Christmas stimulates our senses like no other holiday. The dazzling holiday lights and decorations, the scent of pine from the tree and the aroma of roasted chestnuts emanating from the street vendor’s cart in the big city, that first sip of cinnamon-laced eggnog (we’ll pass on the fruitcake, thank you very much), the heft and feel of an unwrapped present, and the warm embrace of friends and family with whom we reunite. And my favorite of all: the laughter of children and the music of the season. Especially the music.

The sensory appeal of the holiday is not surprising since Christianity is very much a materialist religion, emphasizing the physical world and the human body as vehicles of the divine. In Medieval Europe this belief often found expression in an intense desire to be near the relics of the saints and martyrs, sacred objects that were frequently venerated in magnificent religious structures. The Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, for example, was built in the 1240s by Saint Louis to house the Crown of Thorns, believed to have been on Christ’s head during the crucifixion.[1]

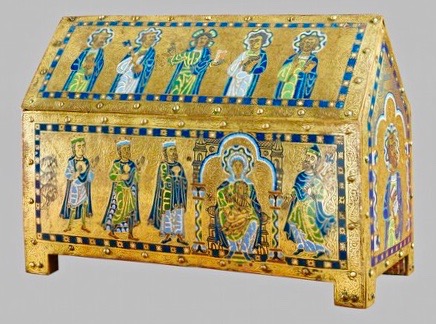

Within cathedrals, churches, and royal palaces, holy relics were typically stored in beautiful chests and altars—reliquaries—that were often great works of art. The workshop of the Abbey of Saint-Martail in Limoges in South Central France produced several such artistic treasures, including the stunning Magi Reliquary made around 1175-80 that now resides in Washington’s National Gallery of Art.

The primary panel of this reliquary depicts three kings bearing gifts as they approach the Christ Child and his mother, Mary. But she is not shown in a humble manger but on a magnificent throne, and by her side is Joseph, who holds a royal staff, adorned with a lily, a Christian symbol of Mary’s virginity. The sloped rooftop of the box—ostensibly intended to resemble a house—shows the Savior with Peter on one side, holding his key to the kingdom, and John the beloved on the other. They are joined by two unknown saints.[2]

The legend of the Magi is part of Matthew’s infancy narrative. Along with the first two chapters of Luke, this story is an example of a creative genre of Jewish theological writing known as Haggadah (meaning “narrative”). As the biblical scholar, Jeffrey John, explains, a haggadoth “starts from a scriptural text but then weaves upon it very freely, using threads of prophecy-fulfillment, symbolism, typology, allegory or numerology to create a new story that reapplies the truths, hopes, patterns and meanings of the scriptural past to the present.”[3] Most biblical scholars believe that the birth stories of Matthew and Luke consist primarily of Old Testament themes and references reimagined to illuminate the meaning of Christ’s birth.[4]

As to the three kings, they are a typological reference to the story of Balaam, an occult visionary who had been dispatched by the King of Moab to cast a curse on Moses, but who, upon encountering the Israelites, had the following vision of the future: “There shall come a man out of Israel’s seed, and he shall rule many nations. I see him, but not now; I behold him, but not close: a star shall rise from Jacob, and a man [scepter] shall come forth from Israel.”[5]

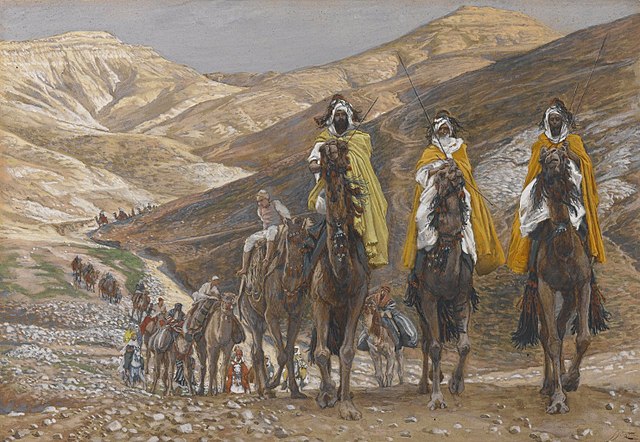

Matthew also employs the legend of the Magi to illustrate the destiny of Christ’s gospel, an outcome he knew firsthand since he composed his gospel several decades after the resurrection. It begins by showing the manner in which the news of salvation draws believers—the three kings—who significantly are Gentiles.

The Gentiles, deprived of the scriptures, had never received the explicit revelation as to the nature and mission of the Messiah that was given to the Israelites. So God reveals himself to them through nature. Thus, it is through astrology—the birth star of the King of the Jews—that Matthew shows the good news of salvation to the Gentiles. But Christ’s identity is not fully understood by them until they are taught by the Jews the history of salvation.[6]

The evangelist continues his story by creating a paradox. The wicked King Herod, troubled by the birth of a potential usurper, inquires of the chief priests and scribes as to where the Messiah should be born. They, in turn, consult the scriptures, and reply: “Bethlehem of Judea.” (Matthew 2:4-6.) Herod and his co-conspirators then plot to kill the baby Jesus, prompting his parents to flee with their child to Egypt. Thus, those that had the scriptures and the plain teachings of the prophets refused to worship the newborn king while the Gentiles, without the benefit of sacred texts and prophecies, readily embraced him.

The beautiful Magi Reliquary produced in Medieval France discussed at the beginning of this essay is also imbued with its own ironies. This was a box intended to house the relics of the three kings—men who opened their own boxes of treasure for the Christ Child. But they, in return, received from their Savior a gift of inestimable value: eternal life.

[1] MacGregor, Neil, Living with the Gods, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018), pp. 206-207.

[2] E. A. Carmean, Jr., “A Reliquary Fit for a King—or Three,” The Wall Street Journal, January 5, 2019.

[3] Jeffrey John, The Meaning in the Miracles, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2004), p. 8.

[4] Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, (New York: Doubleday, 1993), pp. 32-37.

[5] Numbers 24: 7, 17—partially the Brenton Septuagint translation. Quoted from Raymond E. Brown, An Adult Christ at Christmas, (Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1988), p. 12.

[6] Raymond E. Brown, An Adult Christ at Christmas, (Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1988), p. 13.