Seventy-six years ago this morning, the United States and its allies launched the largest amphibious invasion in history when they attacked German forces occupying Normandy along the northern coast of France. The invasion—which came to be known as “D-Day”—consisted of approximately 7,000 vessels, 1,200 of which were warships. But most were transport vessels tasked with landing 150,000 allied soldiers and their equipment on five beaches—code-named Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword—spanning some fifty miles.

The attack was preceded by an immense aerial and naval bombardment of the Normandy coast. Allied planes dropped more than 11,000 tons of bombs in the eight hours prior to the invasion, while the fleet’s artillery pounded the coast just before the troops went ashore. In 10 minutes, 600 naval guns fired 2,000 tons of shells at various German fortifications.

Before the barrage began, a German soldier manning a gun emplacement saw the armada stretched before him and later said: “I was struck  speechless at the sight, which I had never imagined possible. * * * Even as I stared, more ships came into view, endlessly filling the sea. I remember, if I may be honest, that I began to tremble, and I broke out into a sweat.” One of his companions looked at him and said, in bitter fashion: “Are we sorry we started this war now?”[1]

speechless at the sight, which I had never imagined possible. * * * Even as I stared, more ships came into view, endlessly filling the sea. I remember, if I may be honest, that I began to tremble, and I broke out into a sweat.” One of his companions looked at him and said, in bitter fashion: “Are we sorry we started this war now?”[1]

While the pre-dawn bombing and shelling noticeably weakened the German defenses at four of the beaches, the allied planes and ships missed virtually all of their assigned targets at Omaha, leaving the first two waves completely exposed to withering fire. Their misery was compounded by the decision to invade at low tide, which was done so that the obstacles installed by the Germans to impede landing craft and tanks would be visible. This greatly increased the amount of open ground the infantry, heavy-laden with equipment, was required to traverse.

One private later wrote: “There were men crying with fear, men defecating themselves. I lay there with some others, too petrified to move. No one was doing anything except lay there. It was like a mass paralysis. I couldn’t see an officer. At one point something hit me on the arm. I thought I had taken a bullet. It was somebody’s hand, taken clean off by something. It was too much.”[2]

A member of a neighboring battalion recalled seeing his devout sergeant, “Pilgrim” Robertson, with a gaping wound in his forehead. “He was walking crazily in the water without his helmet. Then I saw him get down on his knees and start praying with his rosary beads. At this moment the Germans cut him in half with their deadly crossfire.”[3]

For the better part of the morning, Omaha Beach had the makings of a disaster. If the allies were thrown back into the sea, then Utah Beach to the west on the Cherbourg Peninsula would be completely isolated and Gold Beach to the east would be exposed to a flank attack by German reinforcements. It was only after several small, but very determined, groups of men—most notably the Army Rangers—managed to scale the bluffs above the sea and root out the entrenched defenders that the tide began to turn.[4]

In October of 2018, we spent three days roaming the beaches and battlefields of Normandy to gain a greater understanding of what transpired there on that fateful day. We began with a tour of the Caen Memorial Museum, which has one of the finest collections of World War II artifacts, memorabilia, and exhibits in the world.

We also stopped at Pegasus Bridge, site of a daring night landing by three large gliders during the early morning hours of D-Day. Led by Major John Howard, a British military officer, a force of 181 men prevented the Germans from demolishing a critical passageway to the interior of Normandy. Their exploits were later immortalized in the classic World War II movie, The Longest Day.

Howard, a British military officer, a force of 181 men prevented the Germans from demolishing a critical passageway to the interior of Normandy. Their exploits were later immortalized in the classic World War II movie, The Longest Day.

Still standing on one side of the bridge is Café Gondrée, which is owned by Arlette Gondrée, who was five-years old at the time of the liberation. She is an irascible old woman, we discovered, who doesn’t like making small talk with patrons.

Arlette Gondrée, who was five-years old at the time of the liberation. She is an irascible old woman, we discovered, who doesn’t like making small talk with patrons.

Many of the residents of Normandy we encountered expressed their gratitude for the American GI’s who liberated their country. And I was quick to acknowledge that but for the financial and naval support provided by Louis the XVI, the American colonists likely would have lost the Revolutionary War.

Even though allied bombs unintentionally destroyed hundreds of homes and killed thousands of innocent French civilians, most residents understood that such “collateral damage” was a sacrifice they had to make in order to expel the Germans. Still, the experience of that conflict left an indelible impression on the psyche of the local residents we were  told. Drawings by school children we saw on display inside a nearby French church suggest that peace has a deeper, intergenerational meaning for people who have experienced firsthand the horrors of war.

told. Drawings by school children we saw on display inside a nearby French church suggest that peace has a deeper, intergenerational meaning for people who have experienced firsthand the horrors of war.

One afternoon we toured the  remnants of a small German anti-aircraft gun operation set in the woods a mile or so from the beach. It sits on private land owned by a local Frenchman who frequently leases it to film studios. He sometimes makes his own battle reenactment videos, which he uses to

remnants of a small German anti-aircraft gun operation set in the woods a mile or so from the beach. It sits on private land owned by a local Frenchman who frequently leases it to film studios. He sometimes makes his own battle reenactment videos, which he uses to  market the location. Obtaining volunteers to play the parts of American and British fighters, along with members of the a French resistance, is easy. But he has to pay people to don a German uniform.

market the location. Obtaining volunteers to play the parts of American and British fighters, along with members of the a French resistance, is easy. But he has to pay people to don a German uniform.

One of the most indelible memories of our visit occurred when I walked  one morning to the water’s edge at Omaha Beach during low tide—and then turned around. How any man could have mustered the courage to cross that expanse with the fires of hell raging on all sides is beyond my imagination.

one morning to the water’s edge at Omaha Beach during low tide—and then turned around. How any man could have mustered the courage to cross that expanse with the fires of hell raging on all sides is beyond my imagination.

But what moved us most of all was the cemeteries.

Late one afternoon, as sunlight began to recede, we visited the Ranville  War Cemetery in Normandy, which is the final resting place for approximately 2,500 British soldiers. It is adjacent to the village

War Cemetery in Normandy, which is the final resting place for approximately 2,500 British soldiers. It is adjacent to the village  church, and set against the stonewall surrounding the churchyard are approximately 50 British graves, one of which is for an unknown soldier.

church, and set against the stonewall surrounding the churchyard are approximately 50 British graves, one of which is for an unknown soldier.

It is also where Private Robert Johns, a member of the 13th Parachute Battalion, is interred. He was only 16 when a sniper’s bullet took his life. His epitaph at the base of his tombstone reads: “He died as he lived, fearlessly.”

It is also where Private Robert Johns, a member of the 13th Parachute Battalion, is interred. He was only 16 when a sniper’s bullet took his life. His epitaph at the base of his tombstone reads: “He died as he lived, fearlessly.”

This site was chosen—along with the location of most other British cemeteries in Europe—for one simple reason: it is where most of these men died. For this reason, there are dozens of British military cemeteries scattered across Europe. The English buried their men where they fell. American cemeteries, by contrast, are fewer in number but larger in size.

British burial grounds also differ from their U.S. counterparts in one other respect: they include soldiers from other nations—including Germans, over three hundred of which are buried in Ranville. Some of them, according to our guide, were members of an SS unit.

Somewhat to the surprise of our guide, I asked to see the La Cambe German War Cemetery, which is located not too far from Omaha beach. It is home to over 21,000 German war dead and is maintained by the German War Graves Commission.

German War Cemetery, which is located not too far from Omaha beach. It is home to over 21,000 German war dead and is maintained by the German War Graves Commission.

There are few crosses or traditional headstones in this cemetery; instead, the  burial place of most soldiers is marked with dark-colored plaques above their graves. The names of two soldiers are inscribed on each one, with one man buried on top of the other.

burial place of most soldiers is marked with dark-colored plaques above their graves. The names of two soldiers are inscribed on each one, with one man buried on top of the other.

We did notice a handful of German tourists during our stay in Normandy, many of whom, I suspect, were descendants of those who served in the Wehrmacht. It is tempting to disparage everyone who fought for Hitler’s war machine, but most were not members of the Nazi party and many were young men who had a patriotic desire to defend their country or were given no choice in the matter. And some were not German at all; they were Russian and Polish POWs who opted to fight in Normandy rather than endure the hardships of the camps (they were among the first to surrender to the allies, by the way).

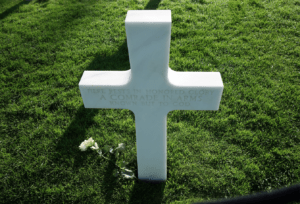

Without a doubt, the most memorable part of the trip for me was an early-morning visit to the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial. Here lie the dead of over 9,300 U.S. servicemen, along with four servicewomen, two of whom were of African-American descent.

lie the dead of over 9,300 U.S. servicemen, along with four servicewomen, two of whom were of African-American descent.

The cemetery, consisting of 172 immaculately groomed acres, is situated  on a bluff overlooking Omaha Beach. The moment you arrive, you know you are standing upon hallowed ground.

on a bluff overlooking Omaha Beach. The moment you arrive, you know you are standing upon hallowed ground.

We saw the plot of Brigadier General and Medal of Honor recipient  Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., son of our 26th President. And then there were the graves of the Niland brothers, one killed on D-Day, the other 24 hours later. They were two of four brothers all of whom saw combat during the Second World War and were the inspiration for Spielberg’s award-winning film, Saving Private Ryan.

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., son of our 26th President. And then there were the graves of the Niland brothers, one killed on D-Day, the other 24 hours later. They were two of four brothers all of whom saw combat during the Second World War and were the inspiration for Spielberg’s award-winning film, Saving Private Ryan.

The first time I passed a cross marked, “A Comrade In Arms Known but to God,” I paused for a moment and imagined the distress likely experienced by the man’s family who knew only that their son, grandson, nephew, or perhaps husband, was

The first time I passed a cross marked, “A Comrade In Arms Known but to God,” I paused for a moment and imagined the distress likely experienced by the man’s family who knew only that their son, grandson, nephew, or perhaps husband, was  “missing in action.” And it brought me up short when I first saw a soldier whose date of death was June 6, 1944. But the most moving experience of the day was a product of fate, serendipity, or divine intervention, depending upon your perspective.

“missing in action.” And it brought me up short when I first saw a soldier whose date of death was June 6, 1944. But the most moving experience of the day was a product of fate, serendipity, or divine intervention, depending upon your perspective.

Seeking greater solitude, I made my way to the rear  of the cemetery where I spied a small private gathering around a grave bordered on one side by a small American flag and, on the other, by the tricolor of France. The party was in the process of dispersing, and a cemetery maintenance worker was waiting for them to take their leave so he could continue his work. When I asked him who they were, he said they were related to the deceased soldier whose grave I had noticed. They had made special arrangements for a private commemorative service that morning.

of the cemetery where I spied a small private gathering around a grave bordered on one side by a small American flag and, on the other, by the tricolor of France. The party was in the process of dispersing, and a cemetery maintenance worker was waiting for them to take their leave so he could continue his work. When I asked him who they were, he said they were related to the deceased soldier whose grave I had noticed. They had made special arrangements for a private commemorative service that morning.

I then quietly approached the grave. Though the man’s name was not one I recognized, his date of death caught my eye—July 28, 1944—the same day and month on which I was born nine years later. I suddenly felt a desire to learn more about this soldier, so, giving little thought to how my intrusive behavior would be received, I approached the couple that had come to pay their respects.

The gentleman, who graciously indulged my curiosity, said the deceased, Sergeant Erling C. Olsen, was a member of the U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps. He was also the gentleman’s uncle. He was on a mission behind enemy lines when he was killed eight weeks after D-Day. His nephew was trying to learn more about his fallen relative, but much of the information about the CIC is apparently still classified. (The gold lettering on Sergeant Olsen’s gravestone, he told me, was produced by rubbing the inscription with sand from Omaha Beach.)

He said he felt a close bond with his uncle since he was born precisely two years later on the same day his uncle died. I smiled, and said: “I, too, was born on that day seven years after you.” His wife, who had been silent until then, asked, “Where do you live?” I responded: “In Clarendon, Virginia, less than a mile, as the crow flies, from Arlington National Cemetery.” At this she became somewhat emotional and withdrew. Her husband explained: “We live just a few miles from you in Burke, Virginia.” I didn’t know what else to say.

In Second Timothy, Chapter 4, we are told that Christ, “at his appearing and his kingdom,” shall judge “the quick [the living] and the dead.” Having seen the beaches and battlegrounds of Normandy, I can’t help but wonder how the soldiers who gave their lives during the Second World War—that freedom might be given yet another chance—would want to be measured and remembered? Earlier this week, while watching “The War,” an outstanding documentary about World War II produced by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, I found the answer in this this four-minute tribute to some of the members of The Greatest Generation.

Think Not Only Upon Their Passing

Remember the Glory Of Their Spirit

[1] Eckhertz, Holger, D Day Through German Eyes, Create Space Publishing, 2016, pp. 70-71.

[2] Hastings, Max, Inferno: The World at War, 1939-1945, Alfred A. Knopf, 2011, p. 517.

[3] Beevor, Anthony, D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, Viking Penguin, 2009, p. 95.

WOW! What a powerful story powerfully told. I to have experienced the overwhelming emotion of visiting Normandy. My Dad came into Utah beach a week or so after the D-Day invasion. I was born in 1943 so I was just 11 days shy of 1 year old when it happened. One of my parents best friends died in the bloody attempt to scale Pointe du Hoc on D Day. It is hard to visit this part of France and not become breathless knowing the intense drama and loss of life that happened here while children of God, so foolishly and violently, fought their spiritual brothers and sisters. There are so many deep tragedies of human existence. I hope they teach us all something and indelibly brings home the essential nature of Christ’s teachings built on non judgemental love and forgiveness.

Thank you Eric for your very moving post on this day commemorating “Operation Overlord”. Bruce and I visited Normandy two years ago around the anniversary of this historical event. We found the French in the countryside to be so very appreciative of the allies that liberated them from the tyranny of German occupation. We had the same spiritual experience as you did visiting the immaculately maintained American cemetery in Normandy. I think every American would benefit from a visit to Normandy to see what a dear price has been paid that we and others like us can live free! Reading books and watching

movies about this event do not begin to tell the story of the enormity of the challenges associated with this invasion. I am certain there was divine intervention helping peace loving nations to join together turning the tide of the war in favor of the allies. May we never forget.

Brought me to tears. Thanks Dad.

Thank you Karen and Linda, as always, for your insightful observations and comments. You both bring experience, knowledge and understanding to every discussion, something that occurs all too infrequently in today’s world.

Eric

I really appreciate you sharing this emotional experience you and Margaret had on your trip to Normandy. Missie and I would have loved to have been there with you guys. Missies uncles were part of WWII as a marine and naval fighter pilot. We have heard a lot of their amazing stories. What a well written article.

Thanks Chris

Thank you, Eric. Each generation is a little more removed from the reality of war and the sacrifice of so many individual men and women. It is a great blessing to not know personally the great deprivations of war. Still, I will never understand it in the same way as someone who has had to live though the sheer terrors of the battlefield. I am grateful this day and everyday for my freedoms, won through the sweat, tears and blood of so many others.

Very powerful and moving. Thank you for sharing this experience, Eric.

A fantastic article. While I am sure it paled in comparison, CG and I toured a military cemetery near Sarasota, FL about 4 years ago. The feeling which came over me at that location is like nothing else I have felt – simply a distinct feeling I was not alone, if you will. One headstone which I will always remember was that of a fallen hero and underneath his name it merely said: “A teller of tales.” Lives lost way too soon.

Chris, Virginia, Daniel & Andy,

Thank you all for your kind words and for taking the time to read my musings about my experiences in Normandy. Most of all I want to thank you for sharing similar experiences you have had and telling me about the service rendered by many of your family members during the Second World War.

As Andy knows, our father served in the Army Air Corps and was assigned to the Pacific Theatre, so he was the catalyst for our abiding interest in the war. I remember taking him to the World War II Memorial on the National Mall shortly after it opened. He was in my thoughts the entire time I wrote this essay.

I really enjoyed this, Eric. Thanks for sharing.

You’re quite welcome, Steve. I had been meaning to put some of these experiences on (virtual) paper before they escaped my memory. I’m glad the stars aligned in such a way for me to do so.

Eric,

Thanks so much for this. Ashlee and I were in Normandy last October and a few years before that we toured all through Luxembourg and Belgium to see the Battle of the Bulge sites, including the beautiful military cemetery in Luxembourg City (where Patton is buried). I have in my office a small branch from the woods outside Bastogne and shells and sand from Omaha Beach – constant reminders of the sacrifices others made for me and the duty I have to pass their memories and legacy on.

We toured through Belgium and Luxembourg with my parents who were at the time serving a mission in Frankfurt as area medical advisors. And we took with us on this trip my grandfather’s written history of his war time experiences in a tank battalion – he came in on Omaha Beach on D+3 and fought all through Europe, including in the Bulge. He was an excellent writer and detailed in vivid clarity his wartime experiences. After the war my grandfather was a very complicated man and very difficult on my mother in particular. So much so that she really couldn’t have much of a relationship with him. He died a few years back, but as we were visiting those battlefields in Luxembourg and Belgium, my mother had the very sweet and loving assurance that her dad was grateful we were there, that he wanted her in particular to understand what had happened to him, and that he loved her more than he was ever able to express in life. We forgot, I think, that even those who survived those experiences left parts of them behind on those battlefields. I’m grateful to know that all those young boys will be restored fully and that the relationships and love they couldn’t experience in this life will be given to them freely in the next.

Jason

Jason, thanks for sharing your experiences in Normandy and other World War II sites in Europe, along with the information about your grandfather. His wartime journal must be a family treasure.

For those who have never experienced the horrors of combat, it’s sometimes hard to understand why veterans find it difficult to re-assimilate in society and sustain normal interpersonal relationships. And the other parties to those relationships often become collateral damage of a war fought decades before. It’s nice to know that your mother found some peace and comfort during her time with you a few years back in Luxembourg and Belgium.

Eric –

If you haven’t read it already, I highly recommend Rick Atkinson’s “The Gun’s at Last Light,” the third volume his Liberation Trilogy about the western theater in World War II. He does a superb job of portraying the logistics and individual bravery of those who fought on D-Day.

As for the attitude toward Americans among the French, I have to share a story. Toni and I first went to France in 1993, when our kids were 13 and 7 years old. It was our first time in Europe and we had no idea what the customs were there. We were driving from the Ardennes Forest in Belgium to Paris and trying to make good time. So we put off lunch until around 3 pm, when we passed through Sedan, a small town on the border of Belgium and France. We thought we’d just stop into a fast food restaurant, grab a quick hamburger, and be on our way.

We had no idea that every restaurant in town would be closed after the lunch hour and that the concept of a fast food restaurant at that time was pretty much unknown in small town France. Our kids were starving and cranky, nothing was open, we had no snacks in the car … we were out of options. We finally found an ice cream parlor that was open and went inside.

All they had was ice cream and our kids were not happy.

The owner’s English was truly terrible (but much better than our French), but somehow we managed to communicate that we were looking for some food that was not ice cream … AND … that we were from America.

That last bit of information did the trick. The owner said (in broken English), “Oh, you are Americans! My wife is from Normandy, so of course she loves Americans. Let me go get her.”

And he did. He closed his ice cream shop (leaving us inside), went home and got his wife, who came back to the shop, greeted us warmly, and cooked us a delicious real meal of crepes.

It’s one of the warmest memories I have of traveling in other countries.

Doug, I have read all three volumes of Atkinson’s Liberation Trilogy and thoroughly enjoyed each one—especially “The Guns at Last Light.” And I’m anxious to read the first volume of his history of the Revolutionary War. The man knows his stuff and knows how to write.

The story of your liberation from hostile children by the couple in Sedan is delightful. It was one thing for them to feed you—but crepes. C’est magnifique!

Eric, I’ve read Atkinson’s first volume of his Revolutionary War trilogy. You’re in for a treat. It’s every bit as good as his WWII trilogy.

As with several folks on here, we visited Normandy and the cemeteries several years ago. Definitely a moving experience, reading the inscriptions on the gravestones, and thinking about the incalculable losses of sons, fathers, and husbands, on both sides.

Reflecting on hard times like WWII and other challenging historical periods (Civil War, etc.) makes me quite optimistic actually. People moan about the current challenges and cleavages in society today, but we’ve seen worse and I think we’ll make it through fine. (And have more and different challenges to face!)

I share your perspective, Jeff. I’m pretty much a half-glass full kind of guy. Also, when it comes to fretting about the future of our country, I learned a very valuable lesson several years ago while watching Tom Hanks in the movie, “Bridge of Spies.” (Both the film and the book are quite good, by the way.)

In this film, which is based on a true story, Hanks plays the part of a lawyer (James B. Donavan) in the late 1950’s who is called upon to represent Rudolf Abel on charges of espionage, specifically, spying for the Russians. When Hanks met with his client for the first time, he explained the charges, noting a conviction could result in the death penalty.

When he finished, Hanks was a bit surprised by his client’s calm demeanor and seeming lack of concern, so he says, “Mr. Abel, aren’t you worried about what might happen to you if you are convicted?” Abel, with just a hint of a smile, responded with a question of his own: “Would it help?”

Eric as usual a great read. David and I just returned from Normandy, the museum, the cemetery and Omaha Beach. Its hard to even discuss it at this time. Something that weighs on my mind is something our tour guide told us about how Hitler was fooled into thinking the invasion was going to happen in a different place. Two resistance leaders were given false information, then “outed” to the Germans. Under torture they give up the false info. To be clear, these two thought they had good information. I feel sad for what they went through, but feel equally sorry for whoever had to make that decision.

Thanks, as always, Karen for taking the time to read my stuff.

The deception to which your tour guide was referring had a code name: Operation Fortitude. And it involved much, much more than giving false information to resistance leaders.

The Allies wanted Hitler to believe they would be landing in Northern France at Pas de Calais, directly across from Dover, which was the shortest distance between England and France. They constructed scores of wooden tanks and other equipment which they arrayed, under thin camouflage, in the fields around Dover. Then they summoned General Patton to Southeastern England to assume command of these phantom armored divisions.

Hitler bought it, but Germany’s greatest tank commander, Erwin Rommel, was convinced the Allies would land in Normandy. Rommel, however, couldn’t persuade Hitler he was right and was ordered to deploy his forces near Calais. By the time Hitler realized he was wrong, the Allies already had a secure beachhead and were beginning to advance East and South in France.

Hitler suffered from “Midas Syndrome.” His bold invasions of Czechoslovakia, Poland, and France, against the advice of his generals, convinced him that he was smarter than his advisers, that everything he touched would turn to gold. If Hitler had let his generals conduct the war—simply get out of the way—the whole affair might have turned out differently.