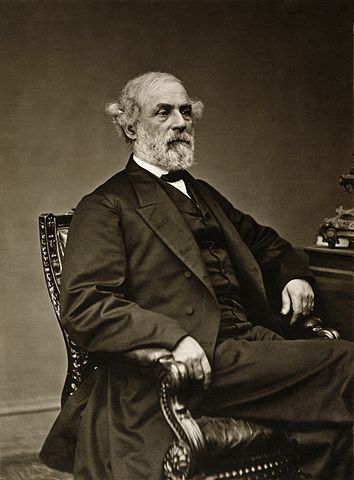

Never in the history of the United States has public opinion changed so swiftly regarding an historical figure—absent the discovery of new information about the individual’s character or actions—than is the case with Robert E. Lee.

Almost instantly after his surrender, he became “universally admired even by those who had no sympathy toward the cause for which he fought.”[1] These sentiments also prevailed throughout the 20th century. Teddy Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Ronald Regan and countless others held him in high esteem. He was, according, to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “one of our great American Christians and one of our greatest American gentlemen.”[2] Winston Churchill wrote that Lee was “one of the noblest Americans who ever lived, and one of the greatest captains known to the annals of war.”[3]

But in the words of the author Christopher Caldwell, “as the present generation has radicalized around race ideologies, opinion has become more frenzied and passionate than it has been since the height of the Civil War.”[4] Today, expressing opinions about Lee, such as those voiced by FDR and Churchill, can get you shamed, cancelled, and perhaps even fired.

Robert E. Lee is worthy of neither deification nor demonization. He was an inordinately complex individual whose flaws and virtues warrant careful examination. But objectivity can only be preserved if we endeavor to view the world through his eyes, not from the perspective of someone who knows how the story ends or whose culture is markedly different from the society Lee inhabited. In the words of the esteemed historian, Gordon Wood, we must be committed “to objective truth and the pastness of the past.”[5] Otherwise our history is distorted and nothing more than partisan propaganda.

Beginnings

Robert E. Lee was born on January 9, 1807, in Stratford Hall, Virginia. But he was hardly the first Lee to arrive in the Old Dominion. His great uncle, Richard Lee, emigrated to Virginia almost 190 years before, just two decades after the first British settlers arrived in Jamestown.

Lee’s ancestors were powerful and influential individuals in the New World, serving as members of the Virginia colonial legislature, delegates to the Continental Congress, signers of the Declaration of Independence, and officers in the Revolutionary War.[6] But then, at perhaps the worst possible moment, a black sheep joined the ancestral line: Henry Lee III, known as “Light Horse Harry.” He was Robert E. Lee’s father.[7]

Henry Lee III, was a graduate of Princeton, served with distinction as a calvary officer during the War for Independence, and then as Governor of Virginia. But then he disintegrated. He managed to antagonize his political opponents, and his land speculation and other wild investment schemes landed him in debtor’s prison. When he was released, he decamped to the West Indies, abandoning his second wife and their five children. The following year, he died. Robert was six-years old.[8]

Though Lee had few memories of his father, he was haunted by the man’s legacy of dishonesty and financial irresponsibility. Robert vowed he would be nothing like him. He expected perfection of himself and demanded it of those around him. He strove to pattern his life after George Washington, who was a friend and benefactor of his father. And Lee found a familial connection with the Father of Our Country through his wife, Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee, who was the step-great-granddaughter of George Washington.

He sought financial security through a military career, which began at West Point. He graduated second in his class with no demerits, one of the few cadets in the history of the institution without a blemish on his record.[9]

Lee began his career with the Army Corp. of Engineers, the most selective branch of the military at that time. While there, he was assigned to some of the largest and most challenging public works projects, including the creation of a channel in the Mississippi River, opening St. Louis to shipping, which was a boon to the city’s economy.[10]

When the opportunity for a combat assignment presented itself, he put aside his slide rule and surveyor’s tools and headed south of the border where he served with great courage, stamina and distinction in the Mexican War. He became close friends with Winfield Scott, the Commanding General of the United States Army, who sang Lee’s praises to Congress.[11] Lee then returned to active duty in the southwest.

In 1857, while stationed in San Antonio, Texas, Lee received word that that his father-in-law, George Washington Custis, had died and that he was named executor of the man’s estate. Lee sought, and was granted, leave to return home to his bereaved wife and children where he would be compelled to assume new—and unwanted—responsibilities.[12]

Slavery

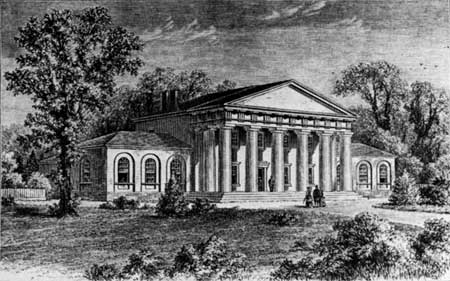

Home for Lee and his family was the Arlington House in Alexandria, Virginia. A prominent landmark with a majestic view of Washington. Today, it is under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service and has been renamed the Robert E. Lee Memorial.

Upon his arrival, Lee learned four unpleasant things about Custis’ estate. First, the man had owned three large Virginia plantations, all of which were in a state of disrepair. Second, these estates were staffed by approximately 190 slaves who generally neglected their duties in favor of tending to their own gardens and otherwise doing as they pleased.[13] Third, Custis left virtually nothing to Lee, though he and his wife were allowed to remain at Arlington House until she died. And finally, as executor Lee would be required to free all of Custis’ slaves in five years while simultaneously generating enough income to make $10,000 bequests to each of his five daughters—$1.6 million today’s currency—as mandated by the will.

Lee himself owned only four slaves, which he had inherited from his mother, and regarded slavery as “a moral and political evil.”[14] Modern-day critics are quick to note that Lee believed it was “a greater evil to the white man than the black race.” But this was the common attitude of a pious Christian at the time: the sin first pollutes the sinner before harming those around him. Thus, Lee’s mindset is consistent with thinking that slaveholding is abhorrent in the eyes of God.

Lee funded the expatriation of slaves from Arlington who were willing to settle in Liberia,[15] a venture Lincoln also enthusiastically supported for a time.[16] Like his father-in-law, he saw to their education, both religious and secular, which was a direct violation of Virginia law.[17] Indeed, Booker T. Washington, an educator, author and adviser to multiple presidents, and who was born into slavery, credits Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson with being the first white people to display an abiding interest in the religious education of blacks. “Where Robert E. Lee and ‘Stonewall’ Jackson have led in the redemption of the negro through the Sunday-school,” Washington said, “the rest of us can afford to follow.”[18] Washington, who was the dominant leader in the African-American Community of his day, did not allow his hatred of the cause for which Lee fought to blind him to the man’s virtues.

It is fashionable today to portray Lee as a horrific taskmaster, who leased out his slaves to neighboring plantations and routinely beat his charges. But leasing slaves was a common and legal practice in Virginia, one Lee believed was necessary in order to fulfill the terms of Custis’ will.

As to Lee’s alleged penchant for violence, there is only one documented case of Lee whipping the slaves entrusted in his care—one some historians are not inclined to believe—and this allegedly occurred after the three slaves in question tried to escape. Corporal punishment of slaves—and children—was quite common and quite legal in 19th century America. And given the lax discipline that prevailed on the Custis estates, it’s not surprising that the slaves viewed Lee as cruel. They resented his efforts to make the plantations profitable, an enterprise whose success depended upon their labor.[19]

In reality, Lee and his wife Mary entrusted both their possessions and their children to their slaves. And both the Custis and Lee families worshiped together with their slaves on Sundays.[20] Even Elizabeth Brown Pryor, one of Lee’s harshest modern critics, concedes that Lee’s behavior as Custis’ executor was in most respects exemplary.[21] He actually lost money while fulfilling his duties as estate administrator and succeeded in freeing all of his father-in-law’s slaves by 1862. Simultaneously, he voluntarily manumitted his own slaves.

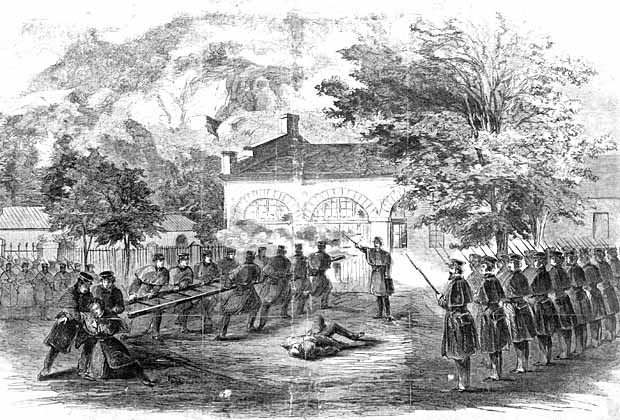

In October 1859, while in the midst of managing the chaos at Arlington House, Colonel Robert E. Lee received orders to repair to Harpers Ferry to deal with an unexpected problem. John Brown and twenty of his comrades were attempting to seize control of the federal armory for purposes of inciting a slave rebellion throughout the South. Upon his arrival, Lee quickly suppressed Brown’s quixotic insurrection, capturing him and those of his comrades who had not been killed in the process.[22]

Though Brown failed to instigate a slave uprising, he succeeded in irreparably severing the country in two halves, rendering the secession that occurred after Lincoln’s election the following year a mere formality. Little did he know that his captor would soon hold the fate of the Confederate South in his hands.

Decisions

In February of 1860, Lee returned to his command in Fort Mason, San Antonio where he nervously watched the presidential campaign unfolding. The Democrats fielded two pro-slavery candidates—Stephen A. Douglas and John C. Breckenridge—who threatened to split the vote, thereby assuring a Lincoln victory. Since neither man was willing to withdraw, they made good on that threat. Six weeks after Lincoln captured the presidency, South Carolina became the first state to secede.

Lee abhorred secession, calling it “revolution” and “anarchy.” In his mind, no greater “calamity” could befall the “country than the dissolution of the union.”[23] But unless Lincoln was willing to allow slavery in the western territories, Lee believed it was inevitable. Lee, of course, knew that Lincoln would never consent to the expansion of slavery since he had campaigned against it. Lee’s hatred of slavery is not inconsistent with his willingness to see it grow if, by doing so, it preserved the union.[24] Nevertheless, his predisposition to preserve the status quo in exchange for the proliferation of the South’s “peculiar institution” is difficult to defend.

In late February, 1861, Lee was ordered to return to Washington to meet with the General-in-Chief, Winfield Scott. During his first meeting with Scott, he made it clear he would make no decision regarding his future in the United States Army until his home state decided whether or not to secede. The members of the Virginia Convention, on April 4th, took a test vote, and the results were 2-1 against secession,[25] so it looked, ever so briefly, like Lee would be spared having to choose between Virginia and the Union.

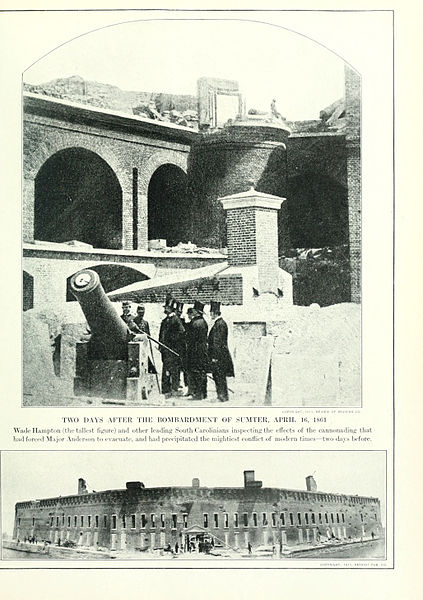

But on April 12, Fort Sumter was attacked and forced to surrender two days later, by South Carolina’s militia. Lee was then summoned again to Scott’s office and offered the command of all Union forces with the rank of major general. Lee declined, which should surprise no one. After making it clear that his refusal had nothing to do with defending slavery, he said “I can not raise my hand against my children” nor even “oppose [my] native state.”[26]

Shortly thereafter Lee made a second fateful decision: he resigned his commission as a full colonel in the United States Army. The Virginia Convention then reversed course, electing to secede by a narrow margin. Lee was now presented with a third decision: would he accept a high-ranking command in the Confederate Army? As of yet, there was no clear indication that he would, especially since Virginia, while having seceded, had not yet decided whether to join the Confederacy or stand alone as a new constitutional republic.[27]

A delegation from Richmond was dispatched to Arlington to persuade Lee to take command of the forces of the Commonwealth. He was noncommittal but nevertheless was willing to consider the proposition. His cousin, Cassius, urged him to accept the appointment, for doing so might lead to the “peaceful settlement of our troubles.”[28] While this may strike us as delusional, Winfield Scott himself told Lee that he thought Lincoln would ultimately recede and reach a peaceful accommodation with the southern states. Indeed, two years into the war an Austrian observer of the conflict was surprised to learn that most politicians did not believe war would inevitably follow secession.[29] So Lee had reason to hope that he might help facilitate a nonviolent resolution of the standoff.

Lee agreed to travel to Richmond and meet with state officials to discuss the matter further. Towards the end of April, he accepted, albeit unenthusiastically, command of Virginia’s forces. Several days later, Virginia elected to join the Confederate States. And war came.

Postbellum

Almost exactly four years to the day when the first shots were fired on Fort Sumter, the Civil War effectively came to an end with Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. He has been rightly praised for accepting the results as the defeated party, especially in the face of pressure from Jefferson Davis and others to scatter his troops and conduct a guerilla war. He urged his men to lay down their arms, return to their homes and tend to their farms. “For us, as a Christian people, there is now but one course to pursue. We must accept the situation … and proceed to build up our country on a new basis.”[30]

After the war, Lee’s opinion regarding the black race did not change; he believed them incapable of self-government. In this his views, were similar to those of Lincoln before the war,[31] though, by its conclusion, Lincoln’s opinions had begun to change. In judging Lee, we should bear in mind, as the scholar John McWhorter has observed, that it “is very hard to see beyond what is normal in your time. Someone who grew up seeing black people as almost nothing but unpaid servants could not help but process this as normal, was vanishingly unlikely to argue against it, and—yes—likely ended up thinking of black people as inherently inferior.”[32]

Lee also was criticized for not speaking out against those who ignored his injunction to turn their swords into plowshares and for failing to condemn those who persecuted their former slaves. But doing so would have been totally out of character. Lee was an intensely private man, one who preferred to lead by example.

A few weeks after the end of the war, during Sunday services at an Episcopal Church in Richmond, the minister was flummoxed when the first person to kneel to receive communion was a black man. African-Americans were expected to wait until all white congregants had partaken, and the priest didn’t know what to do. The impasse was resolved when Robert E. Lee came forward to the chancel and knelt with quiet dignity along the same rail as the black man. The rest of the congregation—both black and white—then came forward and did likewise.[33]

Similarly, while serving as President of Washington College after the war, Lee learned that a student, as a college exercise, delivered an oration in which he eulogized the “Lost Cause” and what it meant. When word of this found its way to Lee, he sent for the student. While complimenting him on his composition and delivery, he “seriously warned him against holding or advancing such views, impressing strongly upon him the unity of the Nation, and urging him to maintain the integrity and honor of the United States.”[34]

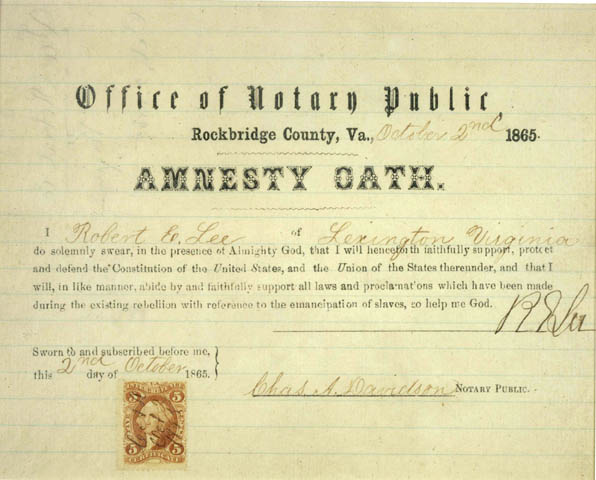

Was Lee guilty of treason? As that term is defined in the Constitution, the answer would appear to be yes. But the oath Lee took as an officer—which was changed in 1862—creates an ambiguity. He pledged his “allegiance to the United States of America, and to faithfully serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatever…” (emphasis added).[35] This is not surprising since before the war the two words “United States” were considered a plural noun: “the United States are a republic (emphasis added).”[36] Thus, one could conclude—as many did—that loyalty to one’s state was paramount, or at the very least equal to one’s loyalty to the federal government. It is worth noting that John Brown, for his assault on the Federal Armory in Harper’s Ferry, was tried, convicted and executed for the crime of treason not against the United States but the Commonwealth of Virginia.[37]

In a very real sense, this was not a civil war but a war between two nations, two regions who failed to come together as a single political entity because, at the time they agreed upon a constitution, they were unable to permanently resolve the most divisive issue on the table: slavery. For this reason, the Civil War has often been described as a “second founding.”

There is one question Lee’s detractors invariably fail to ask: What would have happened if Lee had chosen to sit out the war? Many historians believe that there would have been no Civil War, only a brief rebellion quickly suppressed. At the time Lee took command of Virginia’s forces, there was no Confederate Army, only militias whose first allegiance was to their home state.

If it hadn’t been for Lee’s organizational skills and tactical genius, then McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862 likely would have resulted in the capture of Richmond, the Confederate capital.[38] The collapse of the Confederacy would have soon followed since Union forces had already penetrated deep into western Tennessee and the Mississippi Valley. In all probability the seceded states would have returned to the union with slavery intact for who knows how long.[39]

Shortly after he had decided to cast his lot with the Confederacy, Lee had a premonition that the slavery he so despised but was willing to defend was the raison d’être for the coming conflagration: “I foresee the country will have to pass through a terrible ordeal, a necessary expiation perhaps for our national sins.”[40] There was a time when we would have made room for the hand of Providence in circumstances such as these. Not so today.

Indeed, our current environment is one of rabid iconoclasm pursued with missionary zeal. And it is not just Robert E. Lee who has been driven from the public square. Statues of Jefferson and Theodore Roosevelt recently met their demise in New York City,[41] while a committee formed by the mayor of the District of Columbia has proposed that the federal government “remove, relocate, or contextualize” the Washington Monument (relocate?!?).[42] Woodrow Wilson is no longer welcome at Princeton where he was President of the University, and the San Francisco renaming committee proposed removing Lincoln’s name from a local high school because our Sixteenth President, “like the presidents before him and the most after, did not show through policy or rhetoric that Black lives ever mattered to them….”[43]

This mindset bears a striking resemblance to that of the French Revolution, where all that had come before—the monarchy, rule of law, religion, even the seven-day calendar—was to be swept away and the country completely cleansed. This is a characteristic of virtually all utopian dreams, which are premised on the notion that human nature can be changed. But it cannot,[44] something Abraham Lincoln understood with clarity and conviction. And with that understanding, he charted the only way forward as the Civil War was drawing to a close:

“Human nature will not change. In any future great national trial, compared with the men of this, we shall have as weak and as strong; as silly and as wise; as bad and as good. Let us, therefore, study the incidents of this, as philosophy to learn wisdom from, and none of them as wrongs to be revenged.”

Abraham Lincoln, Speeches, Letters, and Miscellaneous Writings Presidential Messages and Proclamations, “Response to a Serenade, Washington, D.C.,” November 10, 1864, (New York, New York: The Library of America, 1989), p. 641.

Mercy and forgiveness guided Lincoln’s decision to allow those who had fought for the south to return to their homes and to the Union. And that belief in redemption was on full display when Ulysses S. Grant “vehemently” opposed President Andrew Johnson’s attempt to indict Robert E. Lee for treason, threatening to resign his commission if Lee were arrested.[45] Ultimately, he was pardoned in 1868 under a general amnesty.

But Lee’s civil liberties were not fully restored because his Oath of Allegiance had been lost, apparently “misplaced” by the malevolent Johnson. When it was discovered in the early 1970s, Congress passed, and President Ford signed, legislation restoring Lee’s citizenship rights. The margin of victory speaks volumes: the vote was unanimous in the Senate and 407 to 10 in the House.

In his remarks upon signing the legislation, Ford praised Lee’s exemplary character and highlighted how Lee, after the war, repeatedly stressed the importance of uniting the country and restoring peace and harmony.[46] How ironic then that those embroiled today in the battle over Robert E. Lee’s place in our history and society—and the place of many other public figures from the past—are doing their best, deliberately at times it seems, to divide our country.

While Robert Edward Lee does not deserve our breathless adoration, he does deserve our respect.

[1] Michael Korda, Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee, (New York, New York: HarperCollins, 2014) p. 671.

[2] Ty Seidule, Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerners Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause, (New York, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2020), p. 171.

[3] H.W. Crocker III, Robert E. Lee on Leadership: Executive Lessons in Character Courage and Vision, (New York, New York: Three Rivers Press, 1999) p. 4.

[4] Caldwell, Christopher, “There Goes Robert E. Lee,” Claremont Review of Books, Spring 2021, p. 75.

[5] Gordon S. Wood, Power and Liberty: Constitutionalism in the American Revolution, (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), p. 9.

[6] Michael Korda, Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee, (New York, New York: HarperCollins, 2014), pp. 3-5.

[7] Allen Guelzo, Robert E. Lee: A Life, (New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2021), p. 6.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Korda, p. 26.

[10] Ibid, p. 49.

[11] Ibid, p. 129.

[12] Guelzo, pp. 151-155.

[13] Ibid, p. 202.

[14] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 281.

[15] Guelzo, p. 6.

[16] Korda, p. 68.

[17] Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters, (New York, New York: Penguin Group, 2007), p. 134.

[18] Organized Sunday School Work in America: 1905-1908, (Chicago, Illinois: Executive Committee of the Int’l Sunday-School Association, 1908), p. 556.

[19] Korda, p. 202.

[21] Ibid, p. 262.

[22] Korda, pp. xvi to xl.

[23] Guelzo, pp. 178-179

[24] Korda, pp. 217-221.

[25] Ibid, p. 226.

[26] Guelzo, pp. 186-188.

[27] Guelzo, p. 194.

[28] Guelzo, p. 195.

[29] FitzGerald Ross, Cities and Camps of the Confederate States, ed. Richard B. Harwell (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1958), p. 178.

[30] Charles F. Adams, Lee at Appomattox and Other Papers, (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1902), pp. 11-12.

[31] Korda, p. 68.

[32] John McWhorter, Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America, (New York, New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2021), p. 133.

[33] Jay Winik, April 1865: The Month That Saved America, (New York, New York: HaperCollins, 2001), pp. 362-363.

[34] Adams, pp. 422-423.

[35] Guelzo, p. 47.

[36] McPherson, James, “Out of War, A New Nation,” Prologue Magazine, Spring 2010, Vol. 42, No. 1,

[37] Evan Carton, Patriotic Treason: John Brown and the Soul of America, (New York, New York: Free Press, 2006), p. 324.

[38] Aaron Sheehan-Dean ed., The Cambridge History of the American Civil War: Vol. 1: Military Affairs, (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2019), pp. 72-94.

[39] See, e.g., Katherine Calos, “Civil War 150th: If war had ended in Richmond, slavery issue would have been unresolved,” Richmond Times Dispatch, May 6, 2012 (interview with Ed Ayers, University of Richmond President and historian of the American South), https://richmond.com/news/civil-war-150th-if-war-had-ended-in-richmond-slavery-issue-would-have-been-unresolved/article_44914b3f-1a2a-572e-95af-e812b3c59f55.html (accessed January 29, 2022).

[40] McPherson, p. 281.

[41] Adela Suliman, “Theodore Roosevelt statue removed from outside New York’s Museum of Natural History,” The Washington Post, January 20, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/01/20/theodore-roosevelt-statue-new-york/ (accessed January 29, 2022).

[42] Jonathan Horn, ‘Travels With George’ Review: A President Hits the Road,” The Wall Street Journal, September 10, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/travels-with-george-nathaniel-philbrick-review-a-president-hits-the-road-washington-11631287810 (accessed January 29, 2022).

[43] Jill Tucker, “Abraham Lincoln, once a hero, is now a bad guy in some S.F. education circles,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 13, 2020, https://www.sfchronicle.com/local-politics/article/Abraham-Lincoln-was-once-a-hero-In-some-S-F-15798744.php (accessed January 29, 2022).

[44] See Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature, (New York, New York: Penguin Books, 2002). For a brilliant analysis of how different perceptions of human nature are at the heart of most all political disagreements, see Thomas Sowell, A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles, (New York, New York: Basic Books, 2002).

[45] John Reeves, The Lost Indictment of Robert E. Lee: The Forgotten Case against an American Icon, (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), p. 80.

[46] Gerald R. Ford, “Remarks Upon Signing a Bill Restoring Rights of Citizenship to General Robert E, Lee” August 5, 1975, https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/speeches/750473.htm (accessed January 29, 2022).

Great Great piece. One of the biggest problems in studying history is “historiography” where you see historical events through morals and attitudes of your own time. “In October 1959” You may want to correct 1959 for John Brown to 1859. Also I disagree that John Brown, who was an extremist and an insurrectionist, was a main cause of the division of the Civil War. “he succeeded in irreparably severing the country in two halves.” He was one of many sidelights. (With a Master’s degree in Civil War History I don’t agree with that conclusion) Two different philosophies of what the Union should be, one featuring States Rights and an Agrarian economy and one emphasizing more Federal control and industrialization, were constantly battling against each other during the years prior to the civil war. This same battle is seen in the Constitutional Convention and the ratification of the Constitution. Neither side wants to give up influence or power and as the South’s one time equal dominance waned, a conflict or break up was inevitable. It is a mistake to always think that Slavery caused the Civil War. It very well could have happened without slavery. See Richard N Current my major professor at the U of Wisconsin. Some good biographies include ROBERT E LEE by Emory M. Thomas and the biography by Allen Guelzo. There are a good number of other biographies as well. I like and agree with your conclusion “While Robert Edward Lee does not deserve our breathless adoration, he does deserve our respect.” and think all the renaming and rejection of the past is a product of today’s mob rule. As the wife of Richard Lee Hanneman I have a real fondness for someone named Lee. We are really “throwing out the baby with the bath water” so to speak.

This is very well done. In today’s overheated environment, it is the rare writer who views history as a quest for truth, rather than as a weapon to be wielded in today’s partisan battles.

I don’t have much of substance to add to you nuanced and interesting essay, except to call your attention to the testimony of Lee before Congress on February 17, 1866 (you might well already be aware of this). I find this testimony very useful in reorienting my modern mind to the issues as they were actually being discussed in the immediate post-war environment.

https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/robert-e-lees-testimony-before-congress-february-17-1866/

I found the concluding portion of Lee’s testimony particularly fascinating:

Question. Has there been any considerable change in the number of the negro population in Virginia during the last four years?

Answer. I suppose it has diminished, but I do not know.

Question. Diminished in consequence of more negroes going south than was made up by the natural increase?

Answer. My general opinion is that the number has diminished, and for the reason yon give.

Question. I suppose that the mass of the negroes in Virginia, at the present time, are able to work; that there are not many helpless ones among them?

Answer. There are helpless ones, certainly, but I do not know to what extent.

Question. What is your opinion about its being an advantage to Virginia to keep them there at all. Do you not think that Virginia would be better off if the colored population were to go to Alabama, Louisiana, and the other southern States?

Answer. I think it would be better for Virginia if she could get rid of them. That is no new opinion with me. I have always thought so, and have always been in favor of emancipation—gradual emancipation.

Question. As a question of labor alone, do you not think that the labor which would flow into Virginia, if the negroes left it for the cotton States, would be far more advantageous to the State and to its future prosperity?

Answer. I think it would be for the benefit of Virginia, and I believe that everybody there would be willing to aid it.

Question. Do you not think that the State of Virginia is absolutely injured and its future impaired by the presence of the black population there?

Answer. I think it is.

Question. And do you not think it is peculiarly adapted to the quality of labor which would flow into it, from its great natural resources, in case it was made more attractive by the absence of the colored race?

Answer. I do.

Very well written. Certainly captures what we would consider the “complexities” of Robert E. Lee.

However, I believe a large percentage of the “complexities” are only made complex because we insist on viewing the man outside of the context of his time. In context, it is not difficult to understand why Lee thought what he thought or behaved in the way he behaved. That doesn’t make it “right” or “excuse” the actions that he took that we now see as immoral. But, it should give us pause when we attempt put ourselves on a moral plane above him. How many of us, placed in those same circumstances would have lived a “better” life? In the end, he was a man of many admirable qualities and also some obvious faults. The impact he was able to have on his society was extraordinary (for better or worse). He may not deserve to be adored or condemned, but he deserves to be remembered.

Thank you for feedback, Karen; it is always thought provoking. And thanks for catching the typo. I’m surprised there weren’t more!

I relied quite heavily on Guelzo’s biography when doing research for this essay, along the one authored a few years ago by Michael Korda. Pryor’s biography, and a few others I consulted, were also very helpful. And Charles Adams has written some insightful essays about Lee. There is no shortage of information and opinions about the man.