasion, in his later years, McKay was caught speeding and issued a citation. But he was undeterred, telling the officer: “I’m glad to get this ticket. Some have said I am slowing down [but] this is proof that I’m not.”[2]

President McKay was also known for his open-mindedness and tolerance—except when it came to fanatical or rigid thinking. According Gregory Prince and Wm. Robert Wright, authors of an exceptional biography of McKay and his times, he once chided his fellow apostle, John Widtsoe, whose wife was on a crusade against chocolate because of the stimulants it contained, saying, “John, do you want to take all the joy out of life?”[3]

His early doubts concerning Mormonism and realization that neither he nor the church had all the answers and sometimes got things wrong undoubtedly contributed to his humility and his tendency to shun absolutes. “Sound independent thinking should be encouraged rather than discouraged,” McKay once asserted, noting that “careful logical analysis, coupled with a sincere desire to find the truth is praiseworthy.” As his son, Llewelyn McKay observed: “Father’s religion is concerned with large, all-embracing spiritual issues which reach out to include rather than to exclude; it unites rather than divides.”[4]

President McKay, however, did have one blind spot—a divisive religious prejudice, one shared by many of his colleagues: a pronounced enmity towards the Catholic Church. This preconception would ultimately lead to a public relations nightmare for the church and a personal reckoning for its leader.

The origins of David O. McKay’s deep distrust of Roman Catholicism can be traced to the early days of Mormonism when anti-Catholic sentiments were prevalent throughout the United States. As a result, many in the church were predisposed to believe that “the great and abominable church” mentioned in the Book of Mormon was, in fact, the Catholic Church.

On a personal level, McKay’s direct interaction with the Roman church was in the form of his relationship with one Bishop Duane G. Hunt, who presided over the only Catholic diocese in the State of Utah. That relationship spanned a period of almost 40 years. At times it was strained, even tumultuous.

On a personal level, McKay’s direct interaction with the Roman church was in the form of his relationship with one Bishop Duane G. Hunt, who presided over the only Catholic diocese in the State of Utah. That relationship spanned a period of almost 40 years. At times it was strained, even tumultuous.

Public radio broadcasts made by Bishop Hunt and pamphlets he published for the purpose of shoring up his small flock and raise funds for the diocese were often perceived by President McKay, J. Reuben Clark and other church leaders as direct threats, as attempts to lure Latter-day Saints away from the fold. Indeed, when Bishop Hunt, during a radio address in 1948, explained that the primacy of the Pope and the Holy See in Rome are core beliefs of Catholicism, President Clark construed this as a “declaration of war.”[5]

A pamphlet called “A Foreign Mission Close to Home!” which was written for Utah Catholics and intended to raise money for the underfunded parishes, sparked another round of theological warfare because McKay and his colleagues misunderstood the title. In the Catholic vernacular, “mission” refers to a simple, striving parish, not to proselytizing. Putting aside the obvious double standard—the Mormon Church was sending thousands of missionaries to South America with the express purpose of converting Catholics, among others—proselyting was never Bishop Hunt’s intent. McKay and his colleagues, however, were not convinced and “subsequently took unwarranted and damaging action in retaliation.”[6]

Even though he was clearly the innocent and aggrieved party, Hunt showed commendable charity, restraint, and goodwill as he strove to mend fences with McKay and other church leaders. While these efforts were largely successful on a personal level, President McKay continued to draw a distinction between those Roman Catholics, who were friends, and the church to which they belonged, which he disdained. On one occasion, while speaking at a meeting of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve, he identified Communism and the Catholic Church as the two biggest threats to the restored gospel.[7]

All of this ultimately came to a head in 1958 when Elder Bruce R. McConkie published, without the consent or knowledge of the First Presidency, a book called Mormon Doctrine. It was replete with doctrinal errors and, under the heading of “Catholicism,” was this entry: “See Church of the Devil.” And under that heading, McConkie pulled no punches: “The Roman Catholic Church [is] specifically—singled out, set apart, described, and designated as being ‘most abominable above all other churches.’”[8] To support that allegation, he cited passages from the Book of Mormon.

This was a profound embarrassment for the church. And, not surprisingly, Bishop Hunt’s reaction to the book was one of great sadness. With tears in his eyes he said: “We are your friends. We don’t deserve this kind of treatment!” President McKay was infuriated by what McConkie had done and, from that day forward, no General Authority was allowed to publish a book without first obtaining the approval of the First Presidency. McKay then ordered the removal of Mormon Doctrine from the shelves of church-owned Deseret Book.[9]

When McKay confronted the religious intolerance in the pages of McConkie’s book, it appears he saw something more than false doctrine. It would seem he also saw his own reflection, one that bore scant resemblance to the striking man known for his spiritual generosity and acceptance of others. In the aftermath of this debacle and for the remaining decade of his life, David O. McKay quietly abandoned his antipathy for Roman Catholicism. He realized that Bishop Hunt was a true friend without a hidden agenda.

One year latter, President Stephen L. Richards, one of McKay’s counselors, passed away. While presiding at the funeral, he saw Bishop Hunt in the audience and was so touched that afterwards he sent him a personal note: “When I saw you … paying tribute of respect to my departed friend and associate, Stephen L. Richards, I wanted to shake your hands in personal appreciation.”

One year later, Bishop Hunt unexpectedly died. President McKay promptly issued a statement to the media praising Bishop Hunt as an “eminent and devoted leader” of his church who provided “spiritual guidance” to his flock. Beyond these words, the prophet paid personal respect to Hunt by attending his funeral mass—the first mass he had attended in his life—at the Cathedral of the Madeleine.

A decade later, Hunt’s successor, The Most Rev. Joseph Lennox Federal, reciprocated the gesture by attending McKay’s funeral. Then, as the cortege passed the Catholic Cathedral on its slow procession along South Temple Street towards the city cemetery, Rev. Federal ordered the bells tolled in a final demonstration of respect.[10]

Few things in life are more difficult than enduring an injustice without responding in kind. Staunchly objecting to unfair treatment while refraining from public provocations that may only widen the divide and harden the false beliefs of the perpetrator requires inordinate restraint. While patience, long-suffering, and love unfeigned deny us the transitory satisfaction of victory or revenge, they can yield something of eternal value: a mighty change in the heart of the wrongdoer.

During the last years of President McKay’s life, a noticeable change occurred in Salt Lake’s attitude towards the Vatican. Indeed, over time, the church came to respect and support the work of organizations such as Catholic Charities, which has far more experience in responding to international humanitarian crises than it does. Collaboration on that front and others, such as coordinated efforts to advance the cause of religious liberty, ultimately led last year to the first meeting ever between an LDS Prophet and a Catholic Pope. All of this was made possible because one Catholic bishop responded with quiet perseverance and genuine forgiveness in the face of religious intolerance.

[1] Deford, Frank Over Time, pp. 58-59, Atlantic Monthly Press, 2012.

[2] Bringhurst, Newell G. (Fall 1998). “The Private versus the Public David O. McKay.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 39(3), pp. 25, 29.

[3] Prince, Gregory A. & Wm. Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, (Univ. of Utah Press, 2005), p. 23.

[4] McKay, Llewelyn R. Home Memories of President David O. McKay, p. 272, Desert Book Co., 1967.

[5] Rise of Modern Mormonism, p. 114.

[6] Rise of Modern Mormonism, p. 119.

[7] Rise of Modern Mormonism, p. 121.

[8] McConkie, Bruce R., Mormon Doctrine, p. 129, Desert Book Co., 1958.

Dear friend

This article causes me to think of Archbishop Timothy Dolan, a friend not only to the church, but personal friendships with a number of the Apostles. An absolute delight!

(I love his politics, too!!! )

I really appreciate how you illustrate their intolerance in a context of human frailty and shortsightedness. I’m so grateful for how far we (collectively, as a church community) have come. I hope we will continue to move toward more inclusion and love. Also, this: “His early doubts concerning Mormonism and realization that neither he nor the church had all the answers and sometimes got things wrong undoubtedly contributed to his humility and his tendency to shun absolutes.” Oh, that every leader was a little more this way! Thanks for all the enlightening and interesting stories you share. I feel like I learn so much and always enjoy reading!

Always nice to hear from you, Michael. And, yes, Archbishop Dolan is a good friend of our church as well as a good steward over his own flock. There is no doubt in my mind that he and his colleagues receive divine guidance and spiritual promptings in the same manner as do the leaders of the LDS Church.

S Barnhart, I share your sentiments completely. This story is inspiring on multiple levels. For a man of David O. McKay’s age to abandon a lifelong prejudice and diligently work to correct his past missteps is a perfect example for all of us. I’m much more inclined to trust and follow a leader who will take ownership of his mistakes and promise to do better than someone who assures me that he and the institution he represents are incapable of leading me astray.

Eric, as you know, I am not LDS, so please forgive any naivete in this question. Last week, my wife and I were on vacation in Idaho and we stopped by the LDS temples in Idaho Falls and Rexburg. At the Rexburg temple, a wedding was about to begin and the man who was greeting the guests at the door of the temple was wearing a white business suit, much like that of David McKay in the picture above. Are white suits a common thing in the Church?

Your question is quite understandable, Doug. White suits are generally only worn inside LDS temples. Indeed, the clothing worn by those who both officiate and participate in the ordinances and ceremonies in the temple are almost entirely white. (Most folks entering the temple carry a small bag containing the required white temple clothing, and male/female locker rooms are provided where they can change.)

Having said this, there is no rule against wearing a white suit to church on Sunday. Indeed, there was a teenager in the last ward I attended who did that just to show his independence. I respect that since I typically decline to wear the customary white shirt to church, opting instead for blue or pink, and even stripes when I’m feeling particularly rebellious.

It was an anti-Catholic assumption that still persists in Mormonism…a later generation became more subtle but are infinitely more dangerous.

Just as they are playing down the racial curses today.