Healing the blind was one of the most frequent miracles performed by Christ during his earthly ministry. But one of those divine interventions sets itself apart from the rest: The Healing of the Blind Man at Bethsaida, which can only be found in the Gospel of St. Mark.

Bethsaida was a town located on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee. When Jesus arrived there, the locals brought to him a blind man and asked the Savior to heal his affliction. Christ first led him out of the village and then put saliva on his eyes after which he laid his hands on him. Then he asked, “Do you see anything?” The man replied, “I see people, but they look like trees, walking.” Then Jesus laid his hands on his eyes again. This time when the man opened his eyes, he saw everything clearly.

This miracle is unique because it happens in two stages. The first effort at curing the man’s vision was only partially successful, requiring a second go at it. Neither Matthew nor Luke included this miracle in their gospels, perhaps because they were concerned it might imply that Jesus’ powers were somehow deficient. Or they may have been bothered by the magical gestures accompanying its performance.[1]

One explanation often proffered for the failure of the first attempt or the use of saliva in the process is that the faith of the blind man was weak. But there is nothing in the story to support that conclusion. His faith was never called into question, either at the beginning of the parable or by the Savior after the first attempt failed. So what’s going on here?

We often fail to divine the meaning of the miracles because we see them simply as a manifestation of the Savior’s divine authority. But the Evangelists saw in them much more. They believed the point of the miracles was not medical but spiritual and theological. And they frequently arranged the miracles in such a way as to lead progressively to the spiritual truth they were trying to communicate. Thus, the answer to the riddle of The Healing of the Blind Man of Bethsaida can be found in what comes next.

Immediately afterwards, beginning with verse 27, we find Christ retreating to Caesarea with his disciples where he puts to them a question: “Who do people say that I am?” Following their responses (e.g., John the Baptist), he makes a second inquiry: “But who do you say that I am?” Peter experiences an epiphany, causing him to boldly declare that Jesus is the Messiah.

Christ then tries to build on that understanding by explaining what lay in store for him as their Savior—persecution, death and resurrection—but Peter will have none of it, reprimanding Jesus, the Messiah, for even thinking such things. The response he received, however, must have come as a shock:

But when He had turned around and looked at His disciples, He rebuked Peter, saying, ‘Get behind Me, Satan [Accuser]! For you are not mindful of the things of God, but the things of men.’

Mark 8:33 (NKJV)

There are two profound lessons embedded in these passages.

First, the two-stage healing of the blind man of Bethsaida, positioned immediately before the dialogue at Caesarea, teaches that the revelatory process is not as simple as depicted in the hymn, “Amazing Grace”: “I was blind, but now I see.”[2] Rather, it occurs incrementally over time. Peter’s spiritual vision only improved gradually, requiring constant refinement throughout his life. So, too, with each of us.

Second, Christ’s reprimand of Peter is noteworthy because of both its harshness and its failure to enlighten. Culturally, a forceful censure such as this was a common feature of rabbi-pupil interactions. Indeed, in the Qumran literature, chastisement by God was viewed as a prerequisite to understanding; it was actually something for which to be grateful.[3] Far better to be singled out for correction than to be ignored.

But why didn’t the Savior explain to Peter the nature of his error? Simply stated, that is not how Christ operates. He didn’t explain the meaning of his parables,[4] the truths embodied in the miracles he performed, or the theology of the Sermon on the Mount. His listeners and disciples were expected to prayerfully study his words, decipher their meaning, and then put them into practice. Only then would they discover their full import.

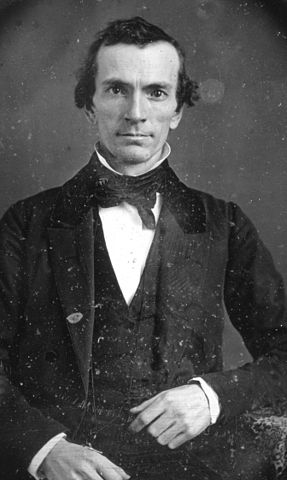

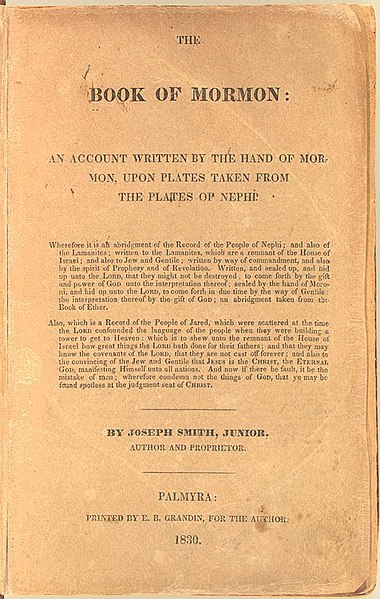

Oliver Cowdery learned this lesson when he sought to assist Joseph Smith with the translation of the Book of Mormon. When he failed at this endeavor, the Savior, by way of explanation, did nothing more than say, “… you took no thought save it was to ask me.”[5]

Daguerreotype of Oliver Cowdery taken in the 1840s, by James Presley Ball

Cover page of The Book of Mormon from an original 1830 edition

His request was not preceded by the requisite study and spiritual reflection. Had he done this, he was told, “…you could have translated…”[6] But he wasn’t told what to study or what other steps he should have taken to prepare himself before going to the Lord with his petition. This he was expected to pursue on his own, with the Lord providing guidance as he, Oliver, took the first step forward. But he never did.

Something similar occurred, I believe, when David O. McKay failed in his efforts to convince the Lord to lift the ban on black members receiving the Priesthood and the blessings of the temple. He served as church president from 1951 to early 1970, a period of considerable racial unrest in the United States. In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court required all public schools to integrate, something McKay and most members of the Quorum of the Twelve opposed, with the notable exception of President Hugh B. Brown.

McKay and the church leadership felt the same way about the civil rights legislation introduced and enacted in the 1960s. In the words of one of his biographers, “he maintained a harsh attitude towards civil rights until his death.”[7]

At the same time, President McKay began to ponder the origins and history of the Priesthood Ban. The issue became more pressing as the citizens of certain African nations—most notably, Nigeria—entreated the church to send missionaries to teach them the gospel. But without a permanent indigenous priesthood presence, the church would not be sustainable.

When he raised the subject of ending the ban with his colleagues, they showed little interest and some were openly hostile to the idea—especially his two immediate successors, Joseph Fielding Smith and Harold B. Lee. Indeed, Lee’s daughter confided to a friend, “My daddy said that as long as he’s alive, they’ll never have the priesthood.”[8]

McKay did try to reclassify the ban as a “policy” as opposed to a “doctrine,” though this was largely semantics since both he and his colleagues agreed that, “Until a revelation upon this subject is actually received no change can be made.”[9] On more than one occasion he petitioned the Lord for permission to lift the ban, but permission was never granted.

Towards the end of his life, he broached this subject with God one last time, but was stunned by the abrupt response he received. Immediately thereafter, he shared his experience with some individuals in the Church Building Department with whom he was well acquainted:

I remember one day that President McKay came into the office. We could see that he was very much distressed. He said, ‘I’ve had it! I’m not going to do it again!’ Somebody said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘Well, I’m badgered constantly about giving the priesthood to the Negro. I’ve inquired of the Lord repeatedly. The last time I did it was late last night. I was told, with no discussion, not to bring the subject up with the Lord again; that the time will come but that it will not be my time, and to leave the subject alone.’

Gregory A. Prince & Wm. Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, (Salt Lake City Utah: Univ. of Utah Press, 2005), p. 104.

President McKay appears to have made the same mistake as Oliver Cowdery. He thought all he had to do was ask since what he was seeking was, on its face, undeniably righteous. But this was not a revelation he and his colleagues were prepared to receive.

They did not comprehend the second great commandment in its fullness as given expression in a book of scripture written especially for their benefit: “…black and white, bond and free, male and female; and he remembereth the heathen; and all are alike unto God.”[10] Given McKay’s opposition to equal rights for members of the black race and the extreme reluctance on the part of so many apostles to lift the ban, is it any wonder the Lord denied his request? If they were not prepared to treat blacks as equals for all purposes, lifting the ban would have been an abject failure.

Their threshold error was believing that “only the Lord can change it.” With these words, they relegated themselves to the role of passive observers, believing they were powerless to alter the course of events. But they were not alone. People like me, for example, who made no effort to befriend black classmates in high school during the racial unrest that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King in the late 1960s, will be asked why our courage faltered at a critical time in the history of our country and our church.

In reality, the Lord is powerless to deny us a revelation we are worthy to receive. He is bound by a law, irrevocably decreed in heaven, to bestow upon us the blessing of all knowledge and revelation we have demonstrated the capacity to understand. To his credit, David O. McKay, in the face of considerable opposition from his colleagues, did soften “the Priesthood ban around the edges”[11] and gave the matter a higher priority than ever before, paving the way for Spencer W. Kimball to obtain the long sought after revelation eight years after McKay’s death.

When Peter failed to grasp the nature of the Lord’s messianic mission, Jesus was compelled to stop, turn around, and point out his error. His pace was slowed because of Peter’s spiritual blindness, thereby impairing Jesus’ ability to accomplish all required of him before his time on earth came to an end. I shudder to think how many times he has turned around only to discover I have strayed from the course he has plotted, and I can only hope he will be as patient with me as he was with Peter.

[1] Jeffrey John, The Meaning in the Miracles, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2004), p. 130.

[2] The Meaning in the Miracles, p. 130.

[3] Zondervan Illustrated Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament: Volume 1, Gen. Ed. John H. Walton (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2009), p. 256.

[4] As I explained here and according to most biblical scholars, the one or two places where Christ appears to explain his parables to his disciples in private are considered to be later additions made by scribes in the second or third centuries to advance a particular political or doctrinal argument.

[5] D&C 9:7.

[6] D&C 9:10.

[7] Gregory A. Prince & Wm. Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, (Salt Lake City Utah: Univ. of Utah Press, 2005), p. 60.

[8] Ibid, p. 64.

[9] Ibid, p. 89.

[10] 2 Nephi 26:33.

[11] Rise of Modern Mormonism, p. 105.

Great insights. Thanks for sharing.

I’ve always told B that the key to being a good parent is to “go at kid pace.” Otherwise they don’t learn anything and as a parent you only get frustrated. So, you give yourself an extra 15 minutes to get into the car, you expect a simple errand to take twice as long as it should, you cut the number of activities in half on vacation, you let dinner clean up take an hour when you could have done it yourself in half the time…I love how you’ve applied this concept to gaining spiritual knowledge. And how its our own stubbornness and blindness that keeps us from receiving greater light. I really like this quote, “In reality, the Lord is powerless to deny us a revelation we are worthy to receive” – I can only hope I am worthy to receive more that the Lord has to offer. Like McKay, however, we are bound not only by our own personal limitations but by the biases and ignorance of those around us to an extent. This reminds me of how my teenagers are anxious to go for a long, technical hike but are still stuck on the 2 mile nature loop because other members of the family still have short toddler legs. I guess that sounds sort of arrogant, but, to be sure, I wouldn’t ever presume to know if I’m the teenager or the toddler when it comes to my spiritual legs.

This is a great accompaniment to the previous post about smallpox. Similar principles apply. We are all works in progress and understanding is a constant effort to refine our ideas thoughts, and actions to perceive what is possible. Action on our part whether metal or physical, is crucial and doesn’t always result it what we might expect. I guess it is true for body and soul. Sometimes I ponder as to our relationship to Christ and think we are all parts of Christ, separated from him when we came to this mortal state and now just trying to refine ourselves and learn how to make ourselves circle back to where we belong and desire to end up, one with the Savior. In mortality we “see through a glass darkly” (remember that discussion) and try to clarify what is real and what is possible and how to achieve the superior desired goal.

I did not know Pres. McKay was so specifically hostile toward civil rights nor that most members of the 12 at that time were also hostile. I know that he and Elder Benson falsely believed (and said as much in Conference talks) that civil rights leaders were being used by Communists and other outside agitators.

In this time when so many Americans right now being misled about election results or whatever, it is disappointing that church leaders back then were similarly duped and ended up on the wrong side. As I’ve said before, it is disappointing to me that, at least in my opinion, the church has not fully made good on this damaging legacy towards blacks.

Bill, thank you for kind words.

S. Barnhart, you are correct—we are in fact bound by both our limitations and those around us. But those around President McKay were not toddlers, but adults, and the job of a leader is, through persuasion, long suffering and love unfeigned, to get those who walk with him to pick up the pace.

As I noted in my essay, when it came to civil rights the fault didn’t lie solely with McKay and the Quorum of the Twelve. Too many members also opposed the legislation or were indifferent about its passage. This was a communal sin.

Spencer W. Kimball’s motto, when he became church president, was “Lengthen Your Stride.” When it came to ending the Priesthood Ban, he understood the importance of keeping pace with Christ.

Jeff, if anything, I understated the hostility of the Quorum of the Twelve towards the civil rights movement. One member of the quorum, Delbert L. Stapley sent a letter to George Romney, who was then Governor of Michigan (1963-1969), advising him to withdraw his support for the Civil Rights Act. Stapley’s letter even contained a thinly veiled threat that if Romney did not heed his counsel, the Lord might choose to cut his life short.

Joseph Fielding Smith was not only opposed to the civil rights movement but also to lifting the Priesthood Ban. He was so displeased with Hugh B. Brown, one of McKay’s counselors, for taking the opposite stance on these issues that many believe this was the reason Smith chose not to include Brown in his presidency, the first time that had ever occurred in the history of the church. (Sadly, it was replicated when Russell M. Nelson chose not to invite President Uchtdorf to become one of his counselors.) I could go on, but you get the picture.

And no one should believe that the lifting of the ban in 1978 was a foregone conclusion. Spencer W. Kimball struggled mightily to bring several general authorities along. The process was so difficult that he doubted whether he could pull it off. He told Jack Carlson, one of his trusted advisors: “I don’t know that I should be the one doing this, but if I don’t, my successor [Ezra Taft Benson] won’t.” As the British would say, it was a damn close run thing.

I wholeheartedly agree with your views regarding the church’s failure to fully make “good on this damaging legacy towards blacks.” For a church that bears the name of Christ to be the last major Christian denomination to treat blacks as equals is a … well, I can’t think of a word right now that my website software wouldn’t censor.

Karen, I agree that we “are all works in progress,” though this does not excuse individuals or institutions when they engage in behavior—in this case, racial discrimination—that is not in harmony with the teachings of the Lord. Our leaders, in the 1960s, let us down in this regard, with the praiseworthy exception of Hugh B. Brown. But I also believe the members failed to respectfully let our leaders know that it was time (long overdue, actually) to jettison the Priesthood Ban. And several of those members, including myself, could have done a better job of befriending their African American neighbors. Actions generally speak louder than words.

Good follow up Eric

Love your insights as always. I, too, would like to see us do better to own, apologize for, and make right our collective past with regard to race and civil rights.

Would that we learned the lesson well enough to stand up for our LGBTQ+ brothers and sisters today. We’ve seen a softening in rhetoric, but we still have miles and miles to go. Our leaders are not studying from the best books to understand the science (or the humanity) and continue to defend a position ever more indefensible. And perhaps we as members owe more effort as well. Still, it’s difficult for an organization to make anything more than incremental changes when so many voices are unrepresented and underrepresented where such decisions are made.

Incidentally, I don’t know if you’ve heard of the Beyond the Block podcast, but I think you might find value or interest in it. Between you and the hosts of BTB, I have found my ideal Sunday School.

JTP, I can add nothing to, but wish to echo, your sentiments regarding our failure to be more inclusive when it comes to welcoming our LGBTQ brothers and sisters. Greg Prince, in his most recent book, “Gay Rights and the Mormon Church,” documents that failure in considerable detail. As you say, large organizations, like supertankers, often find it difficult to change direction for the reasons you mentioned.

Thanks for bringing to my attention the Beyond the Block podcast. You scooped me on that one. Having just checked out their website I can already tell James and Derek will most certainly hold my attention. Their backgrounds are most intriguing.

Lastly, thank you for your kind words about my website. It makes you a member of a small, but much appreciated, minority.