The reality of the first vision occurring precisely as described in the Pearl of Great Price is deeply ingrained—some would say, inculcated—in Mormon culture. Instructions given to church leaders and educators by Ezra Taft Benson on this point were unambiguous:

“You should always bear testimony to the truth of the First Vision. Joseph Smith did see the Father and the Son. They conversed with him as he said they did. Any leader who, without reservation, cannot declare his testimony that God and Jesus Christ appeared to Joseph Smith can never be a true leader, a true shepherd.”[1]

President Gordon B. Hinckley upped the ante when he unequivocally declared that, “Our whole strength rests on the validity of that [First] vision.” * * * “In all recorded religious history there is nothing to compare with it.”[2]

For those with doubts or questions about the First Vision, who cannot accept Joseph’s theophany on such strict terms, who are skeptical that everything transpired exactly as it is recorded in modern-day scripture, you are not alone. I, for one, believe Joseph saw only the Lord Jesus Christ 200 years ago. I do not believe he was subjected to a malevolent force when he prayed. I do not believe he asked the Lord which church was true. And I do not believe he was “hated or persecuted” for seeing a vision. And yet…

And yet, I believe the version of the First Vision found in the Pearl of Great Price is the one that belongs there. How I traveled from point A to point B is the subject of this essay.

While there are, by some estimates, around ten different accounts of the First Vision, there are four principal versions, each known by the year in which it was composed: (i) 1832, (ii) 1835, (iii) 1838/39, and (iv) 1842. The third of these—the 1838/39 Account—is the one accepted as scripture.

Marvin S. Hill, a BYU history professor, suggested we analyze the various accounts of the First Vision in the following manner: “It seems to me that everybody has approached the issue from the wrong end, by starting with the 1838 official version, when the account they should be considering is that of 1832. Merely on the face of it, the 1832 version stands a better chance of being more accurate….”[3] I agree.

The arguments in favor of the 1832 version—the one where Joseph: (i) saw only one personage, (ii) expressed no concern about which church to join since he had already decided that none was correct, (iii) was not subjected to an evil force, and (iv) is silent regarding subsequent persecution—are persuasive, in my opinion.

First, it is the earliest of all the accounts, though it was not written until twelve years after the event, so it too likely contains errors and omissions. Second, it is the only one written in Joseph’s own hand. Third, it was composed in response to a revelation he had received from God a couple of years before, instructing him to produce an accurate historical accounting of the events that made him a prophet.

Also, the spartan nature of this account corresponds with his stated reason for retiring to the Sacred Grove to pray: his only concern was for the status of his “immortal soul.” He was “exceedingly distressed, for I had become convicted of my sins, …” In other words, his sole purpose in reaching out to the Lord was to obtain forgiveness, which was granted. The only instruction he received was to keep the commandments.

This is entirely consistent with what the scriptures teach us regarding the manner in which God reveals his will to his children. Only rarely does the Lord take the initiative; rather, the supplicant must first “knock.” And the response given will typically deal solely with the question asked. It was only after Joseph made further petitions on other matters—and matured—that additional instruction was given, through the Angel Moroni and other heavenly messengers.

Also, Joseph’s experience—which he described as a “vision,” not a “visitation[4]”—was not unusual at that time. As noted by D. Michael Quinn, it was “similar to theophanies of other young seekers during the revivals in early America….”[5] Indeed, in the words of another scholar, the quandary at that time was “as much one of God’s loquacity as God’s hush.”[6] Thus, it was not an event so extraordinary as to have no contemporary or historical parallels.

So what accounts for the significant differences between Joseph’s first account and the one he produced about six years later? I believe the answer can be found by focusing on what Joseph learned and experienced during the interim.

At the time he wrote the 1832 account, Joseph embraced a variant of trinitariansim known as modalism: the belief that God and Christ are one and the same. Specifically, God was the Father in Old Testament times, but became the Son of God through incarnation.[7] This understanding of the Godhead was quite common in Joseph’s day.

You can see this in several of his early revelations, which blur the distinction between the Father and the Son.[8] Likewise, numerous passages in the first edition of the Book of Mormon imply that the two are one being, such as Ether 3:14: “Behold, I am Jesus Christ. I am the Father and the Son.” And note the change he made to Luke 10:22 in the early 1830s. The original reads: “… no man knoweth who the Son is, but the Father; and who the Father is, but the Son,…” But in Joseph’s version, Jesus declares that “no man knoweth that the Son is the Father, and the Father is the Son,…”

Around 1834, however, something began to change. In the Lectures on Faith delivered at the School of the Prophets, the Godhead is described as consisting of two personages: the Father and the Son. There is also evidence that in 1834, when he began to publicly discuss the First Vision, he mentioned a conversation he had had with both the Father and the Son. This was followed by his dictated diary entry in 1835—the second of the four major accounts—where he mentions seeing two personages. His theology of the Godhead was evolving.

What we see is often a byproduct of what we expect to see. Thus, I believe Joseph, consistent with his limited understanding of the Godhead and his expectations when he entered the woods to pray, saw only one divine being, as recorded in his 1832 account. But what the prophet subsequently learned through prayer, study, and further revelation, altered his understanding. This, in turn, prompted him to revise several verses in the Book of Mormon, changes incorporated in the book’s second edition published in 1837. A couple of examples:

1st Ed.: Behold , the Lamb of God, yea, even the Eternal Father!

2nd Ed.: Behold, the Lamb of God, yea even the Son of the Eternal Father! (Nephi 11:21)

1st Ed.: …yea, the everlasting God was judged of the world…

2nd Ed.: …yea, the Son of the everlasting God was judged of the world… (Nephi11:32)

So, just as Joseph’s evolving understanding of the nature of the Father and Son caused him to rethink the inspiration he received while translating the Book of Mormon, so, too, did it serve as a catalyst for his reimagining what he experienced in the Sacred Grove.[9]

But what are we to make of Joseph’s assertion in the 1838-39 account that his theophany precipitated “a great deal of prejudice against me among professors of religion and was the cause of great persecution which continued to increase” until “all the sects united to persecute me.”[10]? This is completely at odds with the historical record. There is no evidence he told anyone about his experience for ten years, save a lone Methodist minister.[11] And if he had shared it with others, it is improbable that most people—especially professors of religion—would have considered a 14-year old kid a threat to the status quo.

According to Steven C. Harper, professor of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University, it appears the prophet was projecting the persecution he experienced in 1838—one of the most difficult times of his life—back onto the First Vision.[12]

During that period he was accused and acquitted of murder. Then there was the economic crisis in Kirtland, Ohio, precipitated by his ill-advised banking scheme, which prompted a number of his closest associates to turn on him and try to replace him. Threatened with lawsuits and violence, Joseph fled in the dark of night to Far West, Missouri. But conditions there were not much better and were about to get worse. In November of that year he was arrested for treason and incarcerated in Liberty Jail, where he endured some of the darkest hours of his mortal existence. Little wonder that this would color his 1838/39 account of the First Vision.

Science has shown that our memories are both fallible and malleable, especially when it comes to the most pivotal moments in our lives. We mold our recollection of those events to make sense of what we have learned and what we are experiencing in the present moment. This is a critical evolutionary survival mechanism.[13]

The purpose of our memory is not photographic recollection, but to learn and to teach. Indeed, a perfect and permanent recall of everything that ever transpired in our lives would be a nightmare, impeding our efforts to assimilate past experiences and give them new meaning through the prism of acquired wisdom.[14]

The temptation to harmonize the First Vision accounts is usually driven by a desire to protect the saga from appearing disjointed or ad hoc, one borne by the belief that a lack of uniformity among accounts is indicative of a lack of truth. Joseph Smith didn’t think this was necessary because he grasped the critical difference between his 1832 account and the one in the Pearl of Great Price: The former was a descriptive history written at God’s command. The latter, by contrast, reflects a combination of his personal interaction with the divine, additional light and knowledge acquired through study and contemplation, and personal experiences, especially those involving persecution. And had he lived longer, Joseph might have had further insights, adding a Mother in Heaven, perhaps—the parents of our Savior joining together to say: “This is Our Beloved Son. Hear Him!”

I find the foregoing a much more compelling explanation for the canonized version of the First Vision because it is a product of inspiration and Joseph’s spiritual growth, not the supernatural (i.e., that 18 years after the event, God suddenly brings to Joseph’s mind a perfect recollection of what transpired in the Sacred Grove). Interestingly, the authors of the First Vision essay on LDS.org seem to agree: “Joseph’s increasingly specific descriptions can thus be compellingly read as evidence of increasing insight, accumulating over time, based on experience.”[15]

In addition to being a prophet, Joseph Smith was an iconoclast, a visionary, and a theological genius. But his genius, if I may borrow from Proust,

[Sprang] less from the seeds of intellect and social refinement superior to those of other people than from the faculty of transforming and transposing them. * * * [He did not] live in the most delicate atmosphere, [his] conversation [was not] the most brilliant [nor his] culture the most extensive, but [he] had the power, ceasing suddenly to live for [himself], to transform [his] personality into a sort of mirror, in such a way that [his] life, however mediocre it may be socially and even, in a sense, intellectually, is reflected by it, genius consisting in reflecting power and not in the intrinsic quality of the scene reflected.

Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, Vol. 2: Within a Budding Grove, (The Folio Society: London, 1992), pp. 121-122.

[1] Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson, p. 101; “Church History in the Fullness of Times Teacher Manual.

[2] Hinckley, Gordon B., “The Marvelous Foundation of Our Faith,” LDS General Conference, October 2002.

[3] Marvin S. Hill, “The First Vision Controversy: A Critique and Reconciliation,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Summer 1982), pp. 31-46.

[4] Joseph Smith, “Letter to John Wentworth,” Publisher of the Chicago Democrat, Times and Seasons, Vol. 3, pp. 706-710 (March 1, 1842) (“My mind was taken away from the objects with which I was surrounded, and I was enwrapped in a heavenly vision.”).

[5] D. Michael Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magic World View, 2nd ed., revised and enlarged (Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 2009, p. 137).

[6] Leigh Eric Schmidt, Hearing Things: Religion, Illusion, and the American Enlightenment, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2002), p. 11.

[7] Charles R. Harrell, “This Is My Doctrine,” (Sandy Utah: Greg Kofford Books, 2011), pp. 160-161.

[8] D&C 20:28; 11:2, 10, 28; 49:5, 28.

[9] Matthew L. Harris and Newell G. Bringhurst, eds., The LDS Gospel Topics Series: A Scholarly Engagement, David J. Howlett, “The Cultural Work of the ‘First Vision Accounts’ Essay, (Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 2020), p. 148.

[10] Joseph Smith—History 1:22.

[11] Steven C. Harper, First Vision: Memory and Mormon Origins, (Oxford University Press: New York, 2019), pp.9-11, 18, 51. Joseph shared with his father the details of his first visit from the Angel Moroni in 1823, but there is no evidence in the journals of any family member or any other source that he discussed the First Vision with anyone until 1830, save a lone Methodist minister.

[12] Ibid, pp. 16-19, 40.

[13] Michael D. Lemonick, “When Our Memories Are Both Vivid and Wrong,” Wall Street Journal, January 28, 2017.

[14] Memory and Mormon Origins, p. 38; see also, A. R. Luria, The Mind of a Mnemonist: A Little Book About a Vast Memory, Lynn Solataroff, translator, (New York: Basic Books, 1968).

[15] “First Vision Accounts,” November 2013.

This is a great article. Thank you for writing it. I had never heard the different stories of the 1st Vision. I feel the same as you about my testimony of that event.

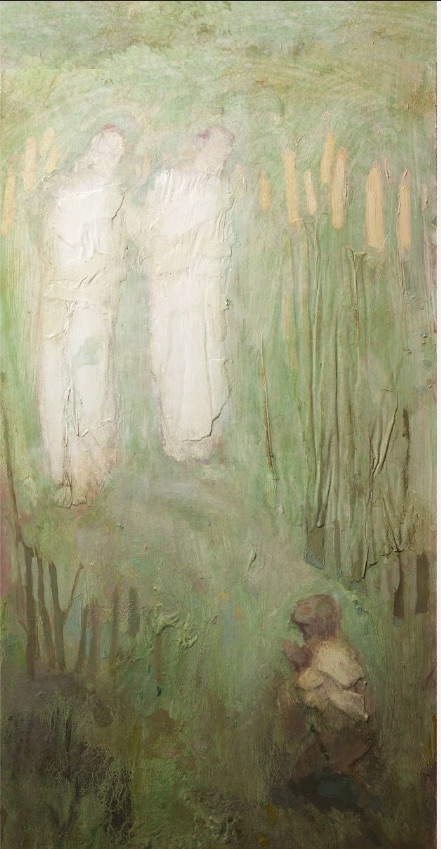

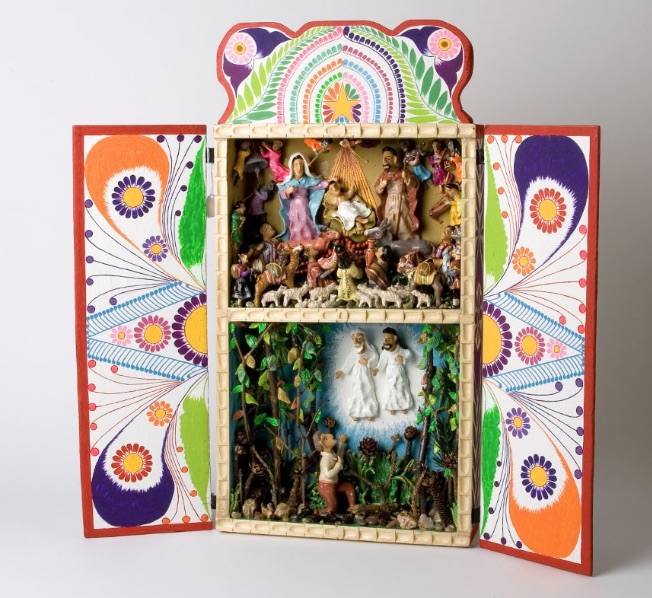

It was fun to see the picture of that sculpture. I have that sculpture of the First Vision in my home. My first companion on my mission ( Kraig Varner) sculpted it. And another friend of mine, Lee Snarr, (also on my mission) was the one who came up with the idea of the sculpture and pitched the idea to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints and to Kraig. He also helped Kraig during the sculpting process of having it made. Then sold the second of fifty made to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Saints and it was placed in the Hall of the Prophets in the Conference Center. Thanks again Chris

That’s a terrific story, Chris. Thanks so much for passing it along. I find that images often communicate ideas and perceptions I am unable to express in words. Learning about your connection to one of them is a bonus.

By the way, I would have included a caption under the image of the sculpture, noting Kraig as the artist, by the WordPress web design program I use only permits captions on stand alone, or side-by-side, pictures. I need to find a workaround for that.

“Science has shown that our memories are both fallible and malleable, especially when it comes to the most pivotal moments in our lives. We mold our recollection of those events to make sense of what we have learned and what we are experiencing in the present moment. This is a critical evolutionary survival mechanism.”

I have my own experience with this phenomenon. For the last 16 years I’ve told “the story” of how we named our oldest child countless times. I feel like I have a perfect memory of how events transpired. But I also keep a daily journal. And when I re-read the entries leading up to her birth, they tell a very different story. The timeline is different and key details differ greatly from what I remember. Which is correct? What I wrote with my own hand 16 years ago? Or what a remember today so vividly? There is a part of me that is inclined to think I “wrote it wrong” I’m so convinced of my own memory. This experience has given me a new perspective on how I receive anyone’s recollections after the fact and especially years and years later. Even my own.

Well said, S. Barnhart. While disorienting, experiences like the one you describe serve to both instill humility regarding our own recollections and skepticism regarding those who claim to have vivid recall of events that transpired years ago.