In 1783, Benjamin Franklin wrote an essay called, “Remarks Concerning the Savages of North-America,”[1] in which he chronicles an exchange of views about religion between a Swedish minister and the chiefs of the Susquehanna Indians. The man of the cloth began the conversation by reciting the biblical creation story and the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden. When he was done, a spokesman for the tribes stood and thanked him, and then proceeded to share his tribe’s origin story.

“In the Beginning our Fathers had only Flesh of Animals to subsist on,” he said, but relying on a single source for food was precarious for the tribe. One day, two young hunters, having slain a deer, were roasting the meat over an open fire in the woods. Just as they were about to begin their repast, a beautiful woman descended from the clouds and sat upon a nearby hill. This spirit, the warriors concluded, must have smelled the venison, so they offered her some.

She was delighted with the taste and decided to repay their kindness. “Come to this Place after thirteen Moons, and you shall find something that will be of great Benefit in nourishing you and Children….” They did as they were instructed and, much to their delight, they found maize growing where her right hand touched the ground and kidney beans where her left hand had rested.

The missionary was quite disturbed by their story. “What I delivered to you were Sacred Truths,” he declared, “but what you tell me is mere Fable, Fiction & Falsehood.” The tribal leaders were deeply offended, and suggested that there was a glaring gap in their accuser’s education: he had failed to learn the Rules of Civility. “You saw that we who understand and practice the Rules, believed all your Stories; why do you refuse to believe ours?”

I had a similar experience about 15 years ago while leading an Elders’ quorum discussion on the first chapters of Genesis. Because of my experience representing the Iroquois Indian nations in Upstate New York, I had become acquainted with their creation story and found it intriguing; so I decided to share it with the class.

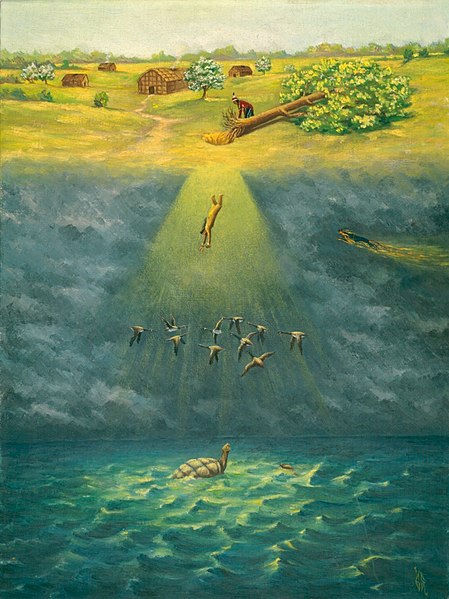

In the beginning, men and women lived on an island floating in the sky at the center of which was a large tree. One woman, much to her amazement, discovered she was pregnant. When she told her husband, he was so angry that he tore the tree from its roots, creating a gaping hole in the center of the sky island through which he pushed his wife.

The earth towards which she plunged was covered only with water, so it appeared she would drown or be killed on impact. But just before she hit the surface, two birds caught her on their backs and brought her to the water animals, who resolved to help her. Following the lead of the frogs, they gathered mud in their mouths from the bottom of the sea and spread it on the back of a large turtle, creating what came to be known as “Turtle Island,” the Haudenosaunee word for North America.

“Sky Woman,” as she came to be known, brought with her plants—strawberries for food and tobacco for medicine—which sustained her. She then gave birth to two sons. One created all the good in the world while the other fathered the evil. Eventually they fought and the righteous son prevailed.[2]

When I finished, one member of the quorum said, “The thing that distinguishes our creation account from that of the Indians is, ours is true.” While this brother’s view (and that of Ben Franklin’s Swedish minister) is shared by most Latter-day Saints[3] and other fundamentalist Christians, most biblical scholars—both Mormon and non-Mormon—believe it is wrong. Their view (and mine) is that both stories are true in the sense that each contains important spiritual truths and both are false in a historical sense. But neither was ever intended by its authors to be a literal account of earth’s creation. Rather, they are myths.

In modern society, the word “myth” has a pejorative connotation. Myths are dismissed as a primitive way of understanding the world. Since they are neither historically nor scientifically accurate, they must be false. But myths are an essential element of all cultures. They are metaphorical stories that transcend the limits of nonfigurative language. Myths strive not for historical accuracy; instead, they are often metaphysical, teaching something of collective importance to the author’s community.[4]

The creation story in Genesis has nothing to do with science or history; rather, it is a profound mythical and theological meditation about the God of Israel and “Israel’s place in the world as God’s people.”[5] And to understand it, we must acquaint ourselves with the historical context in which it was written.

Most scholars agree that the Pentateuch—the first five books of the Old Testament—were not composed until the 6th century B.C. during the most traumatic episode in Israel’s history: the conquest of Palestine by Nebuchadnezzar, the destruction of the Temple, and 50 years of captivity in Babylon.[6]

The loss of their homeland was a national catastrophe, one that raised existential questions about the future of the Israelites and their relationship to God. They sought to answer those questions by retelling—and editing and compiling—their oral traditions and records to produce what we call the Old Testament. Thus, the People of the Promised Land became the People of the Book.

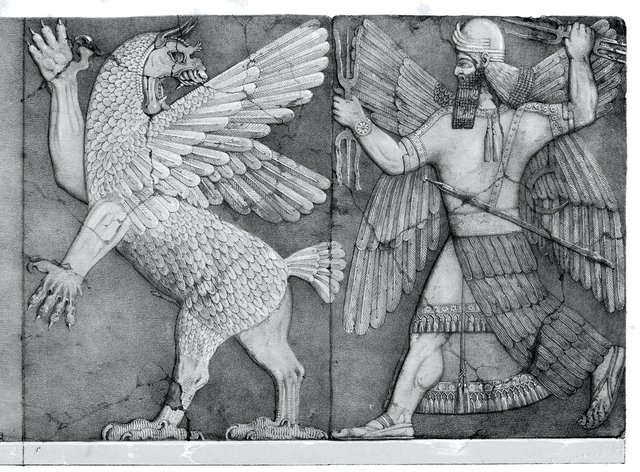

The Genesis creation story contains elements from several ancient myths, especially Enuma Eliš, the Babylonian Creation Account. The similarities between the two tales are striking. They “breathe the same air,” in the words of one scholar.[7] But so are the differences. Indeed, Genesis is rightly seen as a rebuttal to the Babylonians’ origin story.

Enuma Eliš explains how Marduk became the chief deity in the Babylonian pantheon of Gods. He did this by defeating all contenders for the throne. Once he had established order in the universe and assigned roles to the lesser gods, he proceeded to create earth and man. The Genesis account, by contrast, is monotheistic, at least in the sense that there is only one god of this world.

The Israelites’ view of mankind is also radically different from what is described in Enuma Eliš and other ancient creation accounts. Their origin story is the only one where humans are created in God’s image. In other words, we are like God and, in a sense, we represent him. Also, Israel’s God, unlike Marduk, personalizes his human creations: he gives them names and regards them as his offspring. In polytheistic societies mankind merely exists to perform the labors of the gods while our Father in Heaven seeks glory through the eternal progression of his sons and daughters. Jehovah weeps when we stray from the path of righteousness. Marduk doesn’t give a damn.[8]

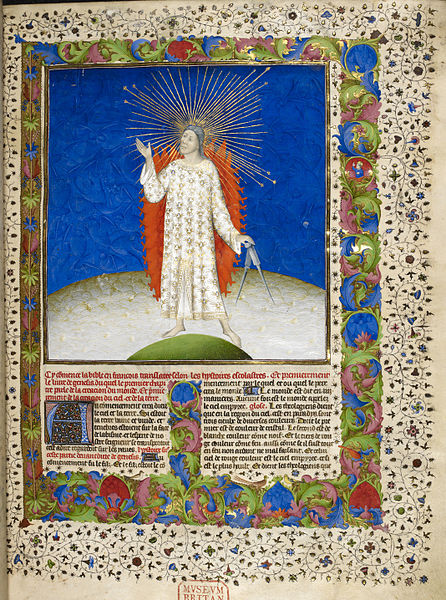

The first chapter of Genesis also is different from its ancient counterparts in that it occurs over seven days. This is a careful literary arrangement, and the days in question are 24-hour periods, not “eras” or “long periods of time.”[9] Rather, this calendrical device is used to parallel the account of the construction of the tabernacle in Exodus.[10]

In addition, it was inspired by Near Eastern and Israelite ideas of temple construction and consecration, which occur in time periods divisible by 7. For example, Solomon took seven years to build the Temple and its dedication ceremony lasted seven days, which was followed by a seven-day feast.[11] All ancient readers would have understood that the seventh day was the climax of the Genesis creation account, for Deity rests in a temple and only a temple. In other words, Earth is God’s cosmic temple.[12]

While the Israelites sacred space in Jerusalem had been destroyed, they still had sacred time—the Sabbath[13]—to sustain them in Babylon, and then later when the Romans destroyed Herod’s temple. This burning desire to retain some connection with the Promised Land and the Temple had a profound influence on the way they redacted and presented their origin story.

The culture of the Israelites, especially their patriarchal society, also informs their creation narrative. God deals principally with Adam in the Garden while Eve is placed in a subservient position. By contrast, the female spirits and protagonists in the Native American creation myths suggest a matriarchal society. Indeed, tribal membership among the Iroquois nations continues to be determined with reference to the lineage of the mother. And while the governing bodies of traditional Iroquois governments are comprised exclusively of men, they are appointed by their clan mothers, who are also charged with preserving the tribe’s history.

Also, nature is at the heart of their origin stories. The animal and plant kingdoms are merged in the creation of “Turtle Island.” To the native peoples, the most striking elements of our creation myth are the naming by Adam of the animals and God’s directive to “till and keep the Garden,” passages to which we typically ascribe little significance. But by having Adam name the animals, God personalizes them and imbues them with a spirit that demands our reverence and respect. Indeed, the Creator’s spirit fills all of Nature. In a very real sense, the indigenous peoples regard all of Turtle Island as God’s temple.

The Israelite and Native American creation myths, when read in context, beautifully illustrate how the Lord, when revealing gospel truths, speaks to different peoples in their language and at their level of understanding.[14] While those stories employ noticeably different metaphors and figurative language, their message is the same: Earth is sacred space. This willingness to engage with us in our imperfect mortal state is the condescension of God. And without God’s condescension, our knowledge of God would come to an end.[15]

We turn our backs on this most precious gift when we try to harmonize ancient scriptures with our contemporary culture and modern science. There is not a single instance in the Old Testament where Jehovah attempts to convey “scientific information that transcended the understanding of the Israelites.”[16] The cosmology of Genesis was the cosmology of the ancient world. It served as a structure—a nonscientific and ahistorical structure—on which Jehovah could craft an origin story to teach the Israelites the purpose of his creation: “to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man.”

[1] Benjamin Franklin, Writings, (New York: Library of America, 1987), pp. 969-974.

[2] There are many different versions of this legend. See Anthony Wonderley, Oneida Iroquois Folklore, Myth, and History,(Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2004), pp. 57-86.

[3] Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Dana M. Pike, and David Rolph Seely, Jehovah and the World of the Old Testament, (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Company, 2009), p. 25.

[4] Marc Zvi Brettler, How to Read the Bible, (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Jewish Publication Society, 2005), pp. 38-39.

[5] Peter Enns, The Evolution of Adam, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: BrazosPress, 2012), p. 56.

[6] See, e.g., Peter Enns and Jared Byas, Genesis for Normal People, (Englewood, Colorado: Patheos Press, 2012), pp. 7-9.

[7] Peter Enns, “Genesis 1 and a Babylonian Creation Story,” (BioLogos, 2019).

[8] Christine Hayes, Introduction to the Bible, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2012), pp. 29-42. See alsoJohn H. Walton, Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2006).

[9] John H. Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate, (Downers Grove, Illinois: Inter-Varsity Press, 2009), p. 90. There are occasions where the Hebrew word for “day” (yôm) is used in the scriptures to refer to an indefinite period of time, but there the word is being used idiomatically: “In that day,” which is simply a Hebrew way of saying “when.” This is clearly not the case in Genesis.

[10] Ben Spackman, “Priests, Babylonians, and Seven 24-hour Days of Creation,” May 4, 2020.

[11] The Lost World, pp. 87-89.

[12] The Lost World, pp. 71-76.

[13] John H. Walton, Victor H. Matthews, Mark W. Chavalas, The IVP Background Commentary: Old Testament, (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 2000), p. 513.

[14] D&C 1:24.

[15] The Evolution of Adam, p. 58.

[16] The Lost World, pp. 17, 105.

I was in a traveling chamber choir as a young adult and we sang a dozens of churches in the area. It was really eye opening to see that their faith was formed in the same way and just as deep and rich as my own. Even more so, that I felt “the Spirit” so strongly in their midst. This post really resonates with where my faith is today.

I have had the same experience, Stephanie, when I’ve visited other churches. I especially love being exposed to their sacred music, which is often greatly enhanced because the acoustics in their houses of worship are generally superior to ours.

As I’ve said before, the work of the restoration is too vast and difficult for any one faith tradition to handle on its own. We are just one group among many who are furthering that effort.

Really interesting history and context, thanks for all of your research, impressive.

You’re quite welcome, Jeff. I’m glad you enjoyed it. And thank you for taking the time to read it.