The year is 1648 and most of Europe is in tatters. The Dutch War of Independence between Spain and the provinces—what are today the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg—has raged for 80 years, while The Thirty Years War within the Holy Roman Empire has laid waste to much of the continent. The population of Germany alone has fallen from 21 million to approximately 13 million.[1]

What caused these interminable conflicts? Most historians believe religion played a central role. The publication by Martin Luther in 1517 of his Disputation on the Power of Indulgences planted the seeds for the Protestant Reformation. This, in turn, led to the Counter-Reformation—also known as the Catholic Reformation—and the Inquisition. As Protestantism continued to expand into areas previously dominated by the Roman Church, imperial authority was destabilized, as were the boundaries of kingdoms. And war came.

When the belligerents met in Prague in the 1640s in an effort to end the fighting, they knew religion would continue to be a bone of contention unless it was squarely addressed. The solution, as set forth in the Treaty of Westphalia, granted the same rights to Lutherans and Calvinists as to Catholics in Germany.[2]

The Peace of Münster, in turn, while securing the primacy of the Dutch Reformed Church in the provinces, provided for private worship and liberty of conscience for all faiths and allowed religious minorities to freely emigrate. For the Dutch, this was not a hard sell, given their long persecution by Catholic Spain.

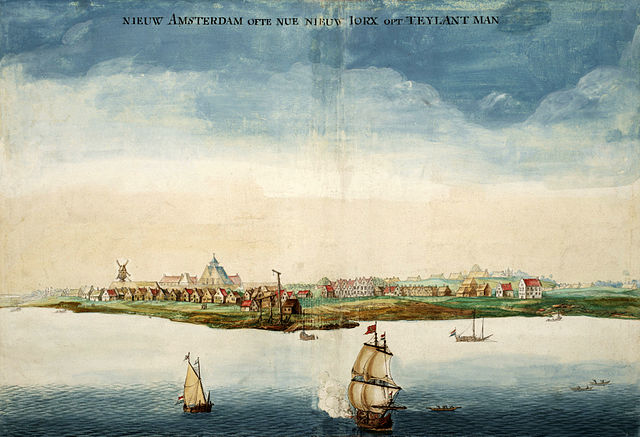

Peter Stuyvesant, the governor of the colony of New Amsterdam (known today as New York), however, apparently did not get the memo. He fervently believed the Dutch Reformed Church was the one and only true religion and he was not about to allow “secularists” to corrupt his colony.[3] When two-dozen Sephardic Jews fleeing the Portuguese Inquisition sought refuge in Stuyvesant’s colony in 1654, the governor seized their belongings and attempted to evict them from the city.[4]

He justified his proposed expulsion of the Jews to his superiors in the Dutch West India Company by claiming that Hebrews should “not be allowed to further infect and trouble this new colony” since they are “hateful enemies and blasphemers of Christ.”[5] But the Jews had written a letter of their own in which they reminded the colony’s backers not only of Holland’s embrace of religious tolerance but of the significant number of Jewish shareholders in the Company. Not surprisingly, the Company’s directors backed the Jews and allowed them to remain.[6]

Stuyvesant, however, was not deterred. He periodically arrested Lutherans and continued to harass Jews. But he reserved his supreme wrath for the Religious Society of Friends, better known as the Quakers. In April 1657 he arrested and expelled two Quaker women who were preaching in the streets of New Amsterdam. And a few months later he meted out far more severe punishment to Robert Hodgson, a Quaker who was winning converts on Long Island.

Stuyvesant had him arrested but “magnanimously” allowed him to choose between two punishments: (1) a hundred-guilder fine (more than the cost of Manhattan), or (2) two years on a work gang. Hodgson declined to accept either, whereupon Stuyvesant had him whipped several consecutive days.[7] Finally, he was released and expelled from New Amsterdam.

To stem the tide of Quaker immigrants, Stuyvesant issued a new edict: “No Quakers Allowed.” Any ship bearing practitioners of that faith would be seized and anyone caught giving them quarter would be fined.

Stuyvesant anticipated no push back from the Company’s directors since none of them were Quakers. On this score he was correct. Nevertheless, he was rebuked, albeit from an unexpected direction. Thirty citizens of Flushing (today, a neighborhood in the borough of Queens) sent him a “remonstrance”—known today as the “Flushing Remonstrance”—which was a quasi-legal document wherein grievances are set forth and redress requested.

While such petitions were not unusual, this one was striking in two respects.[8] First, not one of the petitioners was a Quaker. While all those who previously challenged Stuyvesant’s religious intolerance were members of the religion being persecuted, these men were not. They were not speaking for themselves but for a principle.

Second, while the authors of the Flushing Remonstrance advanced several reasons why they objected to Stuyvesant’s treatment of Quakers, they began with the most important one: they were inspired by God to speak up and dared not ignore his promptings. “The Lord hath taught … the civil power to give an outward liberty in the state,” and “love, peace and liberty…[should be extended] to Jews, Turks and Egyptians.”[9]

Stuyvesant was not amused. He came down hard on the Flushing ringleaders, levying draconian fines and issuing prison sentences of indeterminate length. With no legal recourse or rights of appeal, they eventually cracked, recanting their petition for redress.

But Quaker missionary zeal could not be contained. Four years later they were back in Manhattan, and this time Stuyvesant’s policy of discrimination was countermanded by the Company’s directors. While they shared his distaste for these “sectarians,” continuing to exclude them could diminish the population and discourage immigration, “which must be favored at a so tender stage.”[10] Thus, Stuyvesant was instructed to “allow everyone to have his own belief” so long as they gave no offense to their neighbors.

The Dutch West India Company had expanded the 17th-century notion of religious tolerance, albeit for commercial reasons. Genuine religious tolerance, they realized, is something more than a state-approved religion granting a privilege to religious minorities out of the goodness of its heart. When properly practiced and understood, it can exhibit a “more positive attitude of permitting differences as a source of benefit for all.”[11]

In the late 18th century, James Madison identified yet another benefit of pluralism: many sects help guarantee religious liberty. When “society itself [is] broken into so many parts, interests, and classes of citizens…the rights of individuals or of the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority.”[12] But might there be other benefits of religious liberty, ones that could make each faith tradition better and stronger? The Scottish poet, Robert Burns thought so.

While attending church one Sunday he spotted a louse on the bonnet of a lady, which inspired him to write a playful, yet insightful, poem: “To a Louse, On Seeing One on a Lady’s Bonnet, at Church 1786.” It is playful in the sense that it is addressed to the louse with great indignation. “How dare you mar the beauty of this fine lady’s bonnet!” But it concludes with these meditations:

O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us

To see oursels as others see us!

It wad frae many a blunder free us,

And foolish notion:

What airs in dres an’ gait wad lea’e us,

An’ evn’ devotion![13]

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we had the power to see ourselves through the eyes of others, he muses? Might not we be moved to rethink some of our opinions and abandon our pretenses, and, in the process, improve our religious devotions? As noted by Jack Miles, the General Editor of The Norton Anthology of World Religions, “So many of the cruelest mistakes in religion are made not out of malice but out of simple ignorance, blunders we would willing avoid could we but see ourselves as others see us.”[14] Sadly, the ignorance of which he speaks is, more often than not, a product of chauvinistic pride and arrogance, Peter Stuyvesant being a prime example.

While we cannot see ourselves through the eyes of others, we can take a step back from our faith and reappraise those parts of our religious tradition that are of dubious provenance or a source of discomfort to others and ourselves. Are we carrying some excess baggage that is holding us back spiritually and impeding our growth, both as individuals and as a church?

Perhaps by learning and borrowing from other faiths—adding their truths to our own—we can, in the words of the Apostle Paul, find “a more excellent way”[15] and thereby forestall future mistakes and blunders. Doing this properly, however, will require us to focus on “the bonnet and not just the louse” when we look at other religions and “to see the louse as well as the bonnet” as we reexamine our own.[16]

Virtus state in medio, reads the Latin proverb. “Virtue stands in the middle.” And the middle is where humility can be found.

[1] Norman Davies, Europe: A History (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 565-568.

[2] Ibid, p. 565.

[3] Richard Brookhiser, Give Me Liberty: A History of America’s Exceptional Ideal, (New York, New York: Basic Books, 2019), p. 32.

[4] Peter Manseau, Objects of Devotion: Religion in Early America, (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2017), p. 91.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Give Me Liberty, p. 35.

[8] Ibid, p. 36.

[9] Ibid, p. 37.

[10] Ibid, p. 45.

[11] Mark Greengrass, “Religious or Secular? The Edict of Nantes, Formation and State Formation in Late Sixteenth-century France,” in Ruth Whelan and Carol Baxter, eds., Toleration and Religious Identity: The Edict of Nantes and Its Implications in France, Britain, and Ireland, (Dublin, Ireland: Four Courts Press, 2003), p. 126.

[12] James Madison, Madison: Writings, (New York, New York: Library of America, 1999), p. 297 (The Federalist No. 51).

[13] Robert Burns, Collected Poems of Robert Burns, (Knoxville, Tennessee: Wordsworth Editions, Ltc., 1998), p. 138.

[14] Jack Miles, Religion As We Know It: An Origin Story, (New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2015), p. 3.

[15] 1 Corinthians 12:31 (ESV).

[16] Religion As We Know It, p. 5.

Very interesting post. Thanks for your never ending scholarship research and critical thinking and thanks for sharing the results with those of us who are lesser mortals.

You are quite welcome, Karen, though I must quibble with you on one point. From my perspective, you are the superior mortal, for Dick and you have taught me more things of eternal value over the years than you will ever learn from me.