The outcome of virtually all human interaction hinges on the leverage possessed by each party.

When a person, organization or country has little or no leverage, sometimes persuasion, ingenuity, good fortune, or the generosity of others, will allow them to achieve their objectives.

The Two Rules of Life, by Eric F. Facer

God made a great mistake when he limited the intelligence of man but not his stupidity.

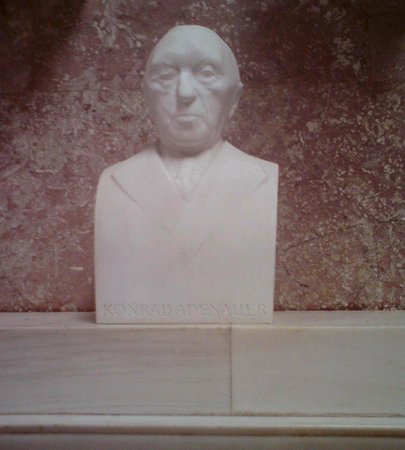

Konrad Adenauer

On February 17, 1933, Adolf Hitler disembarked from his plane at the Cologne Airport and was infuriated by what he saw. Absolutely nothing.

Three weeks earlier he had been appointed as Reich Chancellor of Germany whereupon he decided to call a general election in hopes of increasing the representation of his political party, the National Socialists, in the German parliament.[1] He had come to Cologne for a campaign event and had been assured by his advance team that the mayor, Konrad Adenauer, and a group of local dignitaries would be there to greet him, as protocol required. Because Adenauer disdained Hitler and the Nazis, he sent only a deputy to meet the Reich Chancellor. Hitler was so offended he chose to spend the night in neighboring Godesberg.[2]

In preparation for a party rally in Cologne two days later, the Nazis raised their flags on the bridges over the Rhine River. Adenauer promptly ordered them removed since they had been hoisted without his permission.[3] For Hitler, this was last straw. Storm Troopers were posted outside the mayor’s home and collection boxes were passed around, with the Brownshirts calling out, “Every penny a bullet for Adenauer.”[4] Not surprisingly, Adenauer was removed as mayor shortly after the National Socialists’ foreordained electoral victory.

Who was this impudent mayor and why did the Nazis despise him so? In my estimation, Konrad Adenauer—a man unknown to most Americans—was one of the greatest political and world leaders of the 20th century, eclipsed only by Churchill and FDR.[5] To understand and appreciate his greatness, we must begin where he began.

The Early Years

Adenauer, the third of four children, was born on January 5, 1876. His family, devout Catholics, lived in a small home in Cologne, where his father worked as a court clerk. His mother was kind and loving while his father was man of integrity and discipline. Duty, honesty and ambition, along with public service, were the principles his father lived by, and he expected nothing less from children. Both parents stressed the importance of education and taught their children to employ critical thinking when examining a proposition.[6]

Konrad was enthralled with books.[7] They opened intellectual doors and greatly augmented his understanding of the world. Not surprisingly, he excelled in school and gained admission to three prestigious universities where he studied law.[8]

After completing his education, he returned to his hometown where he worked for a local prosecutor and a civil attorney before becoming an assistant judge at the Cologne district court. He was restless, however, always seeking new opportunities to challenge his intellect and expand his horizons. When he was invited by the City Council to throw his hat in the ring for the position of Deputy Mayor, he jumped at the chance. At the young age of 30, the Council overwhelmingly approved the appointment by a vote of 35-2.[9]

His father was elated, but not satisfied, by his son’s accomplishment, saying “now the target you must set yourself is to become the Mayor of Cologne.”[10] Unfortunately, Adenauer Sr. would not live to see whether his son could accomplish that goal. Three days later he died suddenly from a stroke.

Until this time, Konrad had not exhibited any interest in politics. While he was popular, serious and ambitious, he had only a few close friends and never sought the limelight. But as a Deputy Mayor, he discovered his destiny which he zealously pursued. He outworked all of his colleagues and, just three years later, was elected to the position of First Deputy Mayor.[11]

He was now in charge of the city’s finances and personnel, and served as Acting Mayor when the Lord Mayor was away. His responsibilities grew immensely when, in August 1914, Germany declared war on Russia and France. Although each of the belligerent nations was confident the war would soon be over, Adenauer was skeptical. Anticipating shortages in the future, he immediately acquired jurisdiction over the municipal food department. He then entered into long-term contracts with area farmers and put much of Cologne’s land—a city with 750,000 residents—under the plough. Notwithstanding these measures, the city did experience some shortages as the war dragged on. But thanks to Adenauer’s foresight, it fared better than most.[12]

In the midst of the war, Adenauer’s wife, Emma died, leaving him with three young children to raise. He had always been a devoted father, spending virtually all of his free time with his kids. But his ability to care for them was greatly impaired when, a few months later, tragedy struck again: Adenauer was severely injured in an automobile accident (his driver had fallen asleep at the wheel). His nose and both cheekbones were broken, his jaw was crushed, and he lost several teeth. Even after multiple surgeries and four months in the hospital, his disfigurement was permanent and striking.[13]

When members of the Cologne City Council visited him while he convalesced in the countryside, they were concerned about Adenauer’s ability to resume his duties as First Deputy Mayor—a concern which was magnified when they saw the extent of his injuries. Upon witnessing their reaction, Adenauer wryly said, “Gentlemen, it is only outwardly that I am not quite normal.” After determining for themselves that such was the case, they offered him the position of Lord Mayor of Cologne, which he accepted with alacrity.[14] His father’s final wish had been realized. His son was now the youngest Lord Mayor in all of Prussia.[15]

The Weimar Republic

You would think the stress of the Lord Mayor’s job would have abated somewhat when the war ended in November 1918. But you would be mistaken.

A few days before the armistice was signed, Cologne was besieged by hundreds of mutinous sailors who, inspired by the Russian Revolution of October 1917, were proclaiming a Rhineland communist republic outside the Cologne Cathedral. Rioting and looting soon followed, but the authorities turned a deaf ear to Adenauer’s for request assistance in suppressing the violence.

Left with no alternative, he spoke cautiously and respectfully to the leaders of the revolutionaries, who agreed to cooperate. Order was restored by a volunteer civil guard, but the peace did not last.[16] A new crisis was on the horizon: hundreds of thousands of armed and hungry German soldiers, returning from the front, were about to pass through Cologne on their way home.

Once again, Adenauer was left to his own devices. And once again, he responded brilliantly. Field kitchens were quickly assembled for the troops, and each soldier was required to surrender his weapons as a prerequisite to receiving his discharge papers. To finance this effort, he auctioned off all army property at his disposal.[17]

After the post-war chaos abated, Adenauer, having become smitten with Auguste (“Gussie”) Zinnser—a woman almost twenty years his junior—found time to remarry.[18] Germany, too, made a fresh start. It adopted a new constitution, establishing the country’s first democratic regime: the Weimar Republic.

The nation’s Reichstag (i.e., parliament), however, never attained the cohesion required to govern effectively. Over the next seven years, twelve different governments would rise and fall.[19]

The resulting political and economic instability triggered runaway inflation, almost destroying Germany’s democratic project. Inevitably, these developments made Adenauer’s job considerably more difficult. Nevertheless, he succeeded in modernizing the city and expanding its industrial base, the crown jewel of which was a new Ford Motor Company manufacturing facility.[20]

The stock market crash of 1929, however, irreparably shredded the political fabric of the nation and its economy, setting the stage for the rise of National Socialism. As noted, Adenauer’s fourteen-years as Lord Mayor came to an abrupt halt in 1933 when he refused to endorse Germany’s new chancellor, Adolph Hitler.

National Socialism

To avoid arrest, torture and perhaps execution, Adenauer sought refuge at the Maria Laach monastery where the abbot was an old school friend; meanwhile, Gussie and the couple’s four young children remained in Cologne.[21] While at the monastery, he spent much of his studying two Papal Encyclicals published by Pope Leo XIII in 1891, which applied Catholic teachings to the social and political sphere.

The doctrines he encountered were harmonious with his own political convictions. The encyclicals rejected socialism since it sought to abolish private property, thereby discouraging workers from striving to improve their conditions. Free markets and competition, tempered with Christian charity and humility, were the best way to ameliorate class struggles.[22]

His stay at the monastery came to an end after Nazi officials pressured the abbot to evict him. For the next ten years he was constantly on the run, often staying at one location for no more than a day or two.[23]

Adenauer and his family kept a low profile throughout the war. Nevertheless, he was imprisoned two times by the Nazis. His second incarceration occurred in 1944 when was he jailed on suspicion of being a co-conspirator (he wasn’t) of “Operation Valkyrie,” an unsuccessful plot to assassinate Hitler.[24]

The prison where he was housed was filled with the screams of other inmates being tortured. And the window of his cell gave him an obscured view of the daily executions. Ultimately his son, Max, who was serving in the German army, secured his release.[25]

As the war drew to a close, Adenauer began to contemplate a return to a public life and whether he might find a leadership role in his country, one staggering under impact of total military defeat, economic collapse, and moral devastation.

A New Beginning

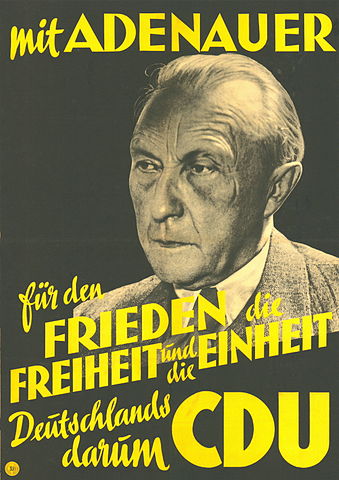

Towards the end of 1945, he attended a meeting in Cologne convened to create a new political party, one with a foundation in Christianity, both Catholic and Protestant. This informal group settled on a name—the Christian Democratic Union (the “CDU”)—and scheduled another gathering for the following month.[26] During the interim, Adenauer, a man of extraordinary vision, fine-tuned his political philosophy, one grounded in democracy, social conservatism and—most importantly and most radically—and a belief that full integration with Europe and strong ties with the United States were Germany’s best hope for the future.[27]

When he presented his plan at the CDU’s next meeting, he did so in a subdued, self-assured manner, speaking in a conciliatory tone—the antithesis of Adolph Hitler’s bombastic and confrontational style. Adenauer, rarely raised his voice, never interrupted others, and chose his words carefully. Dean Acheson—a brilliant U.S. diplomat who played a key role in rebuilding Europe after the war—after meeting Adenauer for the first time, said he was “the human embodiment of the doctrine of the conservation of energy.” He was inscrutable, speaking slowly with a keen sense of irony and always in control of his emotions.[28] His demeanor and forward-thinking policies, combined with his resolute opposition to the National Socialists during the Hitler era, made him the obvious choice as party leader, a stewardship that lasted 15 years.

But in the midst of his nascent efforts to create a new Germany, personal tragedy struck again.

In 1944, his second wife, Gussie, was arrested by the Gestapo, who threatened to incarcerate her teenage daughters if she did not divulge the whereabouts of her husband who was wanted on suspicion of complicity in the failed attempt to assassinate Hitler. She ultimately relented, but was so mortified by her supposed treachery she attempted suicide—twice—but failed each time. Having never fully recovered from this trauma, she died four years later at the age of 52. Adenauer, now in his 73rd year, was understandably distraught; nevertheless, he somehow mustered the strength to press on.[29]

Though Adenauer was now the leader of a major political party, his country was no longer a sovereign nation. The principal countries allied against Germany—the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and France—had divided the country into four administrative zones. The U.S.S.R. controlled the Eastern quarter while the other allies were in charge of those in the east (Great Britain), the southwest (France) and the south (the U.S.).

Once order had been restored and a competent government was operational, the allies would withdraw their occupying forces and Germany would regain its independence.[30] In the three regions occupied by the Western allies, this joint initiative began with economic assistance and the restoration of electoral democracy at the local level. As the process unfolded over the next four years, it became apparent that Stalin had different plans for the eastern sector, calling into question the full reunification of pre-war Germany.[31]

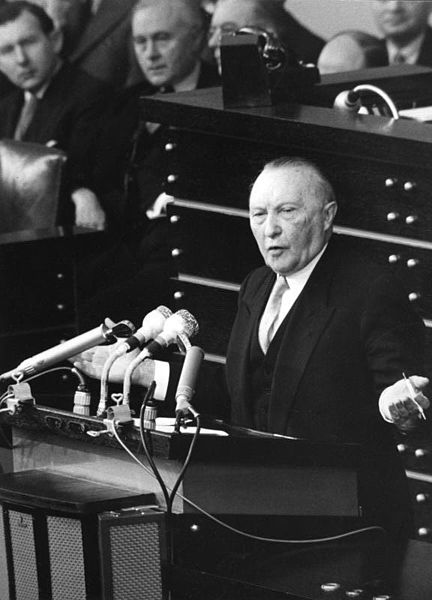

Reunification suffered a major setback when Stalin, in 1948, blockaded the City of Berlin. The following year, the allies responded by backing the creation of the Federal Republic of Germany, consisting of the three Western zones. (The German Democratic Republic—more commonly known as East Germany—was constituted several months later.) Simultaneously, West Germany adopted a new constitution (the “Basic Law”) and a national election was held. Adenauer’s party won a majority of the seats in the new parliament (the Bundestag) and a few weeks later he was elected chancellor—by one vote, presumably his own.[32]

A new constitution and parliament were not tantamount to the restoration of full sovereignty. To the contrary, the Western allies, under the auspices of the Occupation Statute, retained control over foreign affairs, the expenditure of funds, and all matters concerning German rearmament.

Chancellor Adenauer, in a brief acceptance speech before the Three High Commissioners from the U.S., Britain and France, accepted the limitations under which his government was required to operate. But instead of appealing to the victors for generosity, he enticed them with his vision of a European Federation designed to overcome the aggressive nationalism often exhibited by Germany, France and England over the past 200 years. “If we now turn back to the sources of European civilization, born of Christianity, then we cannot fail to succeed in restoring the unity of European life in all fields of endeavor,” he declared. [33]

This was a masterstroke, one warmly received and endorsed by the Americans. But Adenauer’s political opponents in the Bundestag—principally Kurt Schumacher, leader of the German Social Democratic Party—argued that German policy was the exclusive province of Germans and should “not [be] determined by foreign will.”[34] Adenauer knew Germany must temporarily accept inequality among the family nations if it were to regain its status as an equal, so he was perturbed by the obstinance of the opposition. At one point in the debate, he became so frustrated with Schumacher he, uncharacteristically shouted, “Who do you think lost the war?!?”[35]

Another reason why Adenauer’s opponents disapproved of European integration was the seemingly insurmountable hurdle it created for full German reunification. Stalin also understood this and, in March 1952, decided to test Adenauer’s resolve by proposing a reunited Germany with its own armed forces, full control over its economy, and the withdrawal of all occupying forces. But there was a catch: a united Germany must forever remain politically neutral.

Schumacher, not surprisingly, publicly urged Adenauer to seize this opportunity to negotiate, arguing that the Bundestag should postpone further European integration until this opportunity had been explored. Seemingly painted into corner, Adenauer adroitly said he would consider pursuing negotiations—provided free and open elections had been accepted by all parties, including the Allies—and were built into a new constitution. America, Great Britain and France understood his gambit and embraced it completely. Predictably, Stalin withdrew his offer since his goal was not a democratic Germany, but one he could control.

The growing threat posed by the Soviet Union prompted the allies to establish what became the centerpiece of American policy in Europe: a mutual defense agreement known as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (“NATO”). Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander of NATO, believed 30 divisions (450,000 soldiers) were needed to protect Europe. And to achieve those numbers, Germany must be allowed to rearm. Adenauer, who coveted membership in NATO,[36] seized this opportunity to contribute.

With some reluctance Britain consented to this proposal, but France refused. Having been invaded three times across the Rhine between 1870 and 1940, its reluctance to allow Germans to take up arms again was understandable.[37] But when Eisenhower won the presidency in November 1952, he and Prime Minister Anthony Eden persuaded France to agree to Germany joining NATO.

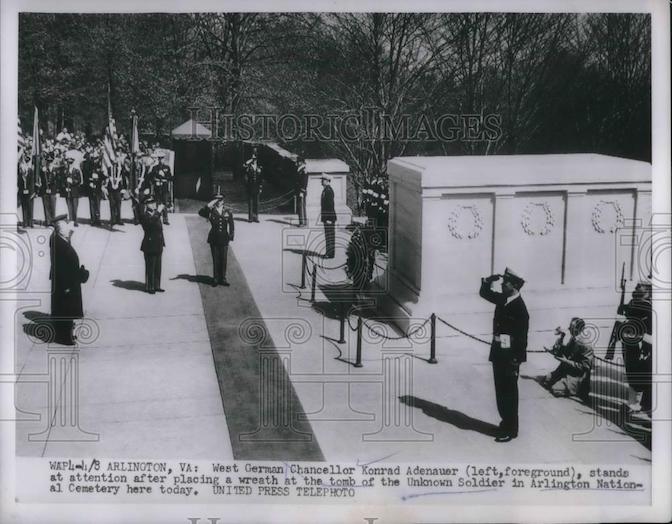

In a mere eight years, Germany had recovered virtuality all of its sovereignty. The culmination of Adenauer’s efforts coincided with a trip he made to the United States in the spring of 1953. While there, he, accompanied by several dignitaries, visited the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery.

As he approached the Tomb, a 21-gun salute sounded in scene Adenauer movingly recorded in his memoirs:[38]

An American band played the German national anthem. I saw how tears were running down the face of one of my companions, and I, too, was deeply moved. It had been a long hard road from the total catastrophe of 1945 to this moment of the year 1953, when the German national anthem was heard in the national cemetery of the United States.

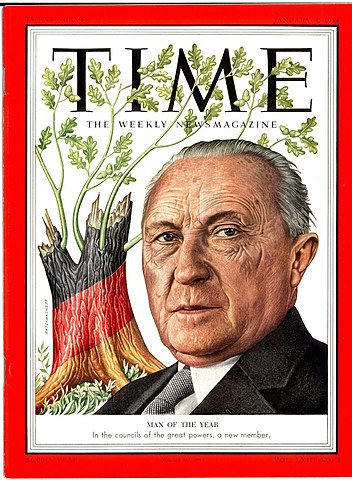

Fittingly, on January 4, 1954, he was named Time Magazine’s “Man of the Year.”

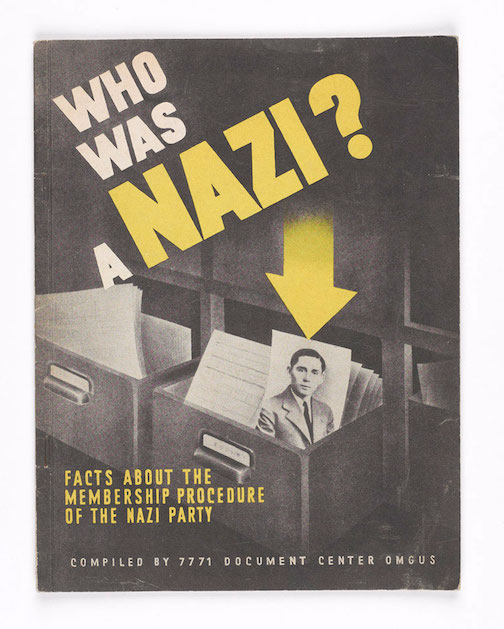

Moral Reckoning: Denazification and Restitution

The economy and infrastructure of Germany were not the only things laid waste by the war; the psyche of the German people was also in tatters. The enormity of the crimes committed by the Nazis were something the survivors could not comprehend or, in many instances, refused to believe.[39] A moral reckoning was most certainly necessary, but there was the question of when that should occur.

The allies believed it should begin immediately. They wanted all Nazis removed from positions of power and influence in politics, education, business, the media, and the law. This policy, however, was doomed to fail and Adenauer knew it.[40]

Over six million Germans had been members of the Nazi party. To exclude from society even a fraction of that number would thwart the nation’s ability to recover from the war. Many National Socialists possessed skills and expertise that were essential to Germany’s rebirth.[41] Further, ostracizing them would sow the seeds of rebellion, possibly triggering a civil war from which the country would never recover. The exigencies of the Cold War also argued in favor of amnesty, except in the most egregious cases.[42]

Like the ancient Athenians who wrestled with the question of whether to punish those who conspired with the Thirty Tyrants or grant them amnesty, Adenauer chose to look to the future. At the same time, he said “it is absolutely essential to draw the necessary lessons of the past in the face of all those who challenge the existence of our state.”[43] Thus, in 1952 he banned the Socialist Reich Party, which had attracted ex-Nazis and was gaining a following.[44]

Adenauer’s approach was not without its detractors and is being debated by historians to this day.[45] One of his most controversial appointments was his choice of Hans Globke, one of the authors of the 1935 Nuremberg Race Laws, to be his Chief of Staff. Egon Bahr, a prominent politician, reacted with horror not only to Globke’s appointment, but also to the reinstatement of many other senior Nazis in the judiciary, the medical profession and universities. Adenauer’s response was direct and to the point: “One does not throw out dirty water while one does not have clean.”[46]

To the surprise of many, Bahr later revised views of Adenauer:

At a distance of decades my judgement has softened under the realization that old Adenauer had a huge task to perform. He was faced with a state that had six million Nazi party members, and expellees from the East among whom the proportion of Nazis was no smaller. He had to ensure that this explosive mixture did not detonate. That is statesmanship.

Adenauer’s leniency towards former Nazis did not cause him to lose sight of the unspeakable harm his country had inflicted upon the Jewish people and Germany’s moral obligation to make restitution. When Israel, in 1951, asked the Soviet Union and the four occupying powers for reparations in the amount of $1.5 billion to the survivors of the Holocaust and their heirs, East Germany and Stalin never responded. But Adenauer’s government openly acknowledged and accepted responsibility for the crimes committed by the Third Reich and pledged to make recompense.[47]

A reparations law was passed two years later, and aid to Israel was prompt and substantial. According to one historian: “The German deliveries to Israel of ships, machine tools, trains, autos, medical equipment, and more amounted to between 10 and 15 percent of annual Israeli imports.”[48] Payments totaling billions of dollars to both the descendants and survivors of Nazi persecution dollars have been made since the 1950s and continue through the present day.

Germany established full diplomatic relations with Israel in 1965, two years after Adenauer retired as Chancellor. The following year Adenauer, travelled to Israel as a private citizen. Upon his arrival he declared, “this is one of the most solemn and beautiful moments of my life … never did I think, when I became Chancellor, that I would one day be invited to visit Israel.”

But his visit was not without controversy and confrontation. During a dinner held in Adenauer’s honor, Israeli Prime Minister, Levi Eshkol lectured him publicly, saying “We have not forgotten and we shall never forget the terrible Holocaust in which we lost 6,000,000 of our people.” He went on to say that Germany’s reparations payments were “only symbolic” and could never erase the tragedy which occurred.” Ever the diplomat and gentleman, Adenauer quietly responded: “I know how difficult it is for the Jewish people to forget the past but should you fail to recognize our good will, nothing good can come of it.”[49]

In 1999, Konrad Adenauer—statesman and visionary, husband and father, servant and saint, and the greatest national leader in German history—was enshrined in Walhalla, the Hall of Heroes. May God bless his soul, grant him peace, and send us more men like Konrad Adenauer.

[1] Henry Kissinger, Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy, (New York, New York: Penguin Press, 2022), pp. 6-7.

[2] Charles Williams, Adenauer: The Father of the New Germany, (New York, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000), p. 208.

[3] Ibid., p. 209

[4] Edyth Cudlipp, World Leaders Past and Present: Adenauer, (London, England: Burke Publishing Co. Ltd., 1988), pp. 47-49; see also The Father, p. 210.

[5] Churchill described called Adenauer “the wisest German statesman since the days of Bismarck.” Hansard, Foreign Affairs, House of Commons Debate, May 11, 1953, vol. 515, columns 889-890.

[6] The Father, pp. 3-7.

[7] World Leaders, p. 16.

[8] Ibid, pp. 25-28.

[9] Ibid, pp. 48-49.

[10] The Father, p. 49.

[11] Ibid, p. 55.

[12] World Leaders, p. 24; The Father, pp. 63-64.

[13] The Father, pp. 70-71.

[14] Ibid, p. 72.

[15] Ian Kershaw, Personality and Power: Builders and Destroyers of Modern Europe, (New York, New York: Penguin Press, 2022), p. 206.

[16] World Leaders, pp. 29-30.

[17] The Father, 98.

[18] Ibid, pp. 115-17.

[19] World Leaders, pp. 40-42.

[20] Personality and Power, p. 206; Scott Nehmer, Ford, General Motors and the Nazis: Marxist Myths About Production, Patriotism, and Philosophies,(Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, LLC, 2013), pp. 38-39.

[21] Ibid, p. 218. Adenauer’s three children from his first marriage were now adults and able to fend for themselves.

[22] The Father, pp. 221-d22; Leadership, p. 7.

[23] The Father, p. 237.

[24] Adenauer declined to participate in the plot for two reasons: (1) he doubted it would succeed, and (2) failure would mean not only the death of the conspirators but their family members as well.

[25] The Father, pp. 283-285.

[26] Fritz Stern, The Five Germanys I Have Known, (New York, New York: Farrar: Straus and Giroux, 2006), pp. 181-182.

[27] Leadership, pp. 8-9.

[28] Dean Acheson, Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department, (New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1969), p. 341.

[29] The Father, pp. 282-283, 321-322.

[30] Leadership, p 4.

[31] Ibid, p. 11.

[32] Personality and Power, p. 212.

[33] United States Department of State, Germany 1947-1949: The Story in Documents, (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1950), p. 321).

[34] Thomas Hörber, The Foundations of Europe: European Integration Ideas in France, Germany and Britain in the 1950s, (Heidelberg, Germany: Vs Verlag fur Sozialwissenschaften, 2006), p. 141.

[35] Ronald J. Granieri, The Ambivalent Alliance: Konrad Adenauer, the CDU/CSU, and the West, 1949-1966, (New York, New York: Berghahn Books, 2003), p. 34.

[36] John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History, (New York, New York: The Penguin Press, 2005), p. 135.

[37] Personality and Power, p. 213.

[38] Leadership, p. 22.

[39] Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945, (New York, New York: The Penguin Press, 2005), p. 57.

[40] Personality and Power, p. 225.

[41] Postwar, pp. 57-58.

[42] Peter Watson, The German Genius: Europe’s Third Renaissance, the Second Scientific Revolution, and the Twentieth Century, (New York, New York: HarperCollins, 2010), p. 759.

[43] Aftermath, p. 317.

[44] Personality and Power, p. 225.

[45] See Charles R. Browning, “Adenauer’s Bargain,” The New York Review of Books, December 22, 2022. pp. 69-70.

[46] Harald Jähner, Aftermath: Life in the Fallout of the Third Reich: 1945-1955, (New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022), pp. 317-318.

[47] Leadership, p. 24.

[48] Jeffery Herf, Divided Memory: The Nazi Past in the Two Germanys, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997) p. 288.

[49] Leadership, p. 25-26.

One thing I wonder about a lot is how I would personally have acted if I were living in Germany during the Nazi era or in one of the countries occupied by the Nazis. I would love to think that I would have joined the active resistance, served as a spy, or actively worked to protect the Jews and other targets of Nazi genocide.

But the reality might have been different, realistically would probably have been different. Having come of age as a white boy in segregation-era Mississippi, I know that the pressure to conform to majority sentiments of hatred is enormous even in the relative safety of late 20th century America. Of course, the physical dangers confronting those who opposed the Nazis were enormous and were not limited to the opponents themselves, but extended to their families as well. And circumstances were such that among those brave enough to actively oppose the Nazis, most were in a position where they realistically could do nothing — they had no way to join the resistance, no contacts with any spy networks, and no contacts with Jews or other Nazi victims.

So I mean no criticism of Adenauer at all when I say that he chose from 1934 to the end of the War to focus on self-preservation of himself and his family. He did not join any resistance groups or take part in any organized opposition to the Nazis as far as we know.* Instead, he focused on having his government pension restored and being compensated for the Nazis’ confiscation of his home (at least that’s what Wikipedia says, I haven’t read Adenauer’s biography), even to the extent of writing a ten-page letter in 1934 to Herman Goring outlining the ways in which he had been helpful to the Nazis as mayor of Cologne. Again, I am not being critical of Adenauer for these choices. These were horrendously difficult days for opponents of the Nazis, and the moral and practical choices they faced were more difficult than any such decisions that I (or most any living American) have ever faced.

Of course, this fascinating essay on Adenauer is intended to be read in conjunction with the preceding essay on Sophie and Hans Scholl, who made very different choices than Adenauer during the Nazi era, choosing to die in a blaze of idealistic glory publicly fighting against the Nazis.

While the choices of the Scholl siblings were inspiring and unbelievably brave, they accomplished little. Certainly, the world would have been a worse place if Adenauer, who played such a critical role in restoring liberal democracy to post-war Germany, had made a similar moral choice during the Nazi Era and died as a result.

* One question for you, Eric. Footnote 24 arguably implies that Adenauer was offered the choice of participating in Operation Valkyrie and declined. Is that the case? If so, I would love to learn more about what Adenauer said about his decision not to participate.

The story (and Doug’s comment) are outstanding. Thank you for sharing the story of Adenauer, a man whose name I have only heard but didn’t really know much about. So many lives of goodness and bravery eventually dim and but I am thankful for them.

Doug, I think your assessment of the dilemma confronting those Germans who wished to stop Hitler but knew risks of doing so were enormous while the chance of success was remote, is accurate. When I judge the actions of individuals in circumstances such as these, the older I get the more inclined I am to give them benefit of the doubt. This is one of the reasons I chose not to judge Robert E. Lee too harshly. But for the grace of God . . . as the saying goes.

Erik Larson wrote a book around ten years ago called “In the Garden of the Beasts,” which is about William Dodd’s experiences in Berlin during the 1930s as the United States’ ambassador to Germany. One of the things that struck me about his experiences were number of intellectuals and professionals he met who loathed Hitler (no surprise there) but did little to stop him because they thought him a tramp surrounded by goons who would eventually self-destruct. By the time they realized they were wrong—an epiphany likely experienced after witnessing Kristallnacht—it was too late. As one German said after that dark night, “From whom could decent Germans now expect protection if these horrible excesses were followed by others? … the cowed middle class stared at the Nazi monster like a rabbit at a snake.”

As to Adenauer and Operation Valkyrie (also known as the “Stauffenberg plot”), he was first invited to participate in this undertaking in the fall of 1942 (it was expected to occur much sooner than July 1944, but repeatedly was called off). Dr. Karl Goerdeler, the former mayor of Leipzig, and two of his civilian friends, along with a group of Army generals, were the “masterminds” behind the plan to assassinate Hitler.

Adenauer was approached by this group because he was their first choice for the office of Chancellor once Hitler was out of the way. But Adenauer refused to even see Goerdeler. He had known him when they were colleagues on the Prussian Staatstrat—the State Council, which was the upper chamber of the bicameral legislature of Prussia—and he was not impressed.

Adenauer also knew that Goerdeler couldn’t keep his mouth shut. He bragged about his connections with the military and also let it be known that he was in touch with British and French agents who were willing to lend support. Frankly, this guy reminds me of Squire Trelawney in Stevenson’s “Treasure Island” who, even after he was told by all concerned that secrecy was of the utmost importance, bragged to anyone who would listen that he was looking for a ship and crew to help him find buried treasure in the Caribbean. His loquacity was rewarded with Long John Silver.

Adenauer also believed that the generals in question would ultimately follow orders and couldn’t be relied on. As it turns out, Adenauer’s assessment of Goerdeler was spot on.

Even though, miraculously, the Gestapo and the SS never got wind of the July 1944 plot, Adenauer was still implicated since his name was found in the correspondence of the conspirators. Hence his interrogation and probable execution but for the intervention of his son.

Adenauer, like everyone, had his flaws. He was Machiavellian at times and did not suffer fools gladly, but in all my reading and research, I found no evidence of cowardice (and I know you were not implying that he was a coward).

Finally, I want to echo Jeff’s praise about your comment. You frequently see things in these historical episodes that I miss, prompting me at times to rethink my assumptions. And I appreciate it.

Eric, that episode is fascinating. We rarely learn the details of people who face such difficult moral dilemmas. Adenauer’s choice seems right to me, and not cowardly in any way.

Eric

What an amazing piece of scholarship. I was, of course, aware of Adenauer but only in a surface way. You have presented an insightful look at the juggle between the ideal and the practical, compfromise and principle, and the painful process of healing and changing all of which to some degree or another are part of the challenges of life in am imperfect world. I salute you and also found the comments very beneficial. I’m going to send you a copy of an excellent book Mindy have be for my birthday, DAUGHTERS OF YALTA

Thank you so much, Karen, for your kind words, additional insights, and thoughtfulness. I usually tell people not to give me works of history since, in all probability, I either own it or am aware of it and decided I didn’t want to read it. But I am unfamiliar with the “Daughters’ of Yalta” and look forward to reading it.