Throughout history, most societies have embraced the notion of an afterlife where the spirits of the dead reside. Such a belief frequently spurs the living to find ways to stay in touch, or otherwise maintain a connection, with those who have gone before. And some cultures do it in unique ways.

Mormons, for example, perform religious rituals in their temples on behalf of their ancestors, believing those ordinances will cement familial bonds through the eternities. The Catholic Church—until the Reformation quashed the practice—offered intercessory prayers and elaborate masses for the departed. Today, adherents of Catholicism frequently look to those beyond the veil (Saints) for assistance with matters in their daily lives.

The idea that the world of the dead intersects with our own finds expression around the world, from Mexico’s Day of the Dead to Japan’s Bon festival. On these special occasions, families gather in their homes, houses of worship, and sometimes cemeteries, to eat, drink and commune with their forefathers. But one of the most imaginative and remarkable forms of preserving these ties was practiced for thousands of years, until around 1500 A.D., by the inhabitants of Peru, who not only conversed with the dead, but did so in person with their departed ancestors physically present.

According to the author Neil MacGregor, the British Museum (where he was the Director for thirteen years) has in its collection several “packages” wrapped in dull brown cloth, each one about three feet in length, carefully enveloped and bound.[1]

According to Jago Cooper, head of the Americas section at the Museum:

These are mummy bundles from Peru, containing the remains of ancestors of the people that live there today. Inside each bundle is a mummified body, meticulously prepared and wrapped in textiles. It is a practice which went on for more than 6,000 years in Peru and northern Chile, and it enabled these ancestors to play a posthumous role in society completely different from any that we in Europe could imagine for our forebears—or for ourselves.

The Peruvian practice of mummification appears to be as old as its Egyptian counterpart. At the time of death, “the soft tissue would be removed and the body usually placed in a crouching position before being wrapped.”[2] Also, painted faces—presumably bearing a likeness to the deceased—were attached to these bundles as a clear reminder that these were real people. But, as Neil MacGregor explains, “Peruvian mummies … had an altogether livelier after-life” than the cadavers in Egypt.[3]

For important meetings and celebrations they were displayed and honored—and invited to participate in the affairs of the community. In this manner, according to Cooper, they established the bona fides of their descendants: “To have your distinguished ancestor with you at the table during an important meeting was to proclaim your lineage and your ancestry: descent from them by direct bloodline was the basis of your claim to power. You were heir not just to that person but to their wisdom, power and authority.”[4]

Cooper goes on to explain that the cultural impact of this practice went far beyond the mere veneration of the dead. It altered the community’s perception of time.

For us, when our ancestors die, they are in the past and our descendants are in the future. For the Inca and many cultures of the Americas, the thinking was—and often still is—fundamentally different. For them all time is together: the present, future and past exist concurrently, are always running parallel, and it is possible, with skill, or sometimes in a trance, to move between the different times, and draw on the insights that all three can offer.

In other words, not only would the mummy bundles contribute to the conversation of the day, the spirits of those not yet born would be part of the debate. “They too would help shape political decisions, in which they had such a large stake.”[5]

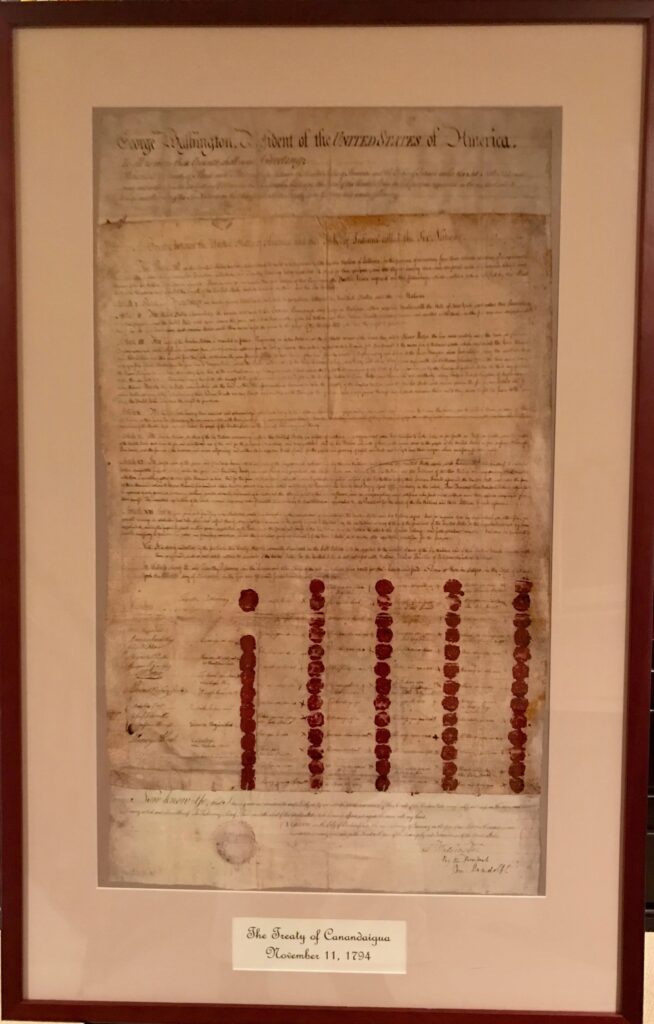

I have personally witnessed a similar phenomenon in my legal representation of Indian tribes located in the Eastern United States. When I was retained by the Oneida Nation of New York in the early 1990s, I was told about the Treaty of Canandaigua, an agreement among the Oneidas, other members of Iroquois Confederacy, and the United States, bearing the signature of George Washington, that is still in force and effect.

I initially thought this was a remarkable, albeit quaint, bit of U.S. history. I soon learned, however, that, for the Oneidas, this treaty wasn’t signed 225 years ago; rather, the members of the tribe speak of it as if it had been executed yesterday. For the Oneidas, this is not history; it’s part of their lifeblood. The treaty’s guarantee to the Nation of the free use and enjoyment of its land free from interference by the United States—a promise, sadly, more often honored in the breach than in the observance—affects how they perceive and interact with the rest of the world.

This mindset—merging the past with the present—is a product, in part, of their oral traditions. Unlike western governments, they do not have a written constitution nor do they hold elections. Rather, their leaders govern by consensus, and when they make important decisions, they often turn to their elders, the repository of tribal culture, history and traditions. When these wisdom keepers speak, they invoke the spirits of the tribe’s ancestors, whose presence can sometimes be felt. I have had the privilege of sitting in the Nation’s most sacred space, its longhouse, during such a meeting.

But, like their Peruvian brothers in the Southern Hemisphere, the wisdom of the tribe’s elders is not the final word. Rather, one question remains to be considered: “How will our actions today impact the seventh generation to come?” To help preserve these generational bonds and oral traditions, the Oneidas have constructed a beautiful Children and Elders Center, where the youngest and oldest generations can learn from each other and the tribal elders can discharge their responsibility of handing down the spiritual teachings and customs of the Nation to the children.

The importance of maintaining a proper balance between the wisdom and traditions of our ancestors, our desire to build a better world, and the interests of our posterity was appreciated not only by the ancient Peruvians but also by many native peoples in North America—and, as MacGregor notes, some of our European forefathers. The brilliant Irish statesman and philosopher, Edmund Burke, in his Reflections on the Revolution in France, gave eloquent expression to the imperative of generational interdependence:

Society is … a partnership in every virtue, and in all perfection. As the ends of such a partnership cannot be obtained in many generations, it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.

Only thirteen years separated the American Revolution and its French counterpart, two movements premised on the same principles: Liberty and Equality. The former, which preserved the positive elements of its heritage, such as the British Common Law and the idea of representational government, gave the world a functioning democracy and George Washington; the latter, which obliterated its past by assassinating the monarchy, ravaging the churches, and repudiating cultural norms, spawned The Terror and Napoleon Bonaparte. The wisdom of the Incas, the Oneidas and Mr. Burke command our attention.

[1] MacGregor, Neil, Living with the Gods, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018), p. 84.

[2] Ibid, p. 85.

[3] Ibid, p. 86.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, p. 87.

Great summary paragraph to pull it all together. Thanks.

I think the idea of linear time is a product that exists only because that is what we understand. I actually think of time more like a circle. Or, of time as having no tomorrow, today, or yesterday. It is then like one big painting.

Therefore I find other civilizations that moved beyond linear time interesting and not surprising.

Also I second my husband’s comment above.