Human beings and virtually all animals possess exceptional navigation skills. Monarch butterflies, for example, fly south to Mexico for the winter and then return north in the spring, traversing some 2,500 miles. The travel time is so great it eclipses multiple lifespans. It is the great-grandchildren of these fragile, winged creatures who complete the journey. But how do the newborn know where they’re going? This is a mystery science has yet to unravel.[1]

Monarchs wintering in the Monarch Grove Sanctuary Preserve, California

Monarch Butterfly Waystation, Berwyn Heights, Maryland, by Geraldshields11

But no one can beat the Arctic tern, a four-ounce bird that travels nonstop each year from its nesting habitats in the northern regions of North America and Eurasia to Antarctica, a round trip of some 44,000 miles. The average tern lives thirty years, which means that it will make the equivalent of three trips to the moon and back during its lifetime.[2]

Humans are no less remarkable in their ability to navigate their surroundings; we are by nature explorers with an innate ability to use the landscape as our guide. The Inuit in the Arctic rely on astronomical observations and landmarks to find their way, even in seemingly featureless environments. For the uninitiated, all sea ice looks the same. But the Inuit are able to distinguish sea ice by color; they have over ninety different words to describe the various kinds. And where no visual cues are available, they rely on communal memory to recall the location of those routes that are visible only during certain periods.[3]

Single Outrigger Canoe (model), Woleai Atoll, by Yanajin33

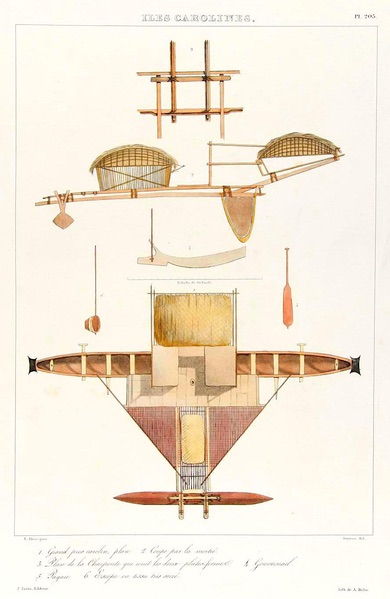

Lithograph of Caroline Islands Watercraft, by Admiral François-Edmond Pâris

Most impressive of all are the Caroline Islanders who navigate between islands in the South Pacific. They have the ability to read wave swells to determine the direction of their destination. This, combined with their excellent celestial navigation skills and their knowledge of reefs and animal behavior, allow them to reach their destination. The best navigators have committed to memory star maps for over 100 islands, spanning an area of thousands of miles.[4]

What is the mental process by which people and animals accomplish these extraordinary feats of navigation? Around 75 years ago, Edward Tolman, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkley, proposed that animals might have the ability to create a “cognitive map” of their environment, a hypothesis he developed while testing the behavior of rats in a maze.[5] His theory has since been validated—for both animals and humans.

In the words of science writer, M. R. O’Connor, navigation involves “not only literal travel through space but also mental travel through time….”[6] The latter occurs through the planning of the trip and the plotting of one’s course to a new destination, or via the recollection and visualization of a route previously traveled. By remembering the past, focusing on the present and imagining the future, we can pinpoint our destination.

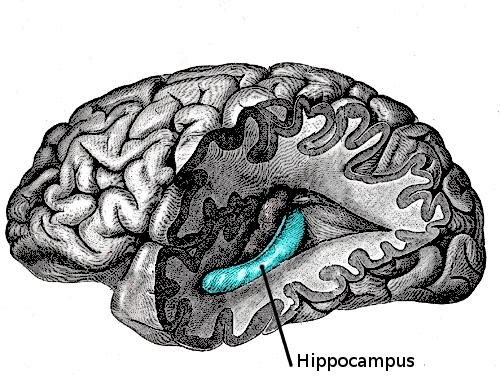

But where in the brain is this information collected and stored? Remarkably, in the same place for both humans and animals: the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure that resides deep within the temporal lobe.

This is not only where our mental maps are stored but also our memories. Further, our recollections seem to be inextricably linked to the place where we had our experiences.[7] “If we opened people up, we would find landscapes,” says the French director, Agnés Varda, in an autobiographical film about the places she loves.[8]

Interestingly, the hippocampus will grow or shrink, depending upon the frequency with which it is used. This was demonstrated in a well-known study of some extraordinary modern navigators: London cabdrivers. Before they can obtain an operating license, they first must master the layout of what is considered “the world’s most confusing city,” a process that usually takes two to four years. The scientists conducting this study discovered that experienced cabbies had far more gray matter in their hippocampus than the rookies.[9]

Over time, explorers have used a remarkable number of navigational devices—the compass, the sextant, the astrolabe, the clock, to name a few—to help them find their way. But the latest innovation—the Global Positioning System (GPS)—differs from its predecessors in one critical respect: it “replaces navigational demands with a very pure form of stimulus-response behavior (turn left, turn right).”[10] It lulls the user into passivity and switches off important mental processes, including the hippocampus.[11] As a result, we move through a world we do not see and have little or no recollection of the experience.

Worst of all is the strong correlation between a reduction in our gray matter and dementia. The presence of hippocampal atrophy is nearly universal in those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, a voracious form of dementia that annihilates the brain cells in the hippocampus.[12] And there is a domino effect: the diminishment of our spatial skills can impair our ability to recall the past, imagine the future and expand our understanding of the social world we inhabit.[13]

There are other disturbing developments in our society that have diminished our ability to ascertain our place in the world. The environmental psychologist, Harry Heft, believes there is a connection between his students’ unfamiliarity with history and their inability to get anywhere without their smartphones. History gives us a sense of where we are in time. Without a “strong background in history, I don’t understand how [my students] know their place in the world. GPS is a smaller example of that. I think my students are disoriented.”[14]

Michael Ravitch and Dianne Ravitch, the editors of a magnificent collection of English prose and poetry, voice similar concerns regarding the modern rejection of our literary tradition and disparagement of “dead white European authors,” such as Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Austen, Brontë and Keats:

Our ideas, our words, and our emotions do not belong to us alone; they bear the mark of those who have come before us. * * * But when we forget about them, we narrow our own horizons. Like it or not, we are their students; they are our models. We can despise them or disagree with them, but we cannot escape their influence. We only make ourselves irrelevant when we sever our links with our literary heritage.

Michael Ravitch & Diane Ravitch, Editors, The English Reader: What every Literate Person Needs to Know, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. xix

While the benefits of GPS are undeniable—a reduction in shipwrecks on the high seas, lives saved via remote pacemaker monitoring, and greater economic productivity—the concerns expressed by scientists, authors and educators about GPS-equipped smartphones cannot be easily dismissed. Do we lose something “when we cease being able to be lost?”[15] O’Connor articulates the dilemma eloquently:

None of us is exempt from the ramifications of the device paradigm. We all seem to find it extraordinarily difficult to step outside the onslaught, to create the distance and perspective between us and our devices that might allow us to question what cultural or cognitive price is being paid in return for convenience.

Wayfinding, p. 283.

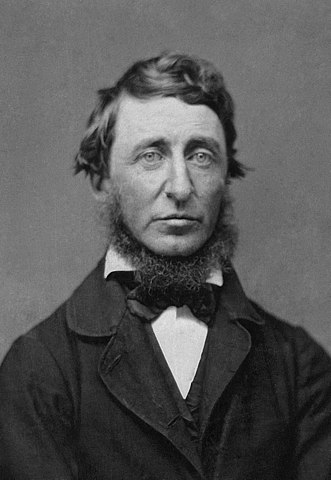

Henry David Thoreau, a transcendentalist and lover of paradox, presciently invites us to consider the benefits of losing our way: “It is a surprising and memorable, as well as a valuable experience to be lost in the woods at any time. * * * Not till we are lost, in other words, not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.”[16] Thoreau’s words echo a challenge directed by Christ toward his disciples immediately following Peter’s confession:

24If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. 25For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it. 26For what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul?

Matthew 16:24-26 (ESV)

In the original Greek, the word for “life” in v. 25 (ψυχὴν) is the same as “the soul” in v. 26. It can also mean “spirit.” In the world of the New Testament, man consists of “body, soul and spirit,”[17] the soul being the bridge between the other two. Hence, the paradox: we are given the option of saving our soul in relation to the body, but at the expense of losing it in relation to the higher life of the spirit.[18] But if we make the correct choice, we can have both.

If we opt to accept the Lord’s invitation to “come after him,” where will he take us? His earthly ministry provides the answer: to those in need. “But can you be more precise? Where exactly are these people? And how long will this take? Will the people I help appreciate my sacrifice, and what if they’re not willing to do their part? I gotta tell you, I’m feeling a bit disoriented here.” Any parish priest, Jewish rabbi, or Mormon bishop or Relief Society President can tell you how this feels.

A dear friend of mine, who was recently told by his doctor that his remaining days are now measured in weeks, has lived such a life of service. As a serious student of the scriptures, he willingly picked up the gauntlet Christ threw before him. By studying history, he learned the importance of courage, humility and compassion from people such as Major Joshua Chamberlain, General George C. Marshall, and President Nelson Mandela. This, in turn, inspired his love for the history of his family and the families of others.

Literature taught him the complexity of the human condition, along with the importance of listening to others and resisting the temptation to act impulsively. With this knowledge—which has been acquired in equal measure by his devoted wife—the two of them have found endless joy in being lost in the service of others.

Dick, I have no idea whether the realm to which you are about to travel will be better than the one you are leaving behind. But there is one thing of which I am certain: our world will be diminished by your absence. Godspeed, my friend.

[1] David Barrie, Supernavigators: Exploring the Wonders of How Animas Find Their Way, (New York: The Experiment, 2019) pp. 129-136.

[2] Jennifer Ackerman, The Genius of Birds, (New York: Penguin Press, 2016), pp. 199. Because the terns do not fly in a straight line, the distance they travel each year is considerably greater than 18,600 miles—a straight-line round-trip between the Arctic and Antarctic Circles.

[3] M. R. O’Connor, Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the World, (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2019), pp. 43-45.

[4] Ibid, pp. 236-243.

[5] Genius, pp. 209-210.

[6] Wayfinding, p. 7.

[7] Genius, p. 217.

[8] Robert Macfarlane, “The Landscapes Inside Us,” New York Review of Books, vol. LXVIII, no. 11 (July 1, 2021), p. 25.

[9] Genius, p. 219.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Wayfinding, p. 271.

[12] Ibid, p. 266.

[13] Genius, p. 219.

[14] Wayfinding, p. 19.

[15] “Landscapes,” p. 26.

[16] Henry David Thoreau, Walden; or, Life in the Woods, (New York: Library of America, 1985), p. 459.

[17] 1 Thessalonians 5:23.

[18] Charles John Ellicott, D.D. (Ed.), A New Testament Commentary for English Readers Vol. I, Second Edition(London: Bibliotheca Bodleiana, 1870), p. 102.

Lovely, thoughtful and touching. What a lot to ponder. Thank you deeply for sharing your love, intelligence, analysis, and ability to inspire us all.

Thank you for your kind comments and the honor of your dedication. You have been a true friend.

I love this post and the dedication to one of the mainstays of the Church community in Arlington regardless of which ward we attend.

I don’t think any of us knows how much Dick Hanneman has contributed to the happiness and goodness of others in his remarkable lifetime of service to his fellow man. He and Karen are an inspiration to us all and Dick will leave a big hole in our lives and hearts. God speed until we meet again!

Ahhh, Dick, thanks for being a spiritual constant in my life for so many years. Jill

Thank you, Eric, for your excellent essay! As always, well written. Well said! And, thank you Dick Hanneman! The Hymn “Each Life That Touches Ours for Good” reflects my sentiments for your life having touched me for good so many years ago.

Karen & Dick,

I must tell you that when I commenced this essay, I intended for it to go in a completely different direction. But it wouldn’t go there. It wasn’t until I was about two-thirds finished that the idea for the current ending—Thoreau, Christ, and you—came to mind. Call it inspiration, an epiphany or whatever. I’m just glad my usual stubbornness didn’t prevail.

I am starting medical school tomorrow and am very comforted by this post. Scott and I are no longer in Arlington, but always enjoy reading. Thanks for writing!

Thanks for taking the time to read my musings, Keena. I suspect that once tomorrow arrives your “leisure reading time” will be markedly curtailed. Best of luck with medical school!

Thanks Eric. As usual, you’ve given us much to ponder. I love reading your musings.

Great to hear from you, Rob. Hope Christine and you are doing well. And thanks for taking time to read my stuff and share your thoughts.