Note to reader: I am republishing this essay—with substantial revisions and additions—to mark the 45th anniversary of the day on which the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints lifted its “Priesthood Ban,” becoming the last major Christian religion to accord equal treatment to individuals of African descent.

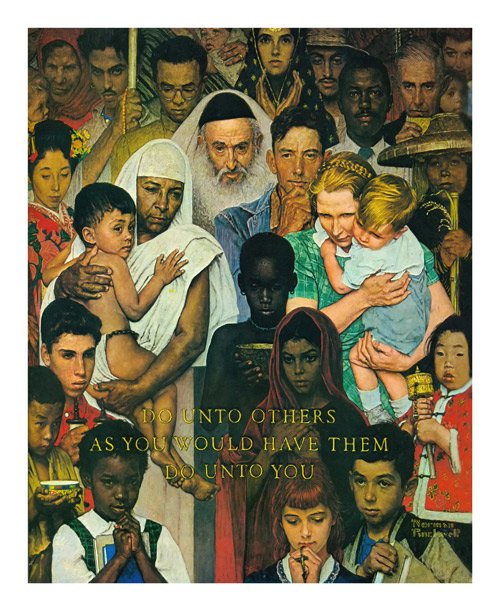

The whole concept of…the image of God is the idea that all men have something within them that God injected…that every man has a capacity to have fellowship with God. And this gives him a uniqueness, it gives him worth, it gives him dignity. And we must never forget this as a nation: There are no gradations in the image of God. Every man from a treble white to a bass black is significant on God’s keyboard, precisely because every man is made in the image of God. One day we will learn that….

Martin Luther King

One of our favorite family traditions when I was young—one we shared with millions of other Americans—was gathering around the television every Sunday evening to watch Bonanza, an American Western set in Nevada near Carson City. The show chronicles the adventures of the Cartwright family, owners of one of the largest ranches in the state: the Ponderosa.

The family patriarch was the thrice-widowed Ben Cartwright (Lorne Greene), who had three sons of varying temperaments. The show, which ran a record 14 seasons on NBC, was popular because it offered both comedy and drama, and told compelling stories about the family, and those in its orbit.

Of all the episodes I watched there is only one I remember in any detail. It was called “It’s a Small World,” and it taught me an important lesson.

The plot revolves around a dwarf—George—who vows to keep a promise he made to his wife on her deathbed: find a job outside the circus so their newborn daughter could have a stable life. He turns to Ben Cartwright for help who recommends him to the town banker, Mr. Flynt, because George is good with numbers, having kept the books for the circus. The prospect of filling a vacant teller slot at the bank thrills Flynt, so he agrees to interview him. But when he meets George, he recoils at the prospect of hiring a little person.

Unable to find work and needing money to feed his daughter, George breaks into the bank after hours and takes what he needs. But he is soon caught and arrested.

Cartwright promptly comes to his defense, but the sheriff tells him his hands are tied—unless he can get Flynt to drop the charges. Ben then heads directly to Flynt’s office where he implores the bank owner to drop the charges, even offering to cover the cost of any unrecovered funds, but Flynt is unmoved. Whereupon the following exchange occurs:

Cartwright: “I’m just asking for a little compassion—for a man who has just lost his wife, has a brand new baby daughter…

Flynt: “He didn’t have to steal.”

Cartwright: “He tried to get a job and he couldn’t. You ought to know that.”

Flynt: “Ah … yes … I knew we’d get around to that. It was my fault because I didn’t give him a job. Well, I didn’t force him to steal; it was in him. I tried to tell you that, Ben.”

Cartwright: “Yes, you did. You did try to tell me that and I almost forgot. He’s a thief because he’s smaller than you are—if that’s possible.”

Flynt: “Ben, I told you yesterday. He should live with his own kind! If God had meant us all to live together he would have made us all the same!!”

Cartwright [pauses, inhales, and quietly says, before walking out of Flynt’s office]: “You may be right. And I may be very wrong. And maybe you know something I don’t. You see … I don’t know how tall God is.”

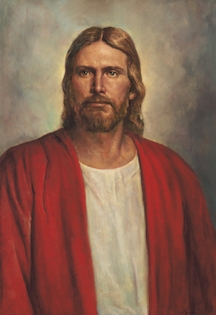

That simple declarative statement—“I don’t know how tall God is”—taught me that it’s a terrible mistake—and terribly arrogant—to presume we know anything about God’s physical characteristics or who is like him and who is not. So, I have always been perplexed by the unwavering position taken by the Mormon Church regarding the complexion of Christ: he’s Aryan white. Most church members, however, would be surprised to learn that the origins of this dubious doctrine can be traced, in part, to an attempt by outsiders to paint early Latter-day saints as a racial minority.

In recent years, the church has been trying to distance itself from its racialized past by highlighting the following verse from its scriptural canon: “[The Lord] denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female; and he remembereth the heathen; and all are alike unto God, …”[1] Sadly, this verse was perceived by the church in the 19th century as a potential threat, if not to its actual survival, then, at the very least, to its ability to win new converts.

During the Missouri and Nauvoo years, detractors and former Latter-day Saints began to characterize Mormons as “non-white.” They accused the church of being too inclusive, of welcoming to God’s earthly family alien individuals of all classes and colors. In the 1830s Edward Strutt Abdy, an English legal academic and abolitionist who toured America, noted that these allegations were validated by the above passage from the Book of Mormon. Simply stated, this text espoused an open racial vision too progressive for 19th century America to stomach while in the midst of a vast internal struggle over the future of slavery.[2]

Efforts to combat these perceptions soon began to influence the theology and politics of the Mormon Church. In 1849, Brigham Young instituted the Priesthood Ban, which barred all Black men from receiving the priesthood and prohibited all African American members from entering the church’s sacred temples. Then, three years later, the prophet declared himself a “firm believer in slavery” and encouraged the State legislature to pass a bill legalizing a form of involuntary servitude in Utah. Which it promptly did.[3]

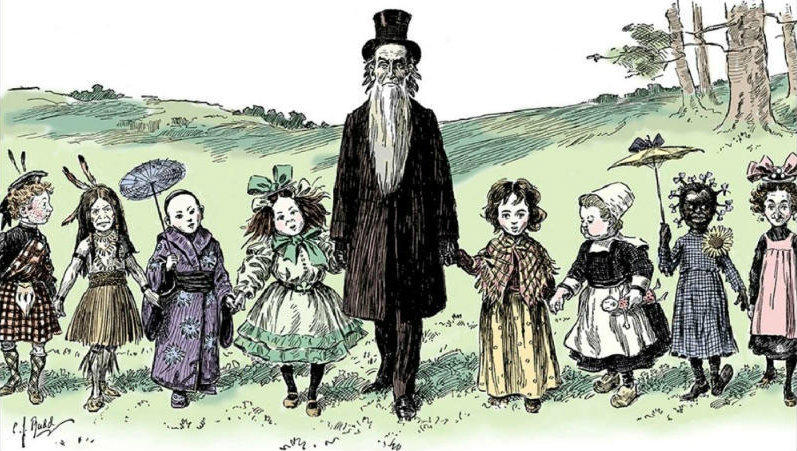

Nevertheless, outsiders continued to treat Mormons as racially suspect, as illustrated by this cartoon from the April 28,1904 edition of Life magazine, which appeared with the following caption: “Mormon Elder-Berry—Out with His Six-Year-Olds, Who Take After Their Mothers.”

It was published while the U.S. Senate was deciding whether the first Mormon ever elected to the Senate, Reed Smoot, would be allowed to take his seat. The cartoon was not only meant to attack polygamy, which was still being practiced in the church, but also to resurrect 19th century stereotypes of Mormons as a mixed, mongrel race.

To further reinforce its “whiteness,” the church responded with images of its own: artistic portrayals of Jesus as White Anglo-Saxon Protestant. To justify its depiction of Christ as Caucasian, it reimagined God’s creation of man.

In 1868, George Reynolds, a member of the First Council of the Seventy taught that, “when God made man in his own image … he made him white. But he didn’t stop there. All of God’s “favored servants”—prophets, apostles, and, of course, his Son—were gloriously white.[4] The Bible’s failure to posit a connection between skin color and God’s favor did not concern Reynolds.

Various passages in the Book of Mormon were also cited as proof of Christ’s white complexion. Further, in the twentieth century, prominent church leaders embraced Native American legends about a “Great White God”—including them in missionary tracts—and of the “whitening of converted Indians” which occurred when they were placed in Mormon homes.[5] But such literalistic interpretations of scripture completely miss the metaphorical meaning of these passages, where the focus is on purity, not skin color.6[6] Moreover, they fail to acknowledge that Joseph Smith’s translation of the Book of Mormon was undoubtedly influenced by the world in which he lived, one where race and the spread of slavery dominated political discourse.

In 2020, the church doubled down on its portrayal of Christ when it announced that all artwork in church foyers would be limited to 22 images featuring a white, blonde, and blue-eyed European Jesus. This decision is hard to reconcile with an ecclesiastical organization that bills itself as a “worldwide church.” And while we do not know what Christ looked like, we are confident he was not a blue-eyed European.

In his First Vision account, Joseph Smith describes seeing two personages “whose brightness and glory defy all description.”[7] Nowhere does he say they were white; rather, they simply radiated a bright and glorious light. Strikingly, Smith’s description of God the Father and his Son has numerous counterparts in the Bible and the writings of other ancient faith traditions.

For example, Jehovah is often described in the Old Testament as a personage “wrapped in light as with a garment” and “clothed with glory and splendor.”[8] As noted by the biblical scholar Francesca Stavrakopoulou, this is not hyperbole or a theological metaphor. Rather, “in its biblical (Hebrew) context, [it] is the technical terminology used to describe the palpable, gleaming radiance emanation from God’s body.”[9]

Many of the Dead Sea scrolls reinforce this image of Jehovah. This Jewish sect counted themselves among the righteous, “walking in the light” of an archangel called the “Prince of Light,” while their adversaries were led by the “Angel of Darkness.”

Christ, even in his pre-resurrection form, was described in similar terms. Echoing the story of Moses’ encounter with God on Mount Sinai, the three synoptic evangelists described the Savior’s transfiguration on a high summit in similar terms. “His face shone like the sun,” according to Matthew, while Luke speaks of his master’s “radiant glory.”[10] John, who proceeds from the assumption that Jesus was fully divine at birth, describes him as the “light of the world,…the life and light of all people…true light that enlightens everyone.” As noted by Professor Stavrakopoulou, these were not theological abstractions. Christ is the personification of the divine light of creation, standing in opposition to primordial darkness and disorder.[11]

Heavenly radiance was so central to the Ancient Christians’ understanding of divinity that it played a defining role in establishing the doctrine of the Godhead in what came to be known as the Nicene Creed. It speaks of Jesus as the “only begotten … from the substance of the Father, God from God, Light from Light. True God from True God, begotten, not made, from one substance with the Father….”[12]

A century or so later, however, certain Christian writers began to attach a different connotation to light and dark. “Light” became “white” and “darkness” was used pejoratively to describe those with black skin. As Professor Stavrakopoulou notes, this was a radical departure from the teachings of Judaism and those of Graeco-Roman religions which often associated black skin “with beauty, majesty and wealth.” Suddenly, the Devil himself—the Angel of Darkness—came to be known as the Black One.[13]

Then, around the end of the fifteenth century, the story of Ham, son of Noah, was perverted into an anti-black myth of African origins. Self-described “biblical scholars” invented a false etymology for the Hebrew word translated as “Ham,’ associating it with words such as “dark,” “black,” and ultimately “sin.”[14]

The “curse of Ham” became a scriptural proof-text for many Christian faiths, including Mormonism, endorsing the belief that black-skinned people are a divinely ordained caste of slaves. Indeed, during the pre-Civil War debates on abolition, Joseph Smith used this perverted scriptural interpretation to argue against the immediate freeing of the slaves, saying that “the curse has not yet been taken off the sons of Canaan, neither will be until it is affected by as great power as caused it to come.”[15] The Quakers, by contrast, seemed to be more attuned to the “great power” of which Smith spoke. They had long been opposed to slavery and even opened their schools to black students—at least until their teachers and schoolmistresses were arrested and sent to jail for violating laws prohibiting the education of the children of slaves.[16]

But at the end of the day, we are still left with an unsolved mystery: what color is the divine being that emanated the light Joseph Smith, Moses and other visionaries saw? What is the complexion of the Lord? I do not know the answer to this question, and I don’t believe any mortal does. But I have a theory, one I arrived at by blending modern and ancient scripture with science.

The first clue is the Israelites’ version of the ancient flood myth, Noah and the Ark.

After the waters of the deluge receded, God promised Noah and his descendants that he would never again visit such a cataclysm upon the earth and placed a rainbow in the clouds as a token of his covenant.[17] For Jehovah, this meteorological phenomenon also served as a metaphorical bridge between heaven and earth, and created a divine link between one dispensation and another.

Although the Israelites did not understand that a rainbow—a spectrum of light in the sky—is caused by the refraction and dispersion of light in droplets of water, their ancient cosmology clearly positioned God in the heavens and frequently associated him with the Sun. Christ reinforced that belief when he declared that he (as previously noted) is “the light of the world.”[18]

When we apply our knowledge of physics and optics to this metaphor, it acquires additional layers of meaning. The light emanating from the Sun contains all colors of the spectrum, including some we cannot see, such as infrared light, along with radio and ultraviolet waves. The invisible portions of the spectrum, like the Lord, are on the other side of a veil, serving as a reminder that mortal eyes have limited vision and perspective. And just as the moisture in clouds was the medium employed by God to reveal himself to Noah in all his many colors, we too must pass through water—the waters of baptism—in order to regain his presence.

The star that lights our solar system, however, is partial to one color in particular: green. Light arrives from the Sun as photons from different portions of the spectrum, but the Sun emits strongest in the green part of the spectrum. This is why the last color your eyes are able to detect as twilight draws to a close is green. All stars have unique spectral signatures, so the disproportionate number of green photons is one of the Sun’s defining characteristics.

Green. The color of life. The color of renewal, rebirth and growth. The color of hope, of better days to come. It both calms and revitalizes, instilling a sense of peace and harmony. It is the defining color of the mother of our world: Nature.

The prophet Jacob employed his own Technicolor metaphor when he bestowed upon his youngest son, Joseph, a “coat of many colors.” Such a robe was a sign of royal status, authority, and favor.[19] It was given to Joseph because his father knew he was destined to be a leader of nations. He fulfilled that prophecy by rising to a position of great power in a foreign land, one where the rest of his family eventually found refuge because of Joseph’s stature in Egypt.

As the twelfth-century French Rabbi and scholar, Joseph ben Isaac (aka, Bekhor Shor) observed, even though we can only tolerate looking directly at the Sun for a brief moment—just as Moses could only endure God’s glory “as it passed him by”[20]—we can gasp in wonder at the Sun’s afterglow and the beauty it both creates and allows us to see.[21] And when people gaze at God’s rainbow, they see themselves—not alone but as part of the family of man. They are clothed, as Joseph was, in a panoply of colors and feel a connection with, and responsibility for, those around them.

God’s light, when dispersed, gives our world it’s vibrant appearance and diverse peoples. Their differences are to be celebrated, not homogenized and correlated. “All are alike unto God” just as they are. God glories in our differences. He wishes to transform us spiritually, not physically. And when that transformation occurs all colors are integrated, becoming gloriously bright while simultaneously retaining their individuality. This, I believe, is the color of God.

[1] 2 Nephi 26:33.

[2] W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Struggle for Whiteness, (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 23, 270-271.

[3] Joanna Brooks, Mormonism and White Supremacy: American Religion and the Problem of Racial Innocence, (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2020), p. 30.

[4] John G. Turner, The Mormon Jesus: A Biography, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 2016) pp. 250-251.

[5] Ibid, p. 253.

[6] Douglas Campbell, “‘White’ or ‘Pure’: Five Vignettes,” 8 No. 1, Dialogue: Journal of Mormon Thought 29, no. 4 (Winter 1996): pp. 119-135.

[7] Joseph Smith—History, 1:17.

[8] See, e.g., Deuteronomy 33:2 (NRSV); Isaiah 60:1-2 (NRSV); Ezekie4l 1:27-28 (NRSV); Job 37:22; 40:10 (NRSV); Psalm 104:2 (NRSV).

[9] Francesca Stavrakopoulou, God: An Anatomy, (New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022), p. 176

[10] Matthew 17:2 (NRSV); Luke 9:31-32 (NRSV).

[11] God: An Anatomy, p. 180; John 1:3-5, 9 (NRSV).

[12] J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, (fifth edition), (London: A & C Black, 1977), p. 232 (emphasis added).

[13] God: Anatomy, pp. 184-85.

[14] Ironically, the Bible associates whiteness, not blackness, with sin. When Jehovah chastised Miriam for questioning the decision of her husband, Moses, for taking a Cushite woman as his second wife, she turned “white as snow.” Numbers 12:10. And the bride of the Song of Solomon, often regarded as a type of the Church, was black as well. (Song of Solomon 1:5.)

[15] Religion of a Different Color, p. 125.

[16] Ibid, pp. 116,122.

[17] Genesis 9:13 (NRSV).

[18] John 8:12 (NRSV).

[19] Zondervan Illustrated Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament: Volume 1, Gen. Ed. John H. Walton (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2009) p. 121.

[20] Exodus 33:19-23 (NRSV).

[21] William H. Propp, Exodus 19-40: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, (New York, New York: Doubleday, 2006), p. 608.

This reminds me of Betty Eadie describing her search for the colors she experienced during her near-death experience and how she ultimately had to admit what she searched for cannot be found on earth—mortal eyes cannot comprehend what she saw, albeit briefly, on the other side. We’re probably in need of a little more transformation to see the light

Well said Tina, though I must disagree with you on one point: we need not a little, but a whole lot of transformation, to see the light.