This is a story about a planet called Vulcan. No, not the place where S’chn T’gai Spock—better known as “Mr. Spock”—was raised by his Vulcan father and human mother. This is about a planet in our Solar System by that very same name. It differs, however, from all the rest in one important respect: no one has ever been able to find it.

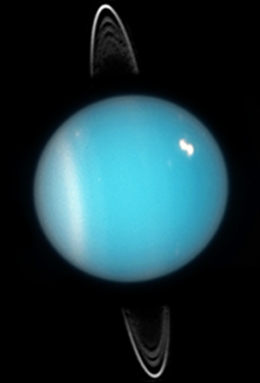

To understand the mystery of Vulcan and how it was eventually solved, we must first turn our attention to a different—and quite real—planetary body: Uranus. While Uranus was discovered towards the end of the 18thcentury, during the early 1800s astronomers were beginning to wonder whether it might actually be a star. Those doubts had arisen because the planet was not adhering to Newton’s theory of gravity.

Among other things, his theory postulated that the precise location of a planet, at any moment in time, can be predicted provided all significant gravitational effects—those produced by the Sun and neighboring planets—are accounted for. But when the corresponding mathematical calculations were performed for Uranus, it wasn’t where it was supposed to be. It was close, but no cigar.

Enter the French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier, who hypothesized the existence of another planet, one further away from the Sun and large enough to wield sufficient gravitational pull to cause the anomaly in the orbit of Uranus. Devising this theory and expressing it mathematically was devilishly difficult. But once he completed the process and astronomers turned their telescopes to the point in the sky dictated by the result, voilà: there sat Neptune. Brilliant!

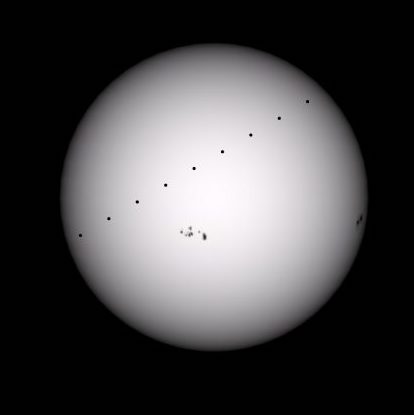

As it turns out, Uranus was not the only planet whose orbit was out of kilter. Le Verrier and others noticed that Mercury, whenever it transited the face of the Sun, began the process approximately 16 seconds later than Newton’s theory dictated. This was not a lot, but in astronomical terms it was significant. And with the recent discovery of Neptune, a logical explanation was readily available: an unidentified planetary body, somewhere between Mercury and the Sun, was exerting its influence. All we had to do is find it.

Armed with Le Verrier’s equations and ever more powerful telescopes the game was afoot. So confident were these planetary detectives in their ability to trap their quarry, they gave it a name: Vulcan.

Sightings of this celestial Sasquatch were frequently reported, but the creature always slipped into the night before anyone could confirm its existence. Towards the end of the 19th century, after decades of searching, the quest was abandoned. Nevertheless, a few remained troubled by Mercury’s unexplained behavior, including a Class III technical expert working for the Swiss patent office.

He struggled with this conundrum for years. By the time he devised a solution he was a physics professor at the University of Berlin and had published a number of important scientific articles, including a groundbreaking paper on quantum theory that would eventually yield a Nobel Prize.

But Albert Einstein’s explanation for Mercury’s behavior was radical. It didn’t simply account for a sixteen-second delay in Mercury’s orbit about the Sun; it completely upended the current understanding of the universe.

In simple terms, Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, which builds on his Special Theory of Relativity published ten years earlier, posits a universe with a fourth dimension: time, which he called “space-time.” Working with his friend and former math teacher, Herman Minkowski, Einstein predicted that the gravity of massive objects, like the Sun, was so strong it actually warped the space around them, bending and deflecting a ray of light passing through its gravitational field. Mercury’s aberrant behavior could be explained by this distortion in the space-time continuum.[1]

This discovery—one that not only solved a specific mystery but also reimagined the entire cosmos—was worked out by Einstein between his ears and on paper with his pen. When he hit upon the solution, he told a friend, his heart actually shuddered in his chest and he was “beside himself with joy.”[2]

This wasn’t simply a matter of thinking outside the box; rather, it required true genius, something that is exceedingly rare. As the German philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer, explained, men and women of learning, of which there are many, are simply those who have learned a great deal. But a genius is “one from whom we learn something which the genius has learned from nobody.”[3]

True genius requires many things, including constant seeking and questioning—challenging not just existing beliefs and practices but the actual assumptions on which those beliefs and practices are based. Socrates actually made this his life’s work. According to one historian, “he went about prying into the human soul, uncovering assumptions and questioning certainties.”[4]

Abraham Lincoln did this in the way he asked his fellow citizens to reimagine a world without slavery. Some scholars believe Lincoln’s feelings about slavery originated in his childhood, when he experienced extreme poverty and indentured servitude at the hands of his father. In his day, that form of servitude was sometimes called thrall. Later, when he was President, he would use the word disenthrall to convey the importance of approaching the nation’s crisis with a completely new perspective. In a message to Congress, he said, “As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew.” He then added, “We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”[5]

A true genius, however, must be willing to question not only the assumptions and certainties of others, but also his own. This is difficult for all of us, especially when it comes to our religious convictions, which everyone, regardless of their faith tradition, believes are true and are better or just as good as those of the guy next door.

Gordon B. Hinckley, when extending an invitation to those not of the Mormon faith, expressed his appreciation for the truth in all churches and the good they do, and then said: “We say to the people, in effect, you bring with you all the good that you have, and then let us see if we can add to it. That is the spirit of this work.” Though I doubt this was Hinckley’s intent, his invitation could easily be perceived by someone of a different faith as condescending. Missing is any notion that other churches are in possession of truths that have been overlooked by the Mormon faith, that other religions have something to teach Latter-day Saints about the gospel and doing good in the world. This mindset can breed arrogance and inhibit the acquisition of knowledge.

But on another occasion, Hinckley said: “I confess that I am constantly appalled by the scarcity of my knowledge, …”[6] This coming from a man who was extremely well-read and able to cite long passages of Shakespeare’s plays from memory his entire life. Such humility creates fertile ground where genius can often germinate.

An unwillingness to examine our own beliefs and resistance to new ideas is a form of pride that can deceive even geniuses, including Albert Einstein. Although he helped pioneer the field of quantum mechanics, he could not accept certain elements of that theory. The notion of a probabilistic universe built on the unpredictable behavior of subatomic particles—such as, pairs of photons linked even when hundreds of miles apart (“entanglement) and objects whose condition can be altered by the mere act of observation (Schrodinger’s cat)—was something he could not abide. Though the mystery of quantum mechanics has yet to be fully solved, without it, we would be unable to produce laser beams and build the integrated circuits required by our computers and smartphones.

Perhaps one of the greatest impediments to our discovery of new truths is our unwillingness to accept the unpredictability and paradox inherent in our existence. And we tend to pass over such incongruities when we study the scriptures and our history, settling instead for glittering generalities and theological Twinkies,[7] or convoluted explanations that smooth off the rough edges and harmonize what we encounter.

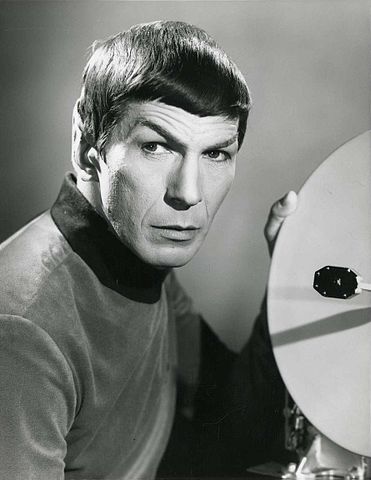

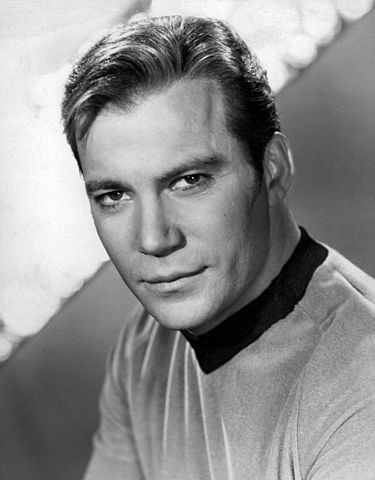

Because we often neglect to “puzzle and puzzle ’till our puzzlers are sore,” we miss many of the truths found in the scriptures and fail to learn that each of us, at some point in our lives, will likely be forced to choose between two unpleasant courses of action, just as the Savior did with the atonement. Mr. Spock, and his mentor Admiral James T. Kirk, understood this all too well. For that reason, they required Starfleet cadets to undergo the Kobayashi Maru training exercise, one designed to test their character by forcing them to confront an insurmountable scenario gracefully.

As we complete our elliptical tale, we find that “Vulcan” turned out to be the correct name for the celestial body distorting the orbit of Mercury. For Vulcan was the Roman God of Fire, the God of the Furnace, the place where the Sun, and other stars like it, forge the elements of the universe. And coincidentally, the Roman God Mercury was, among other things, a God of Messages, who, 105 years ago, delivered a short epistle to a former Swiss patent technician: “You have uncovered another of our secrets, but you’ve only scratched the surface.”

[1] Thomas Levenson, The Hunt for Vulcan, (New York: Random House, 2015), pp. 170-72.

[2] Ibid, p. 173.

[3] Joseph Epstein, The Ideal of Culture, (Edinburg, Virginia: 2018), pp. 57-58.

[4] Will Durant, The Story of Philosophy, (New York: Simon & Schuster: 1961), p. 9.

[5] Ted Widmer, Lincoln on the Verge, (New York: Simon & Schuster: 2020), p. 93.

[6] Scott C. Esplin (Author, Editor) and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel (Author, Editor), The Voice of My Servants, (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book 2010), p. 61.

[7] Jeffrey R. Holland, “A Teacher Come from God,” Report of the April 1998 General Conference. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

I’ve said it before but not everyone can work in Star Trek, Albert Einstein, Schrodinger’s cat and the Grinch into the same article. Well done!

What might have made for an interesting discussion is that Captain Kirk cheated to win the Kobayashi Maru exercise. Maybe not graceful but definitely effective.

Thorpe, I believe my ability to weave together so many disparate—and peculiar—sources is traceable to a head injury I suffered when I was young. As to Captain Kirk and the Kobayashi Maru exercise, I’m confident that I, too, had I been in his position, would have cheated and been proud of it!

This makes me sad to think of all the genius that has been squashed by a world that highly values rote memorization and uniformity over curiosity, independent thought, and questioning the status quo. You almost have to be genius AND a rebel to bring about new and better ideas. And I don’t think genius is a personality type. There are a lot of submissive, pleaser-personalities that have amazing ideas but will never speak up lest they be castigated like some of the geniuses you wrote about.

Also, as far as the Kobyashi goes, I think that cheating is genius in this situation. When we are faced with the impossible, its time to break the rules!

S Barnhart, I concur wholeheartedly. Whenever the status quo is threatened, in science, religion, politics or any other field, its defenders will man the ramparts and do their best to intimidate—even threaten and attack, if necessary—the challenger. It takes courage to persevere in the face of such opposition.

During my freshman year in college I studied musical composition, where I learned, among other things, the rules that give structure to particular forms of music, such as the sonata, the waltz, the trio and the symphony. And certain things—e.g., parallel fifths—I was told are forbidden. But I’ll never forget a lesson I was taught by one of my professors: the truly great composers analyze and master these rules of composition—and then proceed to break one or more of them. Otherwise, the art form could not progress.

Perhaps the one composer who understood this principle better then most was Beethoven, whose late string quartets were so unconventional that the acclaimed Italian violinist, Felix Radicati, complained that they were “not music.” The composer responded: “Oh, they are not for you, but for a later age.” His words were prophetic, for these are regarded today as among Beethoven’s masterworks.

Coincidentally, this year marks the 250th anniversary of the master’s birth. Those whose cultural education was not neglected by their parents and therefore were exposed to the early texts of a true American genius, Charles M. Schultz, the creator of “Peanuts,” know that the December 16th edition of that comic strip always featured Schroeder at his piano paying homage to his beloved hero on the day of his birth.

I love this comment and never knew you studied musical composition. How interesting. Do you ever still create your own compositions? I’d love to hear one.

Karen, I haven’t composed in a while, but I do frequently arrange pieces, which I often do when I perform in church, especially at Christmas time. Perhaps some day I’ll dig out some of my old work and play it for you, though it isn’t very good.

I thoroughly enjoyed my time studying music in college. And while I did well in the course work, I soon realized that most of my peers had considerably more talent, so I chose a different career path.