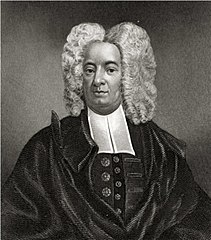

Towards the end of October 1702, the prominent New England Puritan Minister, Cotton Mather, was worried. His preoccupation was not with the ghosts and goblins associated with Halloween, as one might have suspected given his role in the Salem witch trials a decade earlier. Rather, his mind was focused on another invisible purveyor of death: smallpox.[1]

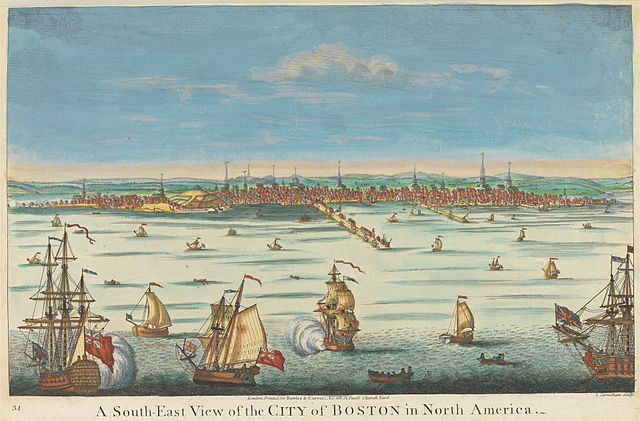

Its reappearance in Boston was not unexpected. The disease seemed to operate on a 20-year cycle for reasons no one understood at the time. But the death toll on this occasion had been horrific: about 1,000 people had perished during the preceding twelve months, representing 14% of the city’s population. Such a mortality rate today would yield more than 600,000 fatalities in the Boston Metropolitan area.

The workload for a clergyman in a crisis such as this—presiding at funerals, comforting bereaved family members, and providing material assistance to those in need—was overwhelming. When members of his flock would ask why God would allow this pestilence to afflict them, he would deliver the doctrinally correct Puritan response: It was the will of the Lord. Perhaps they were being punished for their sins or their faith was being tested. Whatever the reason, the judgments of the Lord were always righteous and true.

Puritan beliefs regarding the origin and purpose of plagues, floods and other disasters can be traced to ancient times. If you’ve ever wondered why the Israelites struggled with polytheism, prompting Jehovah to make it the subject of the first of his Ten Commandments, the reason is pretty straightforward: the most compelling explanation in their minds for both the tragedies and good fortunes that befell mankind was the supernatural.

The Goddess of Rain (“Tefnut” in Egyptian mythology), the God of War (“Ashur” for the Assyrians), along with many other deities, provided a ready explanation for the occurrence of these events. Thus, when the Israelites perceived that the gods of the Canaanites were outperforming Jehovah, they often switched the object of their worship.

Mather’s theological perspective was shared by virtually all of his colleagues. But unlike previous plagues, this one was personal. Mather’s wife and three of his children had contracted the disease and their symptoms were severe.

Not knowing where else to turn, he petitioned the Lord for an understanding of what the future had in store. “God prepare me, God prepare me, for what is coming upon me.”[2] In desperation, he did something he generally counseled his parishioners to avoid: he used the Bible as a fortune-telling device by blindly selecting a passage of scripture for guidance.

His finger landed on John 4:46 which recounts the healing of the nobleman’s son by the Savior. When Mather read the words spoken by Christ before he healed the man’s child—“Except ye see signs and wonders ye will not believe”—he was comforted and overjoyed. For he believed his serendipitous selection of this story was a “sign and wonder” directed at him. He now strove to prove his fealty to the Lord by redoubling his commitment to the spreading of his gospel. His elation and ardor, however, soon dissipated, for shortly thereafter his wife endured great pain and anguish before succumbing to the virus.

Mather’s faith was shaken to the core and he began to question his most fundamental convictions. As to smallpox, his private beliefs began to veer into unorthodoxy: if it were possible for man to find a cure for this disease, would it not be wrong to respond to such a gift by rejecting it? Then, while in the midst of his grieving, which lasted several years, something totally unexpected transpired, an event that would not only alter his life but, arguably, the course of history in North America.

A member of his congregation bestowed upon him a gift. A slave.

At the time Mather received this unusual gift, “the practice of having an African servant living under an English colonist’s roof was well established, but it was not the ‘peculiar institution’ American slavery would become.”[3] Indeed, Massachusetts law safeguarded the freedoms of virtually all classes of citizens; and it even secured certain rights and privileges for indentured servants. In this manner, a sharp distinction was made between servitude and bondage, with the former not being the racially defined scourge slavery was destined to become.

The name Mather chose for the new member of his household was Onesimus, the appellation given by the Apostle Paul to an escaped slave who fled to him in hopes of securing protection from a cruel master. Ironically, Paul at that time found himself a captive, having been imprisoned for his teachings. Once released, he was greatly touched by the loyalty of his new companion, one who became not only his servant but also a servant of Jesus Christ.

Mather’s Onesimus was assigned to perform household tasks and so was given a room in the family home. This permitted him to witness one of the most tragic events in his master’s life: the death of his second wife, Elizabeth Hubbard, and their newborn twins, all of whom succumbed to measles during the epidemic of 1713.

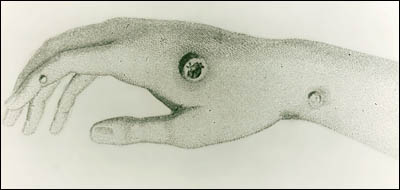

While trying to come to terms with this second calamity, it appears Mather asked his African-born servant whether he had ever had the disease. Onesimus replied, “yes and no.”

Seeing his master’s confusion, he went on to explain a practice in his homeland whereby “healthy young people were exposed to the fluids from the bodies of the ill in order to protect them from the disease.”[4] They, too, contracted the illness, but typically suffered only a mild case, one that strengthened their immunity to the disease. What Onesimus was describing was “variolation,” an early form of inoculation.

When his servant showed Mather the scar on his arm where the operation had been performed, the proverbial light bulb, to use an anachronistic metaphor, lit up in his head. He believed he was now witnessing the fulfillment of the prophecy embodied in the healing miracle performed by Christ for the nobleman.

Upon inquiring further after this procedure, Mather learned that while it was virtually unknown in the New World, it was gaining in popularity in Europe where medical journals had traced its origins to East Asia and its ensuing adoption in Turkey and West Africa. But the inhabitants of those lands were generally regarded as heathens because of their polytheistic beliefs, cultures that also had no qualms about mixing the spiritual with the physical.

The God of Smallpox, according to these communities, was not so powerful that he could not be swayed by human intervention. For this reason, the procedure described by Onesimus was not only a medical instrument, but also a religious ritual.

Regardless of the effectiveness of these practices, Puritans continued to ascribe their origins to witches and evil spirits, and they dismissed the religious beliefs of the African practitioners as mere superstitions. But to Mather, the track record of these treatments was undeniable and appeared to be a divine blessing.

Eight years later, smallpox made another appearance in Boston. Mather, with his expanding knowledge of the science of inoculation, was confronted with a stark choice: should he continue to defend Puritan dogma regarding the source and purpose of natural disasters or did his stewardship require him to urge his followers to take all available steps to protect their lives. He chose the latter, coming out strongly in favor of inoculation and sharing with local doctors and clergymen a plan for combatting outbreaks. But he was vilified for his efforts—not just because his plan was contrary to received doctrine. Inoculation’s association with the primitives of dark Africa continued to render the practice suspect.

Mather did, however, make one convert: Zabdiel Boylston, a local surgeon. Together they authored a pamphlet in 1722—“An Account of the Method and Success of Inoculating the Small-Pox”—and embarked on a proselytizing mission. Mather, for his part, tried to demonstrate the value and importance of cross-cultural learning, likely referencing the words of Paul: “…whatsoever things are true…whatsoever things are just…whatsoever things are of good report, if there be any virtue and if there by any praise, think on these things.”[5]

Notwithstanding the evidence marshaled by Mather and Dr. Boylston, they met with little success and made few converts. Indeed, opposition was so strong that their standing in the community was greatly diminished and Mather was, yet again, pilloried for his heresies. Nevertheless, he did not retreat. He abandoned doctrinal purity in favor of a better way, one grounded in what he believed to be scientific truth. And eventually he carried the day, though not in his lifetime.

Boston in 1722, according to historian Peter Manseau, arguably “marks the birth of the kind of practical pluralism that would later define the American experiment.”[6] Just as the great devotion of the original Onesimus influenced the Apostle Paul, the impact of his 18th century namesake led his master to see that religion and science can compliment each other. Indeed, the influence of Mather’s Onesimus can be found in many contemporary faiths, including Mormonism, where health blessings routinely go hand in glove with the latest medical treatments.

And should you ever find yourself the recipient of a lifesaving vaccine, consider offering a prayer of thanks for these two noble, enslaved men.

[1] Peter Manseau, One Nation Under Gods: A New American History, (New York: Little Brown and Company, 2015), p. 119. I have relied upon this work for most of the material in this essay.

[2] Ibid, p. 121.

[3] Ibid, p. 124.

[4] Ibid, p. 129.

[5] Philippians 4:8 (KJV).

[6] Ibid, p. 140.

I love this story! Thank you for all of your research!

very interesting, thanks

Great story. More broadly, Mormon belief in revelation combined with our understanding of eternal, immutable truths — many still to be discovered, helps us avoid the tendency to be satisfied and complacent with our current orthodoxies. In our search for truth, we seek not change, but a deeper understanding of the way things really are. The scientific method transcends narrower inquiries and opens our minds to expanded vistas of universal truths.

Thank you, Eric. I was totally unaware of the history of inoculations in our country. This also is very timely for me, because yesterday I signed up for my COVID vaccine. Thanks for making this interesting story available to members of our ward.

You are most welcome, Judy, and it’s great to hear that more people are gaining access to the vaccine. It’s remarkable how quickly these companies developed them. But our history teaches us that they didn’t start from scratch; rather, they stood on the shoulders of giants.

Dick, I wholeheartedly concur with your description of our beliefs regarding continuing revelation and the importance of the scientific method in our quest for new knowledge. Such a mindset does help “us avoid the tendency to be satisfied and complacent with our current orthodoxies.” While you framed this principle eloquently, I do not believe that collectively, as an ecclesiastical institution, we always practice what we teach.

Excellent, enlightening article. I love the concept of ‘practical pluralism’. We really can/should learn from everyone around us.

Interesting. Of course at the time of the American Revolution John Adams was having his family inoculated as suggested by Cotton Mather. The treatment involved scraping a smallpox-infected serum into the skin. If the procedure were successful, pock marks would occur in about 10 days. The term “small pocks” led to the name smallpox. People got quite sick with the disease but still most often recovered. George Washington who recovered from small pox was a big advocate of inoculation. In 1770 Edward Jenner (1749-1823), an English doctor, became interested in the idea that previous illness with a disease called cowpox could protect a person from later becoming ill with smallpox. Jenner’s biographer claimed that Jenner heard this folk wisdom from a milkmaid: having caught cowpox from a cow, she believed herself, and her smooth skin, safe from smallpox. In 1796, he demonstrated that an infection with the relatively mild cowpox virus conferred immunity against the deadly smallpox virus. Cowpox served as a natural vaccine until the modern smallpox vaccine emerged in the 19th century. I hate the idea that people equate sickness with wickedness. Let’s remember that the Lord helps those who help themselves. There is room for science and religion to work together. I also second my husband’s comments.

Karen, I too hate the idea of equating sickness with wickedness. Unfortunately, this false belief finds support in a literalistic reading of the scriptures. We fail to understand that the reason the ancients so often attributed every calamity to God was because there was no alternative explanation (e.g., science) readily available.

My philosophy is whenever science offers an alternative explanation for an event described in the scriptures (e.g., the creation of the universe and our world), go with science. God has never evinced any interest in teaching us science. He has his hands full just trying to teach us how to behave.

S. Barnhart, I too like the idea of “practical pluralism.” Too often we reject an idea based on its source, sometimes at our peril.

Thanks for your thoughts in response. Good points.