In the late summer of 1786, the Continental Congress authorized a meeting in Annapolis, Maryland to address the problem of burdensome restrictions placed by the various states on interstate commerce. Only five states sent representatives. Lacking a quorum, they were unable to conduct business. So, with time on their hands, a group of them planned a rebellion.[1]

The first step in their plot was to send a seemingly innocuous letter—penned by Alexander Hamilton—to the Continental Congress. In this missive, he asked Congress to direct the states to appoint commissioners to gather in Philadelphia in May of 1787 to consider such changes to the Articles of Confederation as would “render the constitution of the federal government adequate to the exigencies of the union.”[2] Congress assented to their request but limited the remit of the Philadelphia gathering to revising the Articles of Confederation.

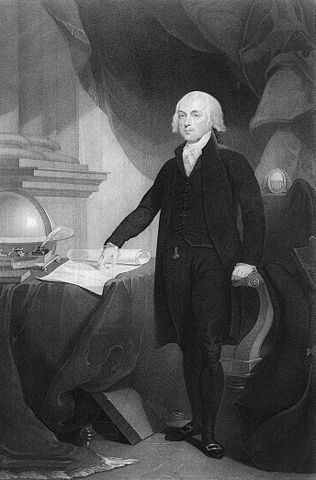

But Hamilton and his co-conspirators—which included James Madison and Edmund Randolph, governor of Virginia—intended to scrap the Articles because, in their opinion, they were irredeemably deficient. Congress’s inability to levy taxes, raise an army, and regulate commerce, combined with the absence of a chief executive to enforce and execute the laws of the land, had brought the country to the brink of bankruptcy. Further, the new nation was powerless to suppress domestic uprisings—such as the one currently unfolding in Massachusetts (Shay’s Rebellion).[3]

As we know, they accomplished their objective though it took nearly four months and, on more than one occasion, the Constitutional Convention almost disintegrated over seemingly insurmountable differences. When a consensus on the text of the Constitution was reached and the document signed, no one was satisfied, but all believed it would result in “a more perfect union.” Benjamin Franklin, a delegate from Pennsylvania, was astonished “to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does”[4] and others saw in it the hand of Providence. But Gouverneur Morris, another Pennsylvania delegate, believed the Constitution was simply “the work of plain, honest men.”[5]

Such optimism notwithstanding, the Convention delegates all knew the road before them was strewn with obstacles and success was not guaranteed.[6] A republic the size of the original thirteen states—let alone fifty—was unprecedented. Indeed, highly respected political philosophers, such as Montesquieu, believed the diversity of economic, cultural and religious beliefs in an area the size of the United States made it nearly impossible for the pluribus to coalesce into an unum.[7]

Inasmuch as the U.S. Constitution is the oldest extant charter of national government in the world and indisputably one of the most successful in history, it would appear the Convention’s optimism was warranted. So, it comes as a surprise to most Americans that virtually all of the major founders—plus many lesser luminaries such as Samuel Adams, Elbridge Gerry, Patrick Henry, John Jay, John Marshall, Benjamin Rush, James Monroe and Thomas Paine—became disillusioned with the national government they had created and believed it would last no more than a generation or two.[8]

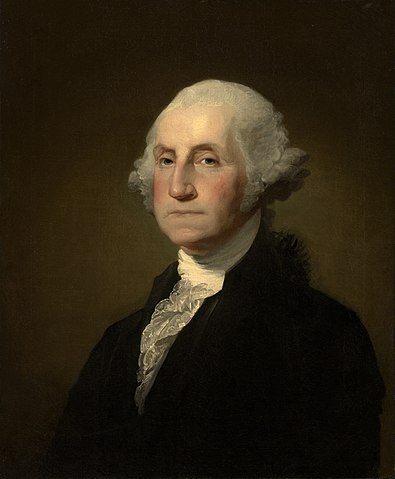

Washington, for example, soon became distressed over the warring “factions” in the country, what we call political parties. They made it “difficult, if not impracticable, to manage the Reins of Government or keep the parts of it together,” he lamented.[9] The two major parties—the Federalists and the Republicans[10]—each accused the other of being enemies of the Constitution.[11] Perhaps Washington was naïve for thinking people with differing views would not coalesce into organized groups. But this, according to one of his biographers, was “‘The Age of Passions’—the most fervently partisan decade in American History.”[12]

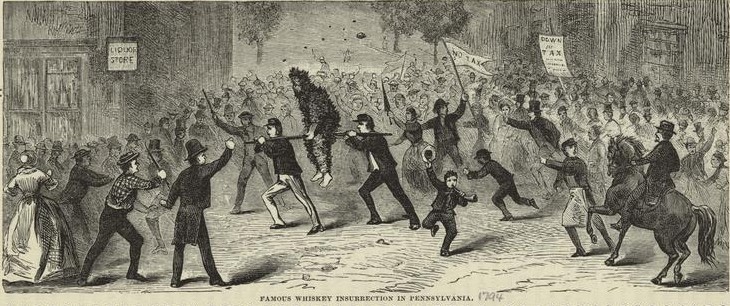

The divisions and hostilities he witnessed as president—both in society as a whole and within his own cabinet—beggars belief. It reached its nadir in 1794 with the Whiskey Rebellion—an uprising in Western Pennsylvania against the new federal tax on whiskey. Mobs assaulted the tax collectors and some 7,000 armed insurgents attacked an Army outpost in Pittsburgh. Washington had to dispatch 13,000 state militia—a force larger than what he required to defeat the British at Yorktown—to quell the insurrection.[13] Washington was not optimistic about the future of the Republic at the end of the Constitutional Convention—reportedly saying it would last no more than twenty years—but as his life drew near its end, he grew even more pessimistic.[14]

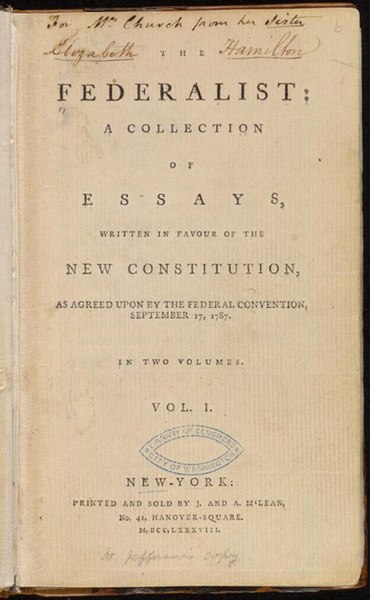

Alexander Hamilton shared Washington’s pessimism at the end of the Convention. He felt his colleagues had failed to provide for a sufficiently strong central government, the lack of which was the principal reason why they had gathered in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. Nevertheless, no one fought more tirelessly to secure its approval by the states. Hamilton authored more of the Federalist essays than his colleagues James Madison and John Jay and produced them at blinding speed.[15]

Hamilton’s patron, George Washington, appointed him Treasury Secretary, a position he held during Washington’s first term and half of his second.[16] Hamilton felt emboldened to advance numerous reforms, such as a sweeping redesign of the government’s fiscal affairs, modeled after the British financial system. He then ventured beyond his portfolio in Treasury to strengthen the executive’s power to make treaties, create a standing army, and secure the independence of the judiciary.[17]

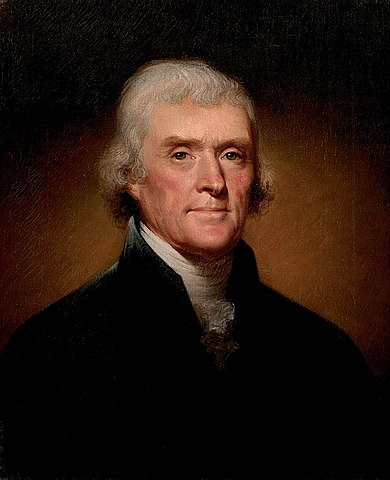

In these endeavors, Thomas Jefferson was his staunch opponent since Jefferson had an abiding fear of centralized authority. But Hamilton outmaneuvered Jefferson every step of the way, though this did not cause Jefferson to lose faith in the American experiment. His zeal for democracy was unequaled by his co-founders (though that would change later in life). Besides, when Jefferson won the presidency in 1800, he was able to dismantle much of what Hamilton had built.

This caused Hamilton to despair mightily for the future of his country and the Constitution for which he had sacrificed so much. In a letter to Gouverneur Morris, he complained that for his labors to prop this “frail and worthless fabric,” he had nothing save “the murmur of its friends no less than the curses of its foes for my rewards.” He concluded by saying: “Everyday proves to me more and more that this American world was not made for me.”[18]

Jefferson’s optimism regarding the future of the United States held firm until the final decade of his life. Growing divisions between the North and the South over slavery, combined with the centralization of power in the federal government, caused him to lose hope.[19] Arguably, however, his forebodings began earlier when he witnessed three separate secession movements by the New England states, two of which occurred while he occupied the White House.[20]

Of all the founders, Jefferson discerned the most immediate potential cause of disunion: involuntary servitude. In hindsight, the North’s victory in the Civil War seems inevitable given its huge advantages in money, men, and materiel. Nevertheless, if the outcome of certain events had been different, the South would have likely prevailed in its goal to separate from the union.[21]

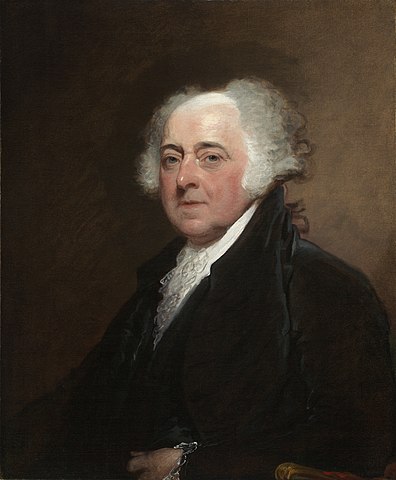

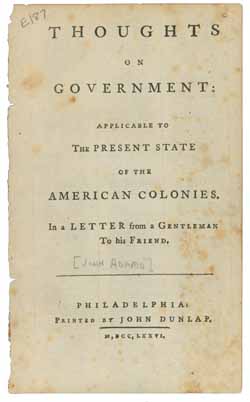

John Adams was without equal in his depth of knowledge on the subjects of law, politics and history. He read more widely and voraciously than his colleagues, including Jefferson and Madison. And from his studies he gleaned this insight: “republican government depended not just on the right institutions but on the people’s character.”[22] Virtue, patriotism and sacrifice—a willingness to put the public welfare ahead of one’s own material interests—were essential to the preservation of liberty.

The unity of, and the sacrifices made by, his fellow patriots during the Revolutionary War gave him reason to believe this bold attempt at constitutional government would succeed. But what he witnessed as Washington’s vice president convinced him that “human Nature will be found the Same in America as it has been in Europe.”[23] And barely a month after his inauguration, he concluded the republic would not last long and believed there was no solution “but another Convention.”[24]

Around fifteen years later, in the midst of the War of 1812, Adams shifted his focus from his fellow citizens’ obsessive preoccupation with material gain to what it produced: prosperity. In a letter to his son, John Quincy, he said: “human nature cannot bear Prosperity. It invariably intoxicates individuals and Nations.… Prosperity has thrown our dear America into an easy trance for 30 years. The dear delights of Riches and Luxury have drowned all her intellectual and physical Energies.” [25]

But Adams failed to explain how prosperity corrupts democracy and how such corruption is manifested in the workings of government and in the minds of its citizens. That insight came many years later from someone else, a Frenchman—Alexis de Tocqueville—who was arguably the most prescient political theorist and the greatest student of American government and society.

Although Tocqueville shared Adams’ concerns about prosperity, he believed America had struck the proper balance between the pursuit of gain and civic virtue. An American, he observed, will pursue wealth with an extraordinary single mindedness, but “a moment later he will dedicate himself to the public’s affairs” with equal intensity. “At times he seems animated by the most selfish greed, and at other times the most ardent patriotism.”[26] Why? Because “Americans see their liberty as the best instrument and strongest guarantee of their well-being.” In other words, they wish “to secure for themselves a government that will allow them to acquire the goods they desire and that will not interfere with the peaceful enjoyment of those they have acquired already.”[27]

Prosperity, however, can corrupt this imbalance, said Tocqueville, if people develop an abiding “dread of material disorder.” This will arise when their material well-being displaces all other priorities in their lives. When public tranquility becomes what they desire most, they will willingly “surrender new rights to the central power”—even a despot—“to attain it.”[28]

Tocqueville did not fear the rise of a Caesar in a democratic society; rather, the despotism he foresaw “would be more extensive and more mild, and it would degrade men without tormenting them.”[29] Tocqueville called this “administrative despotism,”[30] one that evolves over time, accreting more and more power since “it is in the nature of every government to seek to expand its sphere continually.”[31]

The citizenry is not blind to the freedom they are forfeiting to ensure tranquility. But they “console themselves for being wards by imagining that they have chosen their own protectors” each election cycle. “Each individual allows himself to be clapped in chains because he sees that the other end of the chain is held not by a man or class but by the people themselves.”[32]

The individual’s apathy causes him to withdraw into himself, cutting him off from society and becoming “a stranger to the fate of all others. * * * * He exists only for himself, and if he still has a family, he no longer has a country.”[33] The administrative state—which Tocqueville defined as the entirety of the federal government—encourages such behavior in society by assuming “sole responsibility for securing their pleasure and watching over their fate.”[34] Most believe that government performs these functions poorly, “but all believe that the government must act continually and take a hand in everything.”[35]

For its part, the government accomplishes its primary goal: a compliant and docile citizenry. By keeping “them in childhood irrevocably,” it seeks to relieve “them entirely of the trouble of thinking and the difficulty of living.”[36] Rather than tyrannize, it reduces the “nation to nothing but a flock of timid and industrious animals, with the government as its shepherd.” And those animals, according to Tocqueville, have “lost the ability to think.”[37]

Tocqueville wrote this prophetic warning in 1835. Our history over the past 100 years reveals how it is gradually being fulfilled.

A recent poll illustrates how the administrative despotism Tocqueville warned against is now a reality. A study by Pew Research Center on June 10, 2022, reveals that “only 20% say they trust the government in Washington to do the right thing just about always or most of the time.” And yet a majority of adults “say that the government should do more to solve problems.”[38] And a staggering 59 percent of survey respondents say it is the government’s job “to protect people from themselves.”[39]

The infantilization of America which Tocqueville feared manifests itself not only in our government but also in our educational and ecclesiastical institutions where ideological conformity is lauded and critical thinking often discouraged. For example, professors, out of fear of reprisal, will often refrain from critiquing ideas they believe to be ill-supported or simply flat-out wrong—including those proffered in class by students. Those same students often work to disinvite visiting speakers—almost always speakers with conservative viewpoints—not just because they disagree with their views but because those views “would be dangerous, emotionally devastating, a form of violence.”[40] Not surprisingly, self-censoring by students who do not subscribe to the prevailing campus ideology is also quite prevalent.

Conservative universities can also be hostile environments for those with a liberal perspective. In the most recent College Free Speech Rankings, Brigham Young University (my alma mater) finished dead last among 55 top universities as the most difficult place for liberal-minded students to express their views.[41] While professors and administrators are generally supportive of free expression on campus, students frequently are not. As one graduate said: “My support of the LGBTQ community was … mocked by students during a religion class. I participated in a BYU College Democrats vs. BYU College Republicans debate and our side was booed loudly so many times, the moderator had to keep calming the crowd so our viewpoint could be heard.”[42]

Such behavior flies in the face of Enlightenment principles which gave birth to our society’s mechanisms for generating knowledge and ascertaining truth. We can see this at work in our judicial system where competing adversaries make their case and an impartial jury renders a decision. Or in the scientific method where scholars put forth evidence-backed claims and other scholars seek to refine those claims or falsify them altogether. Or in newspapers which publish stories presenting competing viewpoints—stories fact-checked by scrupulous editors.[43] But our government, legal system, media, universities, and even scientists,[44] have abandoned these norms to a significant degree. And many blame social media.

All humans are prone to confirmation bias, i.e., preferring information that validates their religious, political and economic views versus that which supports the opposite. The author and social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, in a recent article in The Atlantic, “After Babel: How Social Media Dissolved The Mortar of Society and Made America Stupid,” asserts that Twitter, Facebook and other platforms transformed confirmation bias into a psychosis. They accomplished this by adding “Like,” “Share,” and “Retweet” buttons to their sites. This allowed Facebook and Twitter to create algorithms that would funnel information to a user that would likely elicit a similar response. One of the engineers who created the “Retweet” button later regretted his contribution, believing, “We might have just handed a 4-year-old a loaded weapon.”[45]

This not only encouraged individuals to pursue narcissistic isolation at the expense of community involvement (one of Tocqueville’s greatest fears); it brought out “our most moralistic and least reflective selves.” This exposed one of democracy’s great weaknesses: its “vulnerability to triviality.”[46] As James Madison insightfully observed during the debates on the Constitution, when extreme factions faceoff, “the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions and excite their most violent conflicts.”[47]

I believe the solution to this impasse—at least a solution within our individual control—involves two steps. First, epistemic humility on the part of everybody is essential. At best, our understanding of an issue is only 20% (pick any number you like—as long as it’s a low one). We can combat that deficiency by making a serious effort to learn the other side of an issue as well as our own. George Washington was meticulous about doing this while president before he made a decision.[48]

Second, part of our learning must include human interaction with those with whom we disagree. According to a recent poll by the University of Chicago’s Institute of Politics, 73 percent of Republicans and 74 percent of Democrats think the other side are authoritarian bullies.[49] Our only hope for reducing these numbers is by swallowing our pride and extending the hand of friendship to those on the other side of the political divide.

And when we do interact with those who see the world differently than ourselves, we must be willing to listen. Don’t think about what you are going to say in response. Just listen. The French philosopher, Simone Weil, said, “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity. Absolute unmixed attention is prayer.”[50] And finally, before you even begin the conversation, ask yourself, “Do I want to win an argument or do I want to learn something and politely share with others my thoughts and ideas? If it’s the former, then turn around and go home.

America’s democracy, John Adams said as his life drew to a close, is “destined to form, in future history, the brightest or the blackest page, according to the use or the abuse of those political institutions by which they shall, in time to come, be Shaped by the human mind.” Each of us is accountable for the shape of our own mind and has the power to influence, and learn from, the minds of others. Tocqueville believed that a fundamental pillar of America’s democracy was the “art of association,” of the ability of its citizens to gather in community organizations for the purpose of learning and advancing a noble cause. The loss of this art, he added, poses a “serious threat to liberal societies.”

As one final suggestion, consider James Madison, the lone Founding Father who never despaired for the future of our country. The reasons were likely his temperament and his outlook on life.

His contemporaries described him as composed, steady and unflappable. He was almost “maddeningly unperturbed” when the New England states threatened to secede and when (while he was president) the Capitol was ransacked and the White House was put to the torch by British troops during the War of 1812. But he simply refused to despair. He also expected far less from politics than most of the founders and knew it was foolish to believe government could be the source of genuine happiness.[51] Not surprisingly, he lived longer than Washington, Hamilton, Jefferson and Adams.

If we can: (i) more closely approximate Madison’s outlook on life, (ii) embrace Washington’s habit of considering all sides of an issue before lending our support, (iii) break (or at least loosen) the shackles of social media, (iv) and exchange self-isolation for reconnecting with our community as Tocqueville recommended, then perhaps we will discover that Otto von Bismarck was right: “There is a Providence that protects idiots, drunkards, children and the United States of America.”

[1] Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution, (New York, New York: Random House, 2009), pp. 18-20.

[2] Ibid, p. 19.

[3] Ibid, pp. 20, 27-29.

[4] Max Farrand, ed., The Records of the Constitutional Convention: Vol. II, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1911), p. 642.

[5] Plain Honest Men, p. x.

[6] Dennis C. Rasmussen, Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of America’s Founders, (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2021), p. 6.

[7] Charles de Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, trans. by Thomas Nugent (Overland Park, KS: Digireads.com, 2020), p. 134-135. James Madison offered countered Montesquieu’s argument by noting that a strong, large republic against powerful special interests which can more easily influence a state government. James Madison, Madison: Writings, “Federalist No. 10,” (New York, New York: The Library of America, 199), p. 160.

[8] Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution, (New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), p. 365.

[9] Fears of a Setting Sun, p. 8.

[10] This is not the Republican Party we know today, which was formed in 1854 to combat slavery.

[11] Fears of a Setting Sun, p. 11.

[12] John Rhodenhamel, George Washington: The Wonder of the Age, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2017), p. 234.

[13] William Hogeland, The Whiskey Rebellion: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and the Frontier Rebels Who Challenged America’s Newfound Sovereignty, (New York, New York: Scribner, 2006), p. 7.

[14] Fears of a Setting Sun, pp. 9, 21.

[15] Ibid, p. 61.

[16] Hamilton left the administration in 1795 because he was broke and needed to return to his law practice so he could provide for his family.

[17] Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, (New York, New York: The Penguin, Press, 2004),487-488.

[18] Ibid, p. 658.

[19] Fears of a Setting Sun, pp. 9-10.

[20] Edward Payson Poowell, Nullification and Secession in the United States: A History of the Six Attempts During the First Century, (Clark, New Jersey: The Lawbook Exchange, 2017). The first secession attempt was triggered by perhaps his greatest accomplishment as Chief Executive: the Louisiana Purchase. But much of New England felt this would open the door many new slave states, weakening the influence of North in Washington. The second was a national embargo on all foreign trade occasioned by the British impressment of seaman of Americans who crewed U.S. commercial and navy vessels. The third was the War of 1812 which threatened the livelihood of New England since it depended heavily on trade with Great Britain.

[21] For example, if Lee had defeated McClellan at Antietam, Great Britain was poised to recognize the South, which would have forced the North to either end its blockade of southern ports or to fight a third war with England. Stephen W. Sears, Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam, (New Haven, Connecticut: Ticknor and Fields, 1983), 333-334. In addition, if the assassination attempt in the fall of 1864 had succeeded, McClellan, who favored separation from the South, would likely have won the presidency in November of that year.

[22] Fears of a Setting Sun, p. 103.

[23] Ibid, p. 110.

[24] Ibid, p. 121.

[25] Ibid, p. 140.

[26] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. by Arthur Goldhammer, (New York, New York: The Library of America, 2004), p. 631.

[27] Ibid, p. 632.

[28] Ibid, pp. 793, 794, 801

[29] Ibid, p. 817.

[30] Ibid, p. 819.

[31] Ibid, p. 794, n.1.

[32] Ibid, p. 818.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid, p. 791. This observation is based on what Tocqueville witnessed during the French Revolution.

[36] Ibid, p. 819.

[37] Ibid, P. 821.

[38] “Americans’ Views of Government: Decades of Distrust, Enduring Support for Its Role,” Pew Research Center, June 6, 2022, accessed on July 1, 2022.

[39] Emphasis added. Only 38% of Republicans endorse that belief while 77% of Democrats embrace it.

[40] Jonathan Haidt, The Atlantic, “After Babel: How Social Media Dissolved the Mortar of Society and Made America Stupid,” (May 2022, p. 65). This article is available, though under a different title: Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid.)

[41] “2020 College Free Speech Rankings,” RealClear Education, accessed on November 12, 2020.

[42] David Noyce, “This Week in Mormon Land: Liberals leery at BYU,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 5, 2020. In February 2021, BYU’s Committee on Race, Equity and Belonging made public a report exposing widespread and significant concerns about the mistreatment of minorities on campus. Courtney Tanner, “BYU released a report saying its students of color feel ‘isolated and unsafe’ due to racism on campus,” The Salt Lake Tribune, (February 27, 2021), accessed on July 3, 2022.

[43] Jonathan Rauch, The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth, (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2021), pp. 85-102.

[44] Ibid, p. 73 (The answer is: of course scientists are biased.”)

[45] “After Babel,” pp. 58, 60-61. The Dunning-Kruger effect offers a more sophisticated explanations as to why it is difficult for people to recognize deficiencies in their own knowledge.

[46] Ibid, p. 58.

[47] Madison: Writings, p. 162.

[48] Fears of a Setting Sun, p. 19. The British political philosopher, John Stuart Mill, is an excellent role model: “… the only way in which a human being can make some approach to knowing the whole of a subject, is by hearing what can be said about it by persons of every variety of opinion, and studying all modes in which it can be looked at by every character of mind.” Mill went on to say that this is a lifelong process; as new information becomes available on the subject, we must be open to changing our minds. John Stuart Mill, The Basic Writings of John Stuart Mill: On Liberty, The Subjection of Women & Utilitarianism, (New York, New York: The Modern Library, 2002), p. 22.

[49] Christian Britschgi, Reason, “70 Percent of Republicans and Democrats Agree: The Other Side Are ‘Bullies,’” (July 1, 2022), accessed on July 3, 2022).

[50] Barry Lopez, Embrace Fearlessly the Burning World, (New York, New York: Random House, 2022) p. xiii.

[51] Fears of a Setting Sun, pp. 218-221.

Loved it as usual. I really like the part about listening and not thinking about what you are going to say next. That is something I struggle with and have been working on the past while, still a lot of work I need to do in that area.

I actually should just call you because I heard something the other day I was curious your thoughts about. “Why does America still put so much stock in a document written over 200 years ago?” I think implying that we should have evolved past it by now. I just heard it and thought I wonder what Dad would say to that. I am not saying that.

Lastly there is only one point I would disagree on and that was with the negative points about social media you didn’t acknowledge the copious amounts of adorable pet videos are on these sites and how that makes everything better! 😄

I, too, struggle with the listening part. I preach a good sermon, but often fail to follow my own advice.

When people express a desire to jettison our Constitution, what they’re really complaining about is democracy and how terribly inefficient it is. But it is inefficient by design. It forces people to pause and reflect, debate and refine, and above all compromise.

In today’s world short of attention spans and instant gratification, people are impatient with democracy. The Israelites became impatient with a government built around a system of judges which they believed was not responding quickly enough to their needs and desires. So they threw it out in favor of a king. That didn’t work out too well for them.

You got me on pet videos. I deliberately ignored them because I’m envious of that chicken that can play the piano better than I can.

Very interesting stuff, Eric. One thing kind of off topic that I’ve been contemplating – I have so many clients and friends who have virtually “lost” their sons – who are living in the basement, addicted to video games, not thriving. The numbers of enrolled women versus men in universities – where are we headed in the future if this trend continues? How is it that so many young men are not contributing members of society? Is this only happening in my circle? And I realize that this topic only peripherally intersects with your article, but it’s really been on my mind. What is happening to the young men in this country (is this the same across other cultures)?

Thank you again for so much insight and research, and I too must start listening better.

Karen, I don’t think what you are experiencing is atypical and I believe it is, to some degree, symptomatic of the infantilization being perpetuated by so many of our institutions (including families), as I noted in my essay.

A record number of both young men and young women are living at home, but you’re correct: the numbers are notably higher for young men. Some of this is the result of helicopter parenting over the past twenty years, an issue discussed at length in Jonathan Haidt’s excellent book, “The Coddling of the American mind.” As to young men in particular, we have seen great emphasis on teaching young women they can “have it all” (which is a myth) to the point, perhaps, of failing to provide much-needed guidance to young men.

There was a time when young men were told it was their job to be the primary breadwinner in the home, but that message is no longer communicated with much frequency. While I think it’s wonderful that women are now encouraged to have a fulfilling career, marriage and family life, we haven’t replaced the traditional expectations for young men with something they can work towards, such as being a productive member of society and finding a spouse who will support you and that you can support.

You combine this with the trend of young people to delay marriage and starting the family, it’s little wonder that the maturation process is taking longer.

As I said, this is a complex issue, one where I do not profess to have much insight. But it is a serious.

Thanks, as always, for being a faithful readers.

What a superb essay! Those Tocqueville quotes are astonishingly prescient. I need to devote more careful attention to Tocqueville, whose works I’ve only skimmed.

Obviously, a lot of people are giving serious thought to the issue of why we appear to be unable to listen to those of our fellow Americans with whom we disagree. From Ezra Klein on the left (whose book “Why We’re Polarized” is very good) to Jonathan Rauch in the center (whose “The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth” is superb) to Jonah Goldberg on the right (whose “Suicide of the West” is also very good), the diagnosis of our issues is very similar to yours (though much less pithy and focused), as are their solutions.

The best political commentators who I follow — preeminently David French — are committed to construing the arguments of those they disagree with as “iron man” arguments, rather than “straw man” arguments. That is, they try to respond to the strongest version of opposing arguments, rather than trivializing them or distorting them. It is encouraging that there are quite a few prominent commentators today who recognize the problem and are committed to combatting it.

That said, my personal experience has not been encouraging. For about a year and a half, I was in an online book club formed by two Ph.D. psychologists, one a self-described progressive and the other a bit more centrist, for the express purpose of having civil and respectful discussions across political and ideological divides. The group blew apart when the progressive co-founder declared the whole project “too stressful,” while deriding a “straw man” version views of the libertarians and conservatives in the group. There is no one among my siblings or their spouses with whom I can have a civil conversation about politics. And I have not had an online political discussion about politics or policy issues since January 7, 2021.

Discussions seem pointless, since respect for the truth seems to have dramatically declined. To take only two examples (both extreme) — the factually baseless public assault on Brett Kavanaugh during his confirmation hearings (designed to destroy our judicial branch of government) and the big lie that Trump was cheated out of reelection in November (designed to destroy our executive branch of government — should be enough to make every American despair about whether truth actually matters any more.

I clung to a Madisonian optimism about the value of civil, fact-based discourse for many years, but at this point I can’t honestly claim that much optimism remains. The left and the right both seem irrevocably committed to destroying those they view as their enemies (aka “their fellow Americans”), with little or no concern for the future of our constitutional democracy.

Thoughtful well written piece. It certainly give me a lot to ponder. I appreciate your scholarship, thoughts, and attempt to put ideas into recipes for action. THANK YOU Karen

Great to hear from you, Karen. And thanks for taking the time to read this essay. It’s a bit longer than my usual fare, but, as you could see, I had a lot on my mind.

Hope you’re well.

Doug, thanks, as always, for your insightful (albeit somewhat disheartening) contribution. I’d like to be able to say that your current pessimism is unwarranted, but I would be dishonest if I did.

I, too, am a big fan of French and his ilk, but they seem to be a vanishing breed. But rest assured, I am always available to discuss politics with you—something I thoroughly enjoy because I invariably learn something in the process.