Author’s Note: This essay was first published in October, 2020. I have since revised it, adding some additional observations about the Abrahamic Covenant and what it means to “honor our father and mother.” I have, of course, retained the touching story at the end about one man’s (and one nation’s) eternal debt to his mother. I have chosen to republish it today as we commence our annual tribute to the matriarchs in our lives.

When my parents married, my mother was not a member of the church and my father, who hailed from a long line of Latter-day Saints, had been inactive for some time. But each of them had strong religious convictions and desired to find a place to worship where they would feel comfortable.

When I, their firstborn, arrived they were attending the Presbyterian Church in my hometown, Champaign-Urbana, Illinois. So, I was baptized and added to the church register shortly after my birth. But a couple of years later my parents decided to join the local Methodist congregation in Danville where I underwent the rites of baptism a second time.

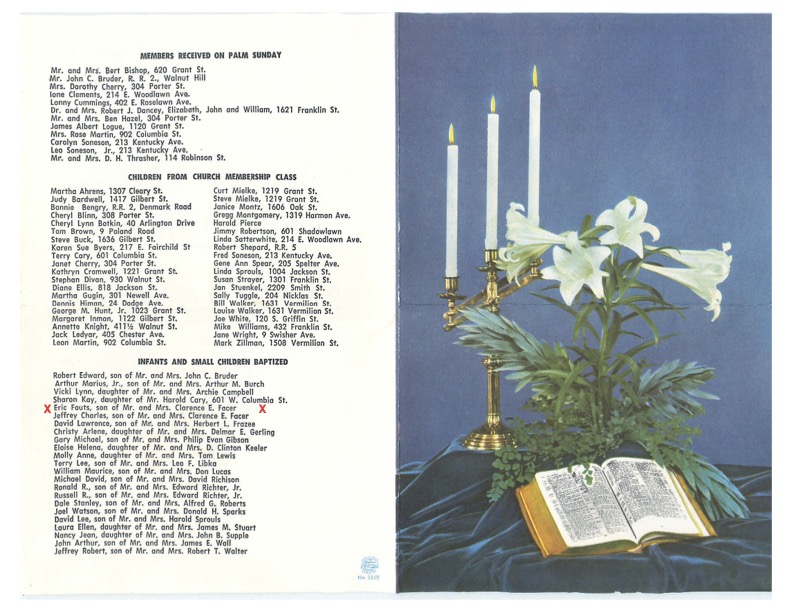

Bulletin for the week of April 10, 1955 (red “X’s” announce my baptism).

After the passage of a few more years, my father’s roots pulled him back to the faith of his fathers—Mormonism—where I completed the hat trick by entering the waters of baptism a third time. My mother followed suit a few years later and we all stayed put.

I have never regretted my parents’ spiritual wanderings when I was a child. I especially enjoyed our brief sojourn with the Methodists since they had a nifty playground you could use, even on Sundays. I can see why Joseph Smith thought highly of them. And, as a lawyer, I have learned the value of covering your bases, working both sides of the street, so to speak.

While sorting through my mother’s papers several years ago shortly after her passing, I came across a letter addressed to me from the reverend of the first church we joined. I was taken aback by this discovery, especially when I noticed that it was written less than two months after I was born. Here are some of things this Presbyterian minister had to say:

Dear Eric:

I know you will tell me you cannot read; that it is a joke. With a mother and father like you have, you will be reading this without any trouble.

Your mother is a very fine lady, none better. She will give to you all the needs and joys which a mother can give. Now go easy on the crying when your mother has other things to do. There is a time to cry and I will tell you when that is. Be very kind to your mother, she works hard for you.

Now maybe you think you need attention; you cry when your daddy is home so that he can give you that attention. When he sits down to read the paper, that is the time to cry, and I’ll bet he will pick you up. Try it. There are many things your daddy will do for you, like play ball, push you in the buggy, walk with you at three in the morning, or just any time at night. Love your daddy; he will be a pal of yours for life.

I am certainly glad you are around, and I hope for you all the blessings which God can give to you and that you grow in “Wisdom and favor with God and man.”

Excerpts from the letter of Reverend Roy B. Connor, Jr., Minister, to Eric Facer, September 3, 1953

The prophecies of this thoughtful servant of the Lord were fulfilled to the letter and then some (except, perhaps the part about me growing in wisdom). My parents, though not perfect, cared and sacrificed for me, taught me the difference between right and wrong, and loved me unconditionally. It’s hard to ask for more than that.

Since the passing of my mom and dad, I often find myself reflecting upon the fifth of the Ten Commandments: “Honour thy father and thy mother: that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee.”[1] While studying the contextual origins of this admonition, I discovered there are many things about the Ten Commandments in general and the Fifth Commandment in particular, we misconstrue or simply do not comprehend. This is because we read them through modern, western eyes, and not as they would have been understood in ancient times.

While the Ten Commandments articulate the demands of the Abrahamic Covenant,[2] the Israelites’ understanding of their covenant relationship with Jehovah was more nuanced than our own.

The word covenant in Hebrew (berit), had different connotations depending on the relationship and relative standing of the parties. On the one hand, it was frequently used in a contractual sense, such as inter-family marriage agreements and debt servitude arrangements, each of which was enforceable.[3]

But it also referred to agreements—what today we call “treaties”—between kings who desired to create alliances and preserve the peace. When the two parties were of comparable size and strength, they were called “parity treaties,” with the sovereigns referring to each other as brothers.[4]

If, however, one party was superior to another, the arrangement was called a “suzerainty treaty,” i.e., a mutual understanding between the suzerain and his vassal.[5] In this dynamic, the overlord exercised some control over its subject while his vassal retained its autonomy within its realm. The Israelites appropriated this metaphor to describe their relationship with Jehovah. Thus, God was the father, the husband, the owner, or the master of Israel.[6]

The existence of two tablets on which the commandments were inscribed provides further support for the notion that the Decalogue was modeled after ancient contracts and treaties. Each party to such an arrangement would have been given a copy of the agreement/tablet. Likewise, ancient treaties often stipulated that they were to be read aloud publicly from time to time.[7] So, too, with the Decalogue.[8]

Given the outsized power of the father and the tendency of the Israelites (and the rest of mankind) to stray, the continuity of the relationship depended exclusively on the celestial patriarch’s mercy and his belief that his children, if forgiven, would be more diligent in keeping his commandments in the future.

Contrary to popular belief, the Ten Commandments were not laws; they were instructions. No penalties or curses were threatened if they were ignored. Further, they were given to the Israelites and to no one else. While they find expression in many of the parables and sermons delivered by the Savior during his earthly ministry and are a part of the moral code of many faith traditions, they speak to the specific needs and challenges confronting the Israelites.

Moreover, they were given to adults, not children.[9] Thus, the Fifth Commandment was not targeted at rebellious teenagers or children who refuse to eat their vegetables or do their chores. Rather, it speaks to the importance of adult children respecting and caring for their aging parents in a society where there were no nursing homes, Social Security or Medicare.[10]

This commandment underscores the centrality in ancient Israel of both the nuclear and extended family, one presided over by a patriarch. Further, the positioning of the Fifth Commandment—coming on the heals of four stern admonitions regarding the Israelites’ obligations to God—suggests that few things are more important than honoring our earthly patriarchs. In ancient households, failure to respect your father was tantamount to rejecting God.

The dominant patriarchal motif of the Decalogue, however, is softened in the Fifth Commandment, which specifically references the mother.[11] Given her indispensability in both the family and the community, she is to be honored and respected by her children in equal measure.

This commandment is also unique in another respect. It is stated in positive terms—no “thou shalt not” here—and it promises a reward: “that thy days may be long in the land.” Ancient Near Eastern legal documents make the right of children to inherit their parents’ property contingent on honoring them by providing and caring for them.[12] Here, God applies this condition on a national scale: The right of future generations of Israelites to inherit the Promised Land from their parents is contingent upon honoring them.[13] The significance of this assurance cannot be overstated. Possession of the land consecrated for their benefit was everything to the Israelites.

Lastly, in ancient Israel, the obligation to honor and respect one’s parents did not end upon their death. It also entailed performing appropriate burial rituals and caring for the family tomb in order to improve the condition of happiness of the deceased in the afterlife.[14]

There is also evidence that the Israelites engaged in the practice of feeding the dead—for example, placing loaves of bread on a grave—to make their existence in Sheol, the underworld in Israelite theology, more comfortable.[15] This should resonate with Latter-day Saints since we have a similar custom: we honor and respect our deceased parents by performing temple rituals on their behalf, thereby comforting them spiritually.

I believe, however, the principal beneficiaries of our temple rituals are not the dead, but the living. For they serve to remind us that we all stand on the shoulders of giants, be they our parents or others who have helped us along our way. This is true of both the weak and the powerful among us, as illustrated by this touching story.

Saying Goodbye

Two hundred years ago, the mother of an impoverished nine-year old boy and his older sister living in a small Indiana community unexpectedly died. A year later, his father remarried and his new wife brought three children of her own to the family.

The stepmother was shocked by the emaciated and scantily clad condition of the children, whose stomachs had grown “leathery” from going so long without food. She fed and clothed them, and loved them as if they were her own.

Another contribution she made to her new family was a small collection of books, which seemed odd since she could barely read. But the boy quickly devoured them, astonishing her with his ability to memorize long passages.

When he was 22, her stepson left home to find his own way in the world. He performed manual labor for a time, and then attempted to run a small store, which failed. He also tried his hand as a blacksmith and a surveyor, before deciding to study law, an area in which he truly excelled.

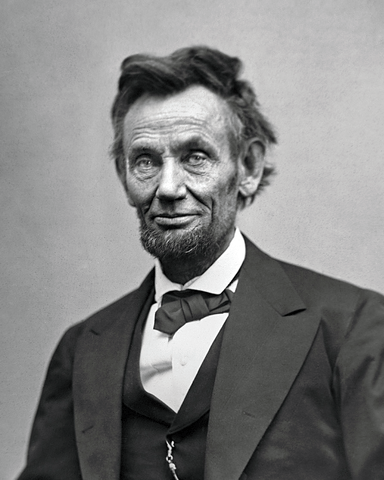

Around 30 years later, however, he gave up his legal career to pursue a new opportunity back east. Before embarking on this adventure, however, he traveled 120 miles on a freight train to say goodbye to his stepmother, who, twice widowed, was now living in a small farmhouse in Charleston, Illinois.

The two reminisced about his childhood, he praising her for having made him and his older sister “more human.” She later noted that, “his mind and mine, what little I had, seemed to run together, more in the same channel.” Their fondness for each other was palpable.

She embraced him when they departed and, like all good mothers, expressed abiding concern for his safety and welfare. But her fears were greater than most since she believed there were men in the world that wished to do him harm. He tried to reassure her, saying, “Mama (he always called her by that name) they will not do that. Trust in the Lord and all will be well. We will see each other again.”[16]

When her time came in 1869, Sarah Bush Johnson Lincoln was buried in the black dress given to her that day by her stepson, Abraham Lincoln, who had predeceased her by four years. Her fears, as it turns out, were prescient. It was as if, when they parted, each was already grieving the loss of the other.

Before making the arduous 2,000-mile trip to Washington to become the 16th President of the United States, Lincoln paid homage to the woman who arguably made it all possible. He knew the debt he owed her was one he could never repay.

It is this attribute that our earthly parents have in common with our heavenly ones: each has given us life and the love needed to make it worth living, something we are incapable of ever fully reciprocating. For this reason, the only individuals we are commanded to honor in this life are our Heavenly Father and Mother and our earthly parents. The First and the Fifth Commandments form a bridge between the celestial and the terrestrial, reminding us of our duties to God and of our obligations to our mortal mothers and fathers.

[1] Exodus 20:12 (KJV).

[2] Michael Coogan, The Ten Commandments: A Short History of an Ancient Text, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2014), p. 23.

[3] Ibid, p. 13.

[4] 1 Kings 9:13; Amos 1:9.

[5] Coogan, p. 14.

[6] 2 Kings 16:7.

[7] Coogan, p. 18.

[8] Deuteronomy 31:10-12 (The divinely written law was to be read ‘every seven years …at the festival of booths…before all Israel…men, women, and children.”)

[9] See Barton, John and John Muddiman, Editors. The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 81.

[10] John H. Walton, ed, Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary, Vol. 1, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 209), p. 233.

[11] Coogan, p. 78.

[12] Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds., The Jewish Study Bible (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, New York: 2014), p. 142.

[13] John H. Walton and Craig S. Keener, NKJV Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible, (Grand Rapids Mission: Zondervan, 2017), p. 151

[14] Herbert Chanan Brichto, “Kin, Cult, Land and Afterlife—A Biblical Complex,” Hebrew Union College Annual, Vol. 44 (1973), pp. 1-54.

[15] Deuteronomy 26:14; Tobit 4:17; Coogan, p. 79.

[16] Ted Widmer, Lincoln on the Verge, (New York, New York, Simon & Schuster: New York, (2020), pp. 76-77.