The majority of biblical scholars believe the infancy narratives found in Matthew and Luke are ahistorical (i.e., not factual).[1] Rather, they are an example of a creative genre of Jewish theological writing known as Haggadah, meaning “narrative.” The author starts from a scriptural text—the Old Testament, in the case of Matthew and Luke’s birth stories—and then improvises liberally, using symbolism, typology and allegory “to create a new story that reapplies the truths, hopes, patterns and meanings of the scriptural past to the present.”[2]

In an essay I penned last year, I discussed the symbolic significance of the Magi and the Old Testament passages Matthew drew upon to explain how the Savior’s message would be received by the Jews and the Gentiles. This essay picks up where the previous one left off: the story of the Massacre of the Innocents and the flight of Joseph, Mary and the baby Jesus to Egypt. The most common reasons why most scholars believe this account is not historical are the following:

• This story is irreconcilable with many aspects of Luke’s infancy narrative where no reference is made to Egypt and the family returns to Nazareth a few months after Christ’s birth.[3]

• Neither Mark nor John makes any mention of Christ’s miraculous birth and rescue from the clutches of Herod. Further, the stories regarding Jesus’ ministry in all four gospels were clearly shaped with no knowledge whatsoever of the infancy material found in either Matthew or Luke, leading most scholars to conclude that they were the last chapters added to their two Gospels.[4]

• Paul likewise fails to mention these events, which is especially odd since his dominant theme is the miracle of the Savior’s atonement, resurrection and ascension to heaven. Given the significance attached by the ancient world to celestial signs and supernatural interventions, it’s hard to believe he—or Mark and John—would not have employed these events to burnish the Savior’s bona fides.

• There is no corroborative account of the Massacre in the historical record. The failure of Josephus to mention this crime is especially noteworthy since he hated Herod and otherwise documented all of his atrocities, especially during the final years of his reign.

• In rebuttal to the previous point, some emphasize the small size of Bethlehem’s population, estimated by most historians to have been around 500 – 1,000 people in the first century.[5]

As a result, the maximum number of male infants, age zero to two, slaughtered by Herod would only have been around 25, perhaps escaping the attention of Josephus and others. This is a fair observation, but begs an obvious question: why would Herod need the wise men to provide him with the location of Joseph and Mary’s residence, since, according to Luke, the shepherds, after visiting the Christ child on the evening of his birth, “made known abroad the saying which was told them concerning this child.”[6] Even royalty from other lands knew of his presence; hence the arrival of the magi. Virtually everyone in this very small community and the surrounding area would have heard about these miraculous events, if Luke and Matthew are to be believed, so all Herod would have needed to do was ask for directions. Or follow the wandering star.[7] Or dispatch his spies to follow the wise men.

• Lastly, as noted by the Catholic scholar Raymond Brown, “the infancy stories echo Old Testament stories to an extent unparalleled in the rest of the Gospels.”[8] In other words, the textual connections between the birth narratives and certain stories in the Hebrew Bible are far too numerous to be coincidental. Further, the manner and style in which the Old Testament is employed by the evangelists in the first two chapters of their gospels can be found nowhere else in the New Testament. [9]

So, if the male infants of Bethlehem were never slaughtered, what is the purpose of this story? To begin with, it tells us something about Joseph, who receives multiple revelations via dreams, warning him to take his family to Egypt to escape Herod’s evil designs, followed by an “all-clear” dream telling him Herod had died and it was okay to go home.

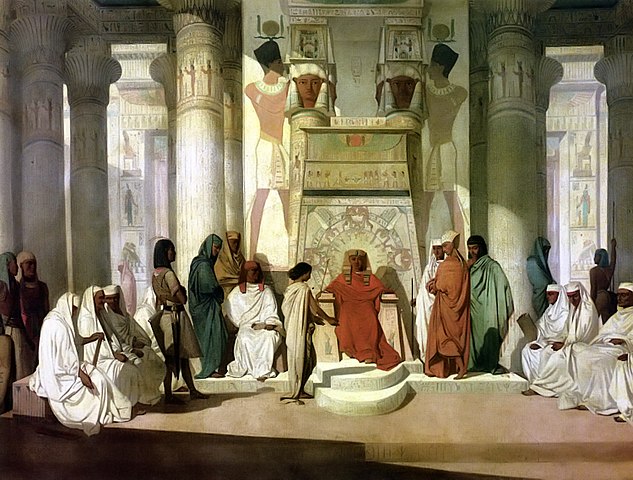

He is consciously portrayed by Matthew in the image of the Old Testament patriarch Joseph, “the master of dreams,” who went down to Egypt to escape an attempt on his life and, while there, rose to a position of prominence in the royal court by interpreting the nocturnal visions of others.

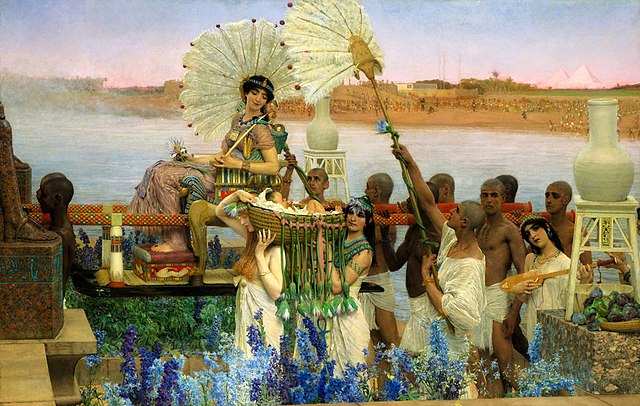

But what is most striking about this story is how we find echoes of Joseph’s life—and, more importantly, that of the Christ child—in the life of Moses.[10] The Pharaoh was forewarned by his soothsayers that a child was about to be born who would threaten his kingdom, so the Egyptian decided to kill all of the male children of the Hebrews. The Pharaoh’s plans, however, were revealed to Moses’ father in a dream. When his wife gave birth, the couple took steps to protect the child.[11]

There is, however, an even more powerful message Matthew is trying to convey. The Old Testament prophet revered by the Jews more than any other was Moses, the man who led them to the Promised Land. No single event is referenced in the Hebrew Bible with greater frequency than the Lord’s constant reminder to his wayward people, “I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt so that you would not be their slaves, and I broke the bars of your yoke and made you walk erect.”[12]

Thus, Matthew is portraying Jesus as the “New Moses”[13]—one far greater than the first—who offers not a terrestrial estate but a celestial domain. And the analogies to Moses continue throughout his gospel. For example, the most profound sermon of Christ’s ministry—The Sermon on the Mount—is an obvious parallel to Mount Sinai where Moses delivered the Torah to Israel. Indeed, Matthew sets six different scenes on mountains to make the connection clear and to show the Israelites that Jesus is simply picking up where Moses left off.

Finally, he is also telling us something about who will ultimately be more receptive to Christ’s message. His gospel was composed at a time when Gentiles dominated the Christian sect. They were his target audience, and the Magi are the first Gentiles drawn to the Savior. But not by prophecy. Instead, it is through nature—the wandering star hovering over Bethlehem—and their faith that they find Jesus.

By contrast, Herod, a practicing Jew, had the rich body of Jehovah’s teachings found in the Torah and the Books of the Prophets, but chose to ignore the prophecies concerning the birth of the Messiah,[14] like many other members of his faith. But the Gentiles needed the Jews and their sacred texts to fully understand Christ’s identity and the doctrines of salvation.[15]

The Old Testament foreshadowing techniques and symbolism employed by Luke and Matthew elude us for many reasons. For example, the primary (and often exclusive) yardstick by which we measure truth is whether it is historically or factually accurate. The ancients, by contrast, frequently preferred allegory, myth, numerology and even satire to convey their ideas and beliefs regarding faith and the divine. “Truth,” for them, came in many guises.

We also, as I have often observed, fail to read sacred texts in their proper cultural, historical and geographical context. And we assume their authors perceived the world, and lived and recorded their lives and spiritual experiences, the way we do. They did not.

Further, we rarely stop to consider the textual context of a story—i.e., its relationship to other events, allegories and revelations in the same body of scripture. The infancy narratives of Matthew and Luke are a prime example.

Paul’s epistles, the first books chronologically of the New Testament, contrasted the gloriousness of the resurrection with the lowliness of the Savior’s ministry, suggesting that Christ did not acquire divine status until he was resurrected. But as the early Christians began to reflect on the mystery of the Savior’s identity and compile a record of his ministry in the Gospels, the scales fell from their eyes and they realized that Jesus was the Messiah and Son of God during his ministry, which began, according to Mark with his baptism by John the Baptist. Matthew and Luke press Christ’s divinity back even further—to his conception in the womb—and the Gospel of John, the last one written, extends it back further yet: to the pre-existence (“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”)[16]

These marvelous textual connections help us see how the Lord added, line upon line, to the understanding of the early Christians regarding his divine identity and nature. We, in turn, are the beneficiaries of their learning and experiences, as documented in the New Testament, and share with them the knowledge that Jesus the Christ, whose birth we celebrate today, truly was the greatest man to have walked the earth.

[1] See, e.g., Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in the Gospels Matthew and Luke, (updated ed.), (New York, New York: Doubleday, 1993), pp. 32-37, 188-189; Paul L. Maier, “Herod and the Infants of Bethlehem,” Jerry Vardaman and Ray Summers(eds.). Chronos, Kairos, Christos II: Chronological, Nativity, and Religious Studies in Memory of Ray Summers, (Mercer University Press., 1998) pp. 170–171.

[2] Jeffrey John, The Meaning in the Miracles, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2004), p. 8.

[3] You can say the same thing about Luke’s account of Christ’s birth: it doesn’t mesh with Matthew’s. This, among many other reasons, is why most scholars likewise believe Luke’s infancy narrative is ahistorical.

[4] The Birth of the Messiah, pp. 31-32.

[5] Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary, Clinton E. Arnold, Gen. Ed. (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2002), p. 19.

[6] Luke 2:17 (KJV).

[7] To the above, Raymond Brown adds the following arguments: “The narrative of how Herod assembled the priests and scribes for consultation betrays no awareness of the bitter opposition that existed between Herod and the priests.” * * * * “One can imagine the impression that exotic magi from the East with royal gifts would make in a small village; yet when they go away, Herod’s intelligence system cannot discover which child they visited.” The Birth of the Messiah, pp. 188-189.

[8] Raymond E. Brown, An Adult Christ at Christmas, (Collegeville, Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1988), p. 5.

[9] The Birth of the Messiah, pp. 37-38 (“One is hard pressed to find elsewhere in the Gospels theology so succinctly and imaginatively presented.”)

[10] The HarperCollins Study Bible (rev. ed.), Harold W. Attridge, Gen. Ed., (New York, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2006), p. 1668, 1669; The Oxford Bible Commentary, John Barton and John Muddiman, Eds. (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 850.

[11] The Birth of the Messiah, pp. 228-229.

[12] Leviticus 26:13. By my count, there are close to 100 similar references to this event.

[13] The Jewish Annotated New Testament (2nd Ed.), Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler, Eds., (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 14; see also Amy-Jill Levine, Sermon on the Mount: A Beginner’s Guide to the Kingdom of Heaven, (Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon Press, 2020), pp. xvi-xviii.

[14] Matthew 2:5-6 (KJV).

[15] An Adult Christ, p. 13.

[16] The Birth of the Messiah, pp. 29-31.

You always open my eyes up to a bigger way of seeing things. Love it! Thank you for these thoughtful and thought-provoking essays.

You are most welcome, Stephanie. And thank you for being a loyal reader.

Happy New Year!

What an insightful reading! Now that my retirement is almost here, I look forward to taking some time and going back and reading all of your essays.

Thank you for your kind words, Doug, and, again, for taking the time to read my stuff. Your opinion is one of those I prize the most—not because you always agree with me but because you have a very diplomatic way of pointing out my mistakes and questioning my opinions. Most people, just say: “Facer, you idiot! What were you thinking?!?”

Again very interesting. Enlightening to contemplate how each of us progress in thought through stories, similarities, allegories, and parables toward pure doctrine and basic principles. Somehow it doesn’t really matter if the “story” details are accurate as long as they lead us in the right direction.

Well said, Karen. It is of no moment whether a truth is being taught via an actual historical event, a myth, a work of satire or of poetry, or a parable.

Throughout all human history, different cultures have employed different mediums to convey what they believed was true. It is both arrogant and chauvinistic to think that the means by which we attempt to teach each other the truth are superior to those used by our ancient ancestors.