Sacrifice

As a passionate student of the American Civil War, I have visited many battlefields and other historical sites where the Bellum unfolded. But still on my list—until the fall of last year—was Charleston, South Carolina, the location of Fort Sumter, where the War Between the States formally began on April 12, 1861. I went there primarily to pay homage to Major Robert Anderson, the commander of the U.S. forces stationed in Charleston and perhaps one of the most important unsung heroes of our country’s fight for survival.

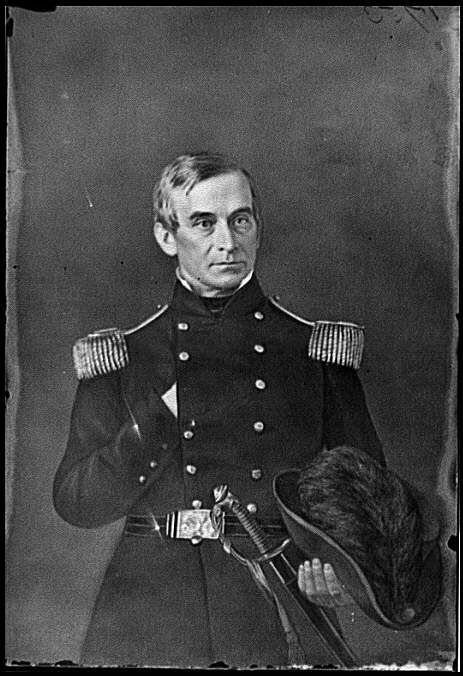

Major Anderson was ordered to assume command of two companies of Federal soldiers stationed in and around Charleston in November 1860, shortly after Lincoln was elected President. Tensions were high and talk of secession was rampant, creating a hostile environment for anyone sporting the uniform of a U.S. Army soldier.

Shortly after South Carolina seceded from the Union on December 20, Anderson, in the dead of night, secretly moved his small garrison from Fort Moultrie, which was located on an indefensible peninsula, to Fort Sumter in the center of Charleston Harbor. His actions triggered an outcry in the city, positioning him and his soldiers on the receiving end of numerous accusations and threats.

Robert Anderson was 55 when he was assigned to Charleston, where he found himself in an inordinately stressful situation. Born in Kentucky and himself a former slaveholder, he was sympathetic to the views of the South. But his loyalty to the United States, to which he had sworn an oath, never faltered.

His job was rendered all the more difficult by the paucity of guidance and direction he received from Washington. How was he to respond to acts of provocation, which at times threatened the lives of the men under his command? Were reinforcements on the way? And when would they be resupplied with desperately needed food stores, clothing, and military equipment? More often than not, the response he received to these questions was only crickets. So, he was left to his own devices.

There were many occasions when Anderson would have been justified in responding with force to the hostile acts of the South Carolina militias. But as a veteran of the Mexican-American War, he had witnessed firsthand the human suffering and loss attendant to armed conflict and knew that it exacted a fierce toll on both the victorious and the conquered. Thus, he opted for restraint.

Little did he know that his slowness to anger likely altered the direction—and maybe even the outcome—of the coming conflagration. For if he had answered in kind to the provocations of his adversaries—a course of action his junior officers often encouraged—his actions might have been perceived as hostile by the border states (Kentucky, Delaware, Maryland and Missouri), prompting them to join the Confederacy. This would have been devastating to our nation’s capital and, perhaps, to the fate of the Union.

When the Confederacy of Southern States ultimately fired the first shots on Fort Sumter in the early hours of April 12, 1861, Anderson and his comrades valiantly defended their position until they ran out of ammunition and food, forcing them, two days later on April 14, to surrender and strike the colors of the United States of America.

As I walked the grounds of Fort Sumter, I was impressed by its isolation in the middle of Charleston Harbor. It reminded me of famous island prisons, such as Elba and Alcatraz. And I was deeply moved when the Park Service guide pointed out the fingerprints in some of the bricks lining the Fort’s walls. These impressions were made by the hands of slaves—some clearly those of children—who, many years before, were forced to manufacture the building blocks of this citadel.

Major Anderson went on to serve the Union Army admirably, rising to the rank of Brigadier General, before retiring in 1863 for reasons of health. After Lee’s surrender at Appomattox two years later, Anderson was invited to return to Fort Sumter to participate in a ceremony on April 14, 1865, where he would raise the same flag that he lowered four years ago to the day.

That night, Anderson and other dignitaries attended a dinner at a hotel in Charleston. As the evening was drawing to a close, each attendee was asked to propose a toast. When it was finally Anderson’s turn, this is what he said, according to Brad Dentzer, the author of Allegiance: Fort Sumter, Charleston, and the Beginning of the Civil War.

“I beg you now,” he said, his glass in hand, “that you will join me in drinking to the health of another man whom we all love to honor, the man who, when elected President of the United States, was compelled to reach the seat of government without an escort, but a man who now could travel all over our country with millions of hands and hearts to sustain him. I give you the good, the great, the honest man, Abraham Lincoln.”

At almost the precise moment he concluded his toast, John Wilkes Booth put a gun to the head of the President of the United States and pulled the trigger.

Devotion

On Sunday, our last full day in Charleston, we attended services at St. Philip’s Church, an Anglican parish that lays claim to being the oldest European-American religious congregation in the State. It is a magnificent structure, featuring an imposing tower and remarkable acoustics.

We were greeted warmly by all whom we encountered. When asked by a woman who sat next to me on our pew where we were from and what church we attended, I said we were from Virginia and were Latter-day Saints, aka, Mormons. She winked and then replied: “Well, we all worship the same Lord don’t we?” Yes, we do.

The subject of the day’s liturgy was the proper use of wealth during our lifetimes and the importance of caring for those in need. The call-and-response format kept everyone engaged and focused on the day’s message, along with numerous hymns sung alternately by the congregation and the choir.

Next was an excellent sermon by the Reverend Andrew R. O’Dell based on The Parable of the Unjust Steward (Luke 16:1-13), which concludes with “No servant can serve two masters, for either he will hate the one and love the other, or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon.” This echoes Matthew 12:25—“… and every city or house divided against itself shall not stand”—the biblical text employed by Abraham Lincoln in one of his greatest speeches on the evils slavery and the one that launched his political career in 1858.

But the most spiritually uplifting part of the service occurred near its conclusion when the choir, in processional between the pews, sang Will Todd’s reverential, “The Call of Wisdom.” The lyrics were written by Michael Hampel and are based on the eighth chapter of Proverbs.

The first verse, with uncanny prescience, describes the human condition of so many in the world today, and then concludes with a recurring refrain where Wisdom (aka, Jehovah) poses a question for each of us to answer:

Lord of wisdom, Lord of truth, Lord of justice, Lord of mercy;

Walk beside us down the years till we see you in your glory.

Striving to attain the heights, turning in a new direction,

Entering a lonely place, welcoming a friend or stranger.

“I am here, I am with you. I have called: do you hear me?

I am here, I am here, I am with you.”

Today, we find ourselves, to one degree or another, stranded indefinitely in “a lonely place,” deprived of the association and collegiality of our extended family, friends and co-workers. Beyond our individual households, virtually all forms of intimate contact and communal interaction—the warm embraces, the locking of arms, the gathering together in schools to learn or in sacred places to worship or to grieve when a loved one passes—have been circumscribed.

But most worrisome is the degree to which isolation has exacerbated our growing tendency to consider any worldview other than our own suspect. Instead of welcoming a stranger who looks or thinks differently, or who has the temerity to voice an opinion contrary to ours or the moral certainty du jour, we deploy virtual weapons to judge, silence, shame, and provoke him, giving little thought to the damage we are causing or the seeds of enmity we are sowing. If these shadows are not altered, the end result may not be just a house divided but one rent asunder.

Perhaps instead of boldly proclaiming in word and song, “The Lord is on our side,” we should emulate the humility and self-doubt often exhibited by Abraham Lincoln. When one of his advisors expressed his gratitude that God was on the side of the Union, Lincoln replied, “Sir, my concern is not whether God is on our side; my greatest concern is to be on God’s side, for God is always right.”

Lincoln was never tempted to forsake epistemic humility for pride, even when it was clear the Union would prevail. In lieu of taking a victory lap, he extended an invitation to all Americans: “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds….”

God, however, will not “give us to see the right” if we are about the business of inflicting wounds instead of healing them. As the sacred music of “The Call of Wisdom” reminds us, He is here, He is with us, He has called. But unless we are quiet, introspective and teachable, we will not hear Him.

As a Civil War historian, (Master’s Degree in Civil War History) I love this post. I visited Charleston last year and found it fascinating. I think the trip out to Ft Sumter is not to be missed. Two other destinations in Charleston that help one to understand Slavery are Boone Plantation and Old Slave Mart Museum . Both very worthwhile.

Good one. I enjoyed it.

Well done. We would all do well to remind ourselves frequently of Lincoln’s wisdom in seeking to be on the Lord’s side — in all things, not just in a military conflict.

Karen,

I knew this one would appeal to you. And one of our stops in Charleston was the Boone Plantation, which has been beautifully restored. I’d love to go back.

Dick,

Your observation is both astute and timely. Remembering to stay on the Lord’s side during peace and prosperity seems to be a constant struggle for the human race.

And thank you for the kind words, Brother Thorpe. Much appreciated.

Thank you for sharing “The Call of Wisdom” – it is sublime! So hauntingly lovely. I can only imagine the experience of hearing it in person in that lovely chapel. Must have been truly divine.

S Barnhart, you have described the music and the experience of hearing it in that beautiful church perfectly. The choir’s performance was superb—they even had uniforms, so you knew they we’re going to be good. 🙂

Not having heard the piece before made the experience all the more unexpected and overwhelming. I haven’t felt the spirit like that in a worship service very often in recent years.