“What’s in a name?” Juliet rhetorically asks in reference to Romeo’s clan: the Montagues. The answer, as she would soon learn, is: “quite a lot.” And in the world of the Old Testament, names were hugely important.

The creation story underscores its significance when God gives a name to our world and to each of its features and inhabitants. For the Israelites, your name was an essential part of your individuality and created a link between you, your ancestors and descendants, preserving your connection with the living even after you have departed.

But a name poorly chosen can confuse and conceal; and the lack of a name can sheer you of your identity. Each of these themes is found in the first nine verses of chapter 11 of Genesis, a story commonly known as “The Tower of Babel:”

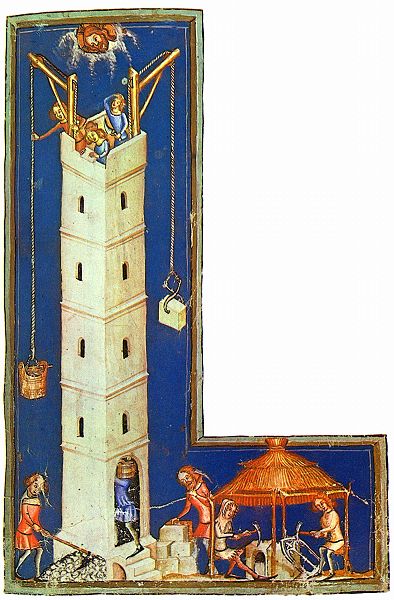

1 And all the earth was one language, one set of words. 2 And it happened as they journeyed from the east, that they found a valley in the land of Shinar and settled there. 3 And they said to each other, “Come, let us bake bricks and burn them hard.” And the brick served as stone, and bitumen served as mortar. 4 And they said, “Come, let us build us a city and a tower with its top in the heavens, that we may make us a name, lest we be scattered over all the earth.”

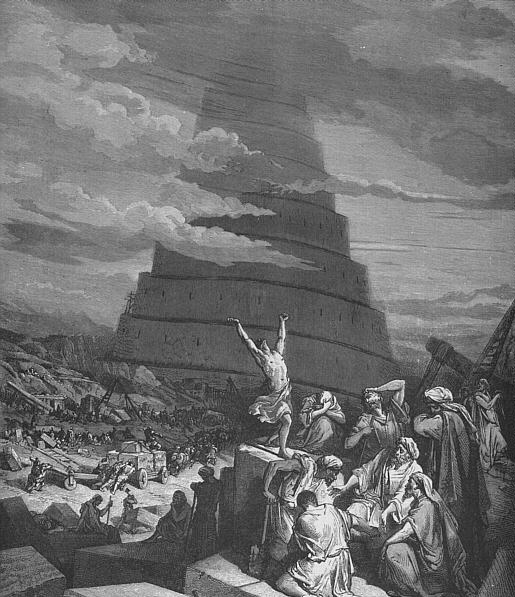

5 The Lord came down to see the city and the tower that the human creatures had built. 6 And the Lord said, “As one people with one language for all, if this is what they have begun to do, now nothing they plot to do will elude them. 7 Come, let us go down and baffle their language there so that they will not understand each other’s language.” 8 And the Lord scattered them from there over all the earth and they left off building the city. 9 Therefore it was called Babel, for there the Lord made the language of all the earth babble. And from there the Lord scattered them over all the earth.

The Five Books of Moses, trans. Robert Alter (W.W. Norton and Company, Inc.: New York, New York, 2004), p. 58.

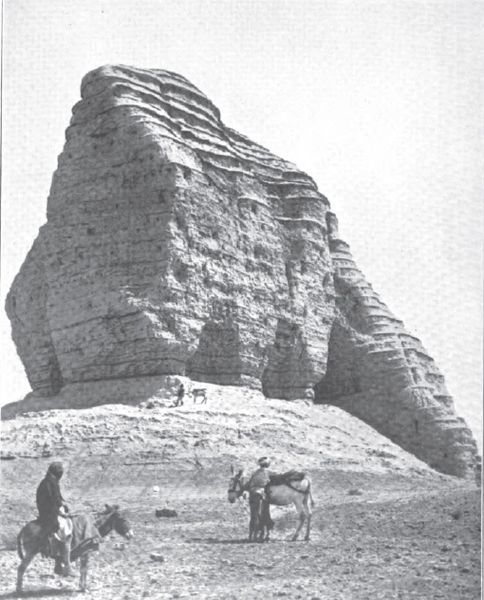

This story is given only cursory attention in our church, and when it is discussed, the traditional interpretation is parroted: the building of the tower was a hubristic attempt to scale the heights of heaven, an act that displeased God.[1] But the text does not support that reading. The reference to “a tower with its top in the heavens” is a hyperbole commonly found in Mesopotamian inscriptions for celebrating tall structures, such as ziggurats.[2] It does not connote finding a back door to paradise.

And our understanding of this story is further hindered by the name given to it: The Tower of Babel. In actuality, this tale has little or nothing to do with the tower. Rather, its focus is on the city and its people, who have offended God, though the nature of their offense is not readily apparent.

The telling of this story is done tersely, with no descriptive adjectives. Further, it is mind-numbingly redundant, repeating certain words and phrases over and over (just like this sentence). For example, the phrase “all the earth” appears five times as does the word “language.”

And there are no proper nouns, save “Lord” and the name given to the city in the final verse. The human characters are all nameless and faceless, devoid of personality. In sum, it is passionless and robotic. But, these same stylistic elements are the means by which the author subtly conveys the story’s meaning.

Taken together, according to Jewish scholar Judy Klitsner, they suggest a strong emphasis on “the human drive for indivisibility,” one born, in this instance, out of fear that, if they do not stand united, they will be conquered and scattered across the earth.[3] Thus, they collectively summon each other: “Come, let us build us a city and a tower.”

Note that the city is mentioned before the tower, and it is referenced three times in the text, while the word “tower” appears only twice. Their fear of dispersal can only be calmed by walling-off the outside world. This reading of the story is reinforced when God obstructs the building of the city—but makes no reference to the tower—and then gives the town a pejorative name while attaching no label to the edifice.

All of this is quite interesting, but it doesn’t answer the question: Why is God angry with the inhabitants of this city? Aren’t their united efforts to protect themselves laudable given the world in which they live?

The answer lies in what appears to be a redundancy—but actually is not—in the first verse of this story: “And all the earth was one language, one set of words.” The Hebrew term for “words,” devarim, can mean words, deeds, or things such as “ideas.” This implies, according to the 19th century Jewish scholar Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin, a strict ideological consensus among the people, one that countenanced no deviation, no doubts, no questioning.[4]

Thus, what they sought was not unity but uniformity, which manifested itself as a coercive society that wanted only to make a name for the group, which would then become the name by which each of them would be known. The tower’s purpose was to give advance warning of a threatened intrusion by foreigners who might corrupt their culture and belief system.

Note that the first call to the people is to simply come and build bricks of clay and “burn them hard,” a slow, arduous and tedious exercise—but they are not told why. Only later are they informed of the purpose of this activity: to build a city and a tower. Keeping them in the dark as to the details of the enterprise minimizes their role and significance. Sacrificing their individuality at the altar of conformity is a small price to pay, they believed, for security.

As Latter-day Saints, we can see the similarity between the behavior of the inhabitants of Babel and the plan offered by Lucifer in the pre-existence before the great council in heaven. No wonder God is furious. Their behavior threatens his chosen plan and goes against everything he has thus far done and commanded, as chronicled in the first ten chapters of Genesis.

He created man and woman after his own image, who, after partaking of the forbidden fruit, “became like one of the gods, knowing good from evil.”[5] Critical to the Father’s plan for his children is their development as unique individuals, even though their agency would inevitably result in transgressions and the need for a redeemer to atone for their mistakes. But even a rebellious individual has more in common with God than a mindless member of a human herd. Having been effaced as individuals, the inhabitants of Babel lost both their agency and their ability to covenant with the Father.

The denizens of this city also flouted the Lord’s command to “be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it,”[6]one that he repeated to Noah and his sons after the floodwaters had receded.[7] With their disobedience, they forfeited their right to choose where and how they would fill the earth; thus, they were scattered and their languages were confused so as to constrain their ability to reunite and restart their efforts to build a coercive, monolithic society.

And yet, this threat persists even unto the present day.

People continue to build walls to keep out those who look and think differently. Some hide behind mountains or on islands, hoping to shield themselves from thoughts and ideas foreign to their way of thinking. Others are happy to entrust serious reflection and study and the making of difficult decisions to their superiors, some of whom delight in the exercise of unrighteous dominion.

But this invariably results in the infantilization of the individual, who will become disoriented when he is compelled to fend for himself or discovers information that calls into question what he was previously told was the truth. One can only imagine the angst experienced by the people of Babel when they were scattered and suddenly had to think for themselves.

Arguably, however, Babel’s greatest sin was its insistence upon ideological conformity, a transgression we commit with great frequency today. The silencing and cancelling of those who think differently is all too common in our society, and, sadly, is also prevalent in our own community.

In the most recent College Free Speech Rankings, BYU finished dead last among 55 top universities as the most difficult place for liberal-minded students to express their views.[8] While professors and administrators are generally supportive of free expression on campus, students frequently are not. As one graduate said: “My support of the LGBTQ community was … mocked by students during a religion class. I participated in a BYU College Democrats vs. BYU College Republicans debate and our side was booed loudly so many times, the moderator had to keep calming the crowd so our viewpoint could be heard.”[9]

Many have had—and continue to have—similar experiences in our church. For example, it is not uncommon for teachers to be released or reprimanded when they stray from the confines of the manual.[10]

If we do not permit discussions of these issues in our ranks, how can we hope to engage with—and attract—those not of our faith? Further, when we silence those who raise problematic doctrinal and historical questions or who advance an interpretation of scripture that differs from what is taught from the pulpit, we foolishly limit our ability to grow and learn. In the words of President Uchtdorf, we “thwart the revelations of the Spirit” and new truths are unable to pass through “the massive iron gate of what we thought we already knew.”[11]

While we are admonished to be one,[12] we are not commanded to be the same. Conformity is not a virtue. To the contrary, the Apostle Paul taught: “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.”[13]

Only a unique, unconstrained individual—someone who God knows by name—can commune with the divine.

[1] See, e.g., Old Testament Gospel Doctrine Teachers Manual, (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Salt Lake City Utah: 2001), pp. 23, 25.

[2] Craig S. Keener, et al., NKJV: Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible, (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1982), p. 29; The Five Books of Moses, trans. Robert Alter (W.W. Norton and Company, Inc.: New York, New York, 2004), p. 58.

[3] Judy Klitsner, Subversive Sequels in the Bible, (Maggid Books: New Milford, Connecticut, 2009) p. 34.

[4] Ibid, p. 39.

[5] Gen. 3:22.

[6] Gen. 1:28.

[7] Gen. 9:7

[8] “2020 College Free Speech Rankings,” RealClear Education, accessed on November 12, 2020.

[9] David Noyce, “This Week in Mormon Land: Liberals leery at BYU,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 5, 2020.

[10] Peggy Fletcher Stack, “This Mormon Sunday school teacher was dismissed for using church’s own race essay in lesson,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 10, 2015.

[11] Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Acting on the Truths of the Gospel of Jesus Christ,” Worldwide Leadership Training Conference, February 2012.

[12] D&C 38:27.

[13] Romans 12:2 (ESV).

Very well said and written plus another reference to Star Trek. Somebody raised you right!

Profoundly politically incorrect in the best sense. While disappointing that BYU students were uniformly intolerant, I’d note that your university (University of Illinois) and mine (University of Wisconsin-Madison) while building notable reputations of protest and riot have, themselves, created an intolerance of the opposite political orientation. As Aristotle sagely observed so long ago: “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” Too much of what should be healthy discourse of diverse views has deteriorated into rude name-calling which disintegrates public trust and contributes to disunity. Unity need not be conformity.

Thanks, Thorpe. I am grateful for the manner in which I was raised, and firmly believe that those parents who fail to make Star Trek a part of the education of their children should receive a visit from Social Services.

Well said, Dick. And that quote from Aristotle is one of my favorites.

It is tragically ironic that the college faculty and administrators who, over the past two decades, have sought to silence those who do not share their political views are often the same individuals who championed the First Amendment when they were leading student demonstrations in the ’60s and ’70s. Universities are supposed to be places where no ideas or opinions are off limits and everything is open to question. While no school has ever perfectly achieved that ideal, it’s said to see so many abandon it with Orwellian glee.

Great essay. I enjoyed reading it in its newest iteration. You make so many excellent points that we completely miss when we stick to the Disney version of the tower of Babel. I really enjoy how you open these stories up to new and greater meaning. It has made the scriptures so much more intriguing to me.

Thanks, S. Barnhart. I really enjoy doing this. It is especially rewarding to discover hidden meanings in stories most faiths tend to neglect or consciously ignore. And writing about them forces me to refine my analysis. One thing I discovered when I first began to practice law is that I really don’t know what I think until I write.

Very interesting piece with a lot to ponder. I enjoyed a new slant on the Tower of Babel. It makes a good deal of sense. I also know that it is very easy to call for tolerance and diverse thought when you are being shushed and ignored but it is easy to feel differently when the other side is talking. Also there is a natural tendency to resent others trying to push their slant on you. However, there is a right and wrong. There are facts. But since there is sooo much we don’t know and since often personal inspiration and interpretation are essential for growth, it is essential that we respect the opinions of others even if we don’t agree. It is a difficult balance to attain but there is also a danger of assuming a position of inability to judge between right and wrong and truth and fiction and that hampers our ability to grow as well.