What is Character? Is it something that can be identified, described or developed? Is character fixed or can it be changed? Does it determine our fate, as the Greek philosopher, Heraclitus, declared? Are the events in our lives merely the manifestation of our individual and collective character, as postulated by Henry James? For centuries, philosophers, theologians, scientists and others have wrestled with the enigma of human character.[1]

A person’s character traits include not only his virtues and flaws, but also morally neutral qualities, such as tendencies, preferences and quirks. And when we assess character, we do not limit ourselves to individuals. We also assign character traits to families, associations, religions, and nationalities.

Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, published in 1840, is a lengthy meditation on the character of the United States and its citizens. He marveled, for example, at how often people joined together in this country under the auspices of new organizations, what he called “associations.” And there were thousands of them: “some religious, some moral, some grave, some trivial, some quite general and others quite particular….”[2] He was, on the other hand, put off by Americans’ incessant pursuit of wealth, along with the unbridled passion with which candidates for public office—and their supporters—championed their cause.[3]

The character of individuals and the groups to which they belong are often insightfully portrayed in works of fiction. Anthony Trollope’s Chronicles of Barsetshire, for example, cleverly depicts the lives and social structures of the English clergy and landed gentry during the Victorian era.

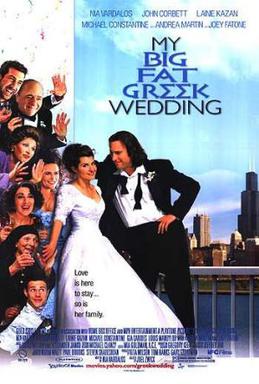

On the big screen, the romantic comedy, My Big Fat Greek Wedding lampoons the culture and citizens of the Hellenic-republic. My Greek friends loved it, though one of them did say the writers crossed the line when they showed the family roasting a lamb in their front yard. “Any self-respecting Greek would only do that in the back,” she said with a smile on her face.

Our church and its culture have also been parodied, both from within and without. Thirty years ago, Sunstone, a scholarly Mormon publication, ran an “exposé” about an early-morning Seminary teacher who had made an astounding discovery. One Monday morning she stumbled upon an envelope in a church hymnal marked “confidential.” It contained a document titled, “Form Talk for High Councilors – The Diaspora Stake.”[4]

This template instructed stake representatives to begin their remarks by saying: “I bring you greetings from the stake presidency, and I testify to you that these good brethren are called of God and receive inspiration in their stewardship over this part of the Lord’s vineyard, and they have a genuine concern for each and every member of this great stake.”

Next, they were reminded to compliment any youth speaker who was on the program and then to say they were “touched by the wonderful” musical number. Prefacing their remarks with a little humor—perhaps a short anecdote from Readers Digest—is recommended. And when you turn to your assigned topic, you should always begin by reciting its definition from a dictionary. And so on.[5]

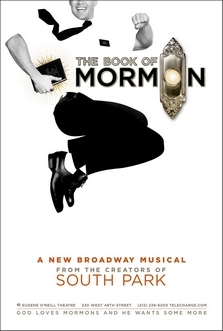

The Book of Mormon musical also pokes fun at our idiosyncrasies, sometimes with penetrating insight. One of the most memorable lines in the production is delivered by Elder Kevin Price, who is serving a mission in Uganda: “I BELIEVE,” he loudly sings, “that in 1978 God changed his mind about black people.” This line is funny—in part because it is true.

Parodies are humorous exaggerations done typically for comic effect. They are not meant to capture the complexity and diversity of the members of an ethnic group, country, or religious tradition. Nobody, after all, is ever just one thing.

In recent years, however, many have sought to minimize, if not eliminate altogether, the intricacies and competing allegiances of the modern individual. People instead are encouraged—often pressured—to affiliate with a particular group (or subgroup) according to an identity marker, such as their race, gender, or ethnicity. Each tribe has its own doctrines and ideologies, and orthodoxy is strictly enforced.

A black intellectual, for example, who dares to question the merits of affirmative action or the existence of systemic racism is vilified as a traitor. Similarly, a senator who challenges the actions of a president who is a member of his own party nowadays can expect to be insulted and pilloried for his alleged disloyalty.

Insistence upon conformity is not unknown in our religious community. For example, those who question whether there was a universal flood, the Tower of Babel was real, or the received wisdom on other matters are often asked to keep their opinions to themselves since the church has made it clear this is not what Latter-day Saints are supposed to believe.[6] But when such intolerance is carried to an extreme, there are often unintended consequences.

Several years ago we were in a ward where the bishop, at the urging of the stake president, made it a priority to get every young man to wear a white shirt on Sunday. Those who refused were generally not allowed to administer the sacrament. One young man—I will call him “Scott”—declined to conform.

While Scott’s mother was active in the church, his father was not. But one Sunday his father did attend sacrament meeting in order to support his son, who was a member of a vocal quartet performing a special musical number that day.

After the meeting concluded, a young man marched up to Scott’s father and asked, “When are you going to make your son wear a white shirt?” The father replied, “Never,” and walked away.

Word of this encounter found its way back to the bishop who was mortified. He was not angry with the boy, but with himself for having assigned a higher priority to the color of a young man’s shirt than to the content of his character. Nonconformists, he discovered, sometimes are not the ones who need correction.

One of my favorite Mormon mavericks was J. Golden Kimball, a General Authority who served in the First Council of the Seventy from 1892 until his death in 1938. He was affectionately known as the “swearing cowboy” because he worked for a time as a mule skinner, a job impossible to perform, he said, without using profanity. In a word, he was colorful.

J. Golden was confident there was no inspiration or revelation involved when he was called to be a General Authority; rather, it was simply the result of “relation.” “If Heber C. Kimball wasn’t my father, I wouldn’t be a damn thing in this church.”[7]

When he set off on his mission as a young man, he said his knowledge of the scriptures was so pathetic that he thought “epistles” were the wives of apostles.[8] Several years later, while giving a blessing to a Russian member whose name he simply could not pronounce, he said, “Oh, Father, you know who this is anyway,” and then proceeded.[9] His ringing endorsement of the United Order—“Brothers and Sisters, I believe in the United Order! I will throw all my debts in with you any time!”—was certainly unorthodox, though well received by the congregation.[10]

J. Golden’s irreverence resonated with many church members who, like himself, just didn’t fit the mold. He was also known as someone who wouldn’t just give them a canned response to their questions.

One time, after a church meeting, a distressed woman approached Brother Kimball and told him about the sudden death of her brother who was hit by lightning as he stood in his wagon. He was a fine man, she said—a bishop, a schoolteacher, and a devoted husband and father—and the whole town came to his funeral. J. Golden offered his most sincere condolences, but the tragic loss of her brother wasn’t what was bothering her.

She said: “I miss him but I know I’ll see him again. My real problem is my younger brother. He’s no good at all. He smokes, he drinks, he gambles, he cheats on his wife. He’s a terrible father and husband—and he’s still alive! I can’t figure it out. Why would the Lord take the good one?!?”

She started to cry, so Brother Kimball put his arm around her until she regained her composure. He then said, “Sister, do you know what it is? The Lord doesn’t want that jackass brother of yours any more than you do.” The woman paused to consider his response and was convinced it was better than any other explanation she had received, and went away happy.[11]

I’m confident this sister knew that J. Golden wasn’t speaking literally. Rather, he dispensed with the pat explanations—“this is all part of God’s plan;” “everything happens for a reason”—in favor of a lighthearted way of telling her that “poop happens,” sometimes for no apparent reason, and that the tragedies in our lives have no meaning, save how we respond to them.

Our church doesn’t just need men and women of good character in positions of leadership. It needs characters, too. Along with a handful of iconoclasts and a few oddballs. Individuals who are willing to take risks and explore new ideas.

Should some take issue with their perspective, so much the better. Diversity of thought and vigorous debate are often catalysts for the discovery of new truths and new ways of doing things. During the first 100 years of the church’s history, open disagreements in the higher ranks were commonplace and the members were mature enough to accept them. I think we still are.

Most of all, we need leaders who will make us laugh, especially at ourselves. Though Heber J. Grant was sometimes perturbed by J. Golden’s behavior, he saw how his levity could reduce divisions within a community. His self-deprecations caused people to see him as an equal, not as a member of some ecclesiastical royalty. Here was a General Authority who was struggling with his own foibles, backsliding at times, and then promising to do better. And no one slept when he spoke. Ever.

Among those whom I like or admire, I can find no common denominator, but among those whom I love, I can. All of them make me laugh.

W. H. Auden

[1] Marjorie Garber, Character: The History of a Cultural Obsession, (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2020), p. 4.

[2] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Arthur Goldhammer, translator, (New York: Library of America, 2004), p. 595.

[3] Ibid, pp. 152-153.

[4] “Form Talk for High Councilors – The Diaspora Stake, Sunstone, Vol. 14, No. 3 (June 1990), p. 50.

[5] I shared this with my kids during a family home evening and, to this day, they struggle to maintain a straight face when they hear a high councilor assure them of the love and concern the stake presidency has for each member. If you’ve ever wondered why the image on the landing page of my website is the painting, “The Death of Socrates,” it is because we both stand accused of corrupting the youth.

[6] Donald W. Parry, “The Flood and the Tower of Babel,” Ensign, (January 1998) (“There [are] those who accept the literal message of the Bible regarding Noah, the ark, and the Deluge. Latter-day Saints belong to this group.”). Old Testament Gospel Doctrine Teachers Manual, (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Salt Lake City Utah: 2001), pp. 24, 40, 65.

[7] James Kimball, J. Golden Kimball Stories, (Salt Lake City, Utah: Whitehorse Books, 1999), p. 29.

[8] Ibid, p. 15.

[9] Eric A. Eliason, The J. Golden Kimball Stories, (Urbana and Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2007), p. 97.

[10] Ibid.

[11] James Kimball, pp. 37-38.

As always, very thought provoking. I LOVE characters!

Thanks, Karen. And I love them, too. I’ve been called one on more than one occasion and I always consider it to be a compliment.

A nice exploration. I enjoyed this one particularly. As always, the article is well written. As always, it takes a character to recognize a fellow character but, as you say, that’s a great compliment. I agree.

Thanks, Thorpe. I didn’t think you would disagree with my self-characterization.

This reminds me of when my cat died. Several weeks later, I would still weep at the thought of him. I was sitting on the couch crying one afternoon when my daughter (I’ll let you guess which) saddled up beside me, patted me lovingly on the shoulder and said, “You know, mom, he was just a cat!” I couldn’t help but laugh. I love the characters in my life that are willing to see a different angle, give us some perspective, and march to their own convictions rather that social dictates. We need characters to keep us from being too serious and dour!

That’s a delightful story, SBarnhart. It’s a shame that we stifle much of the candor and perspicacity of our youth owing to peer pressure and social conventions. It’s one of the reasons I so enjoyed the years I have spent serving as the pianist in Primary. I actually believe I’ve learned more about the gospel in Primary than I ever have in a Sunday School class or priesthood meetings.