In the early 1950s, the Karnaphuli pulp and paper mill, one of the earliest large-scale industrial enterprises in the recently established country of Pakistan, commenced operations. For raw material, the plant drew almost exclusively upon the vast bamboo forests along the upper reaches of the Karnaphuli River in East Pakistan. The suppliers of the bamboo and residents of the region, in addition to the venture’s founders, had high hopes for the project.

During the start-up phase, the business had its fair share of managerial difficulties and other troubles, but by the end of the decade it had begun to prosper. Then disaster struck. The bamboo began to flower.

To the uninitiated, the flowering of a plant would be viewed as either harmless or an indication that the plant was in good health. But for many species of bamboo, it is literally the kiss of death. Which was the case in Pakistan. Further, the blossoming, when it occurs, is not confined to a particular region. To the contrary, all plants of the same stock of bamboo will bloom at the same time, and then die. No matter where they are in the world.

No one could remember the last time the bamboo had blossomed in the region; it had been well over 50 years. The state of agricultural knowledge at the time made it impossible to predict when this would happen or how often. What made matters worse was that no one knew that flowering bamboo would be unusable for pulping. It actually disintegrated after it floated down river to the paper mill. And, as if that weren’t enough, the owners and investors were told it would take several years before new bamboo shoots would grow sufficiently for commercial exploitation.

The enterprise had two choices, neither of which was attractive: (1) close its doors and take a loss, or (2) find substitute raw materials. Quantifying the cost of the first option was easy, but no one knew how difficult or expensive the second one would be, meaning that investors might end up throwing good money after bad. Nevertheless, the decision was made to look for new sources of supply.

Initially, pulp was imported, but this was expensive and not a viable long-term solution. But then more creative ideas began to emerge. A different species of bamboo that had not flowered was collected in local villages, and other types of lumber proved to be good substitutes. Most importantly, research began to find other fast growing—and more reliable—species of pulp-producing crops that might at least partially replace the unpredictable bamboo. These measures, along with others, eventually succeeded and the project returned to profitability.

There is nothing particularly remarkable about this story. Businesses periodically confront major crises for which they are not prepared. Some are attributable to poor planning and bad management, while others are the result of unforeseen circumstances (e.g., a pandemic). Regardless, they either find a way to survive or they don’t. And whether they succeed or fail may have as much to do with circumstances beyond their control—including sheer luck—as with their efforts to save them. So, what can really be learned from these stories?

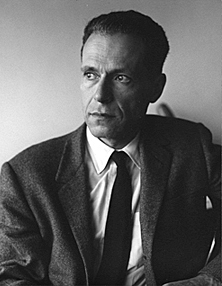

Around forty years ago, a brilliant economic philosopher by the name of Albert O. Hirschman, saw something at work here others had missed, yielding two remarkable insights.[1]

First, if investors and planners had known in advance all the difficulties the paper mill would encounter, they likely would not have pursued it. Simply stated, they would have doubted their ability to find solutions to problems of such magnitude.

Second, in many, though not all of these cases, foreknowledge of these huge obstacles and the resulting decision not to undertake the initiative would have been unfortunate, since, had the project been pursued, the resulting search for solutions would have set in motion a series of unintended—but hugely beneficial—consequences, not just for the enterprise and its owners, but for the community and its residents as well.

From these premises Hirschman articulated a principle of action, which he called “The Hiding Hand” (a play off of Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand”):

Creativity always comes as a surprise to us; therefore we can never count on it and we dare not believe in it until it has happened. In other words, we would not consciously engage upon tasks whose success clearly requires that creativity be forthcoming. Hence, the only way in which we can bring our creative resources fully into play is by misjudging the nature of the task, by presenting it to ourselves as more routine, simple, undemanding of genuine creativity than it will turn out to be.

Stated differently, since we tend to underestimate our ability to find creative solutions to difficult problems, it is fortunate that we are also inclined to underestimate the challenges posed by a new endeavor. These two offsetting miscalculations trick us into taking on challenges we would otherwise avoid.

According to The Hiding Hand principle, people frequently understate the risks attendant to a new task for any number of reasons, such as excessive optimism or contingencies they failed to envision. So, when the unexpected does occur, the rate at which people are required to engage in problem-solving suddenly accelerates: “they take up problems they think they can solve, find them more difficult than expected, but then being stuck with them, attack willy-nilly the unsuspected difficulties—and sometimes even succeed.”[2]

From these observations, Hirschman concluded that, when valuing a company, we should not only take into account its growth prospects, earnings history and market share, but should also accord a higher ranking to a venture which has gone through “considerable teething trouble” as a result of the intervention of The Hiding Hand. It may, as a result, possess greater resilience, flexibility and creativity than its competitors.

But he doesn’t stop there. Instead, he offers a most unexpected and thought provoking observation, though it is one he does not explore further:

We have ended up here with an economic argument strikingly paralleling Christianity’s oft expressed preference for the repentant sinner over the righteous man who never strays from the path.

The connection Hirschman made can only be properly understood if we fully grasp what Jesus meant when he said: “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick; I have come not to call the righteous, but sinners.”[3]

Christ was not saying there are righteous individuals who have never strayed from the path. Rather, what Jesus is saying—and I believe Hirschman understood this—is that because the self-righteous declined to acknowledge their need for repentance and believed, instead, that ritual purification guaranteed their salvation, they did not have “ears to hear” his message.

The impoverished, the infirm and the self-confessed sinner, by contrast, all had something in common: they found themselves facing seemingly insurmountable obstacles—caused either by serious mistakes they had made, contingencies they had not anticipated, or circumstances beyond their control—and they needed help. In Christ they found hope. But, to their dismay, he often gave them something different than what they were originally seeking.

He offered no simple solutions, and the only enemies he could empower them to vanquish were their own demons. Further, he had no handbook of instructions to distribute, and eschewed the very idea of a “checklist gospel.” He told them to love their neighbors, but didn’t tell them how, beyond caring for the poor and afflicted. And while he loved all with equal measure and made genuine seekers feel welcome, he never, ever promised a “safe space” where people would be shielded from disquieting ideas.

To the contrary, he wanted to make his disciples uncomfortable. His goal was to get them to rethink their most cherished beliefs and use their creative powers to devise solutions to the problems they and their communities confronted. Then and only then could they be reborn and begin their lives anew. And once they had passed through the refiner’s fire, they, like a business venture that has survived a major crisis, would find themselves endowed with unexpected strength and durability—and humility.

Perhaps the primary purpose of the veil of forgetfulness was not to erase the memories of our pre-mortal existence but to deny us foreknowledge of how challenging it would be to overcome our weaknesses, find our way in the world, and make peace with our fellowman and ourselves. But—building on Hirschman’s ideas—having cast our lot, we are compelled to use our creative resources to “attack willy-nilly the unsuspected difficulties.”

And yet, maybe The Hiding Hand principle does not always apply. Are there not times when we know the path forward will be fraught with peril and littered with unforeseen obstacles, and yet we nevertheless make a conscious decision to proceed?

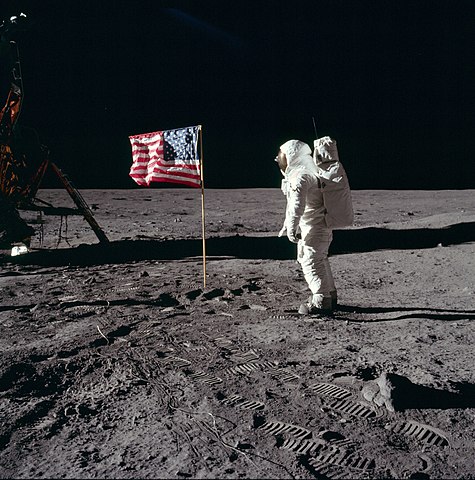

In 1962, when I was nine years old, President John F. Kennedy gave a speech at Rice University I will never forget. He spoke about the nation’s commitment to space exploration and his vision for the future. And to those who questioned the wisdom of sending a man to the moon, who feared the risks and thought the cost would be prohibitive, he offered the following rebuttal:

We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.

“John F. Kennedy Moon Speech – Rice Stadium”. NASA. Retrieved Sept. 5, 2020.

“Not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

Kennedy saw “new hopes for knowledge and peace” in the stars. And at the conclusion of his remarks, he asked for “God’s blessing on the most hazardous and dangerous and greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked.”

We need a similar blessing today, but it will only be bestowed if we stop asking for the “easy” and embrace the “hard.” For the “easy” has never served “to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills.”

[1] Albert O. Hirschman, “The principle of the hiding hand,” 10, No. 2, National Affairs, 10-23 (Winter 1967).

[2] Ibid, 13.

[3] Mark 2:17 (NRSV).

Great article. I still get goosebumps reading Kennedy’s challenge. I am sure you know this, but the United State’s total experience in space when he issued the challenge was about fifteen minutes: Alan Shepherd’s sub-orbital flight. A good (if sometimes harrowing because of the recounting of combat experiences) book I recently read that fits your theme: Deliberate Discomfort, How U.S. Special Operations Forces Overcome Fear and Dare to Win by Getting Comfortable Being Uncomfortable, by Jason B.A. Van Camp. Keep the articles coming!

Great post. Accepting life’s challenges for good and growth is always very difficult for those of us who are lazy enough to try to always choose the easier path and to see doom and difficulty as the enemy to be avoided whenever possible, rather than overcome. Life teaches us that often the choice to turn from challenges and hardships is not in our hands, the only choice we have is how we will react. As my dad always said “only you can create your own happiness.” It is all about how you choose to react. Don’t give others the power to determine how you feel or who you are. That is your choice. I love hearing about Hirschman. What an insightful man! President Kennedy was my first political inspiration. I was vice-president of the U of U Young Democrats when he was running for office and worked in his campaign. I was even invited to one of the inaugural balls but, of course, didn’t attend. Shortly after Dick and I met he took a job as the field rep in the Nixon campaign. He had a large car top sign on his can and I always wanted to shout out the window “not me.” I thought this would all be a big problem in our marriage but we were too busy with life and children and applying the “Hiding Hand” principal to think much about it. Your insights applying these ideas to Christ and his teaching are also revelatory. Thanks again.

Maybe your best yet, Eric. And Karen’s remark illustrates your point that perhaps we would not undertake life’s challenges if we understood what they might entail. Witness her half century creative adaption to being married to me; our 53rd anniversary is tomorrow.

Thorpe, I feel the same way about Kennedy’s speech at Rice University. I was glad I was able to find a way to integrate it in this essay, though it did not occur to me to do so until I was halfway through the first draft.

And thanks for the book recommendation. I will add it to the stack on my nightstand.

I’ll return the favor by suggesting you read “Rocket Men,” by Robert Kurson. It is about NASA’s decision to accelerate the Apollo 8 mission, which was the first to send men to the moon (though they simply orbited it 10 times and then came home).

The launch date was moved up by several months because the government believed the Russians were about to attempt the same thing (as it turns out, the intelligence community got it wrong). It was an insanely wreckless decision, in my opinion, because of the risks involved. If it had ended in tragedy, that would have been the end of the Apollo program. People were still reeling from the accidental death of the Apollo 1 crew. But they pulled it off. Even though you know the outcome, the story is intense.

And speaking of the Russians and the space race, you should check out, if you haven’t already, a new series on Apple TV+ called “For All Mankind.” It’s an alternate history where the Soviet Union succeeds in being the first to land a man on the moon. It’s pretty good.

Thank you for your kind words, Karen, and for sharing your thoughts about your experience with the Kennedy campaign. Those were indeed exciting times. And as we both know today, they were about to get a whole lot more exciting—and tragically contentious.

As to finding happiness, I always try to remember what Benjamin Franklin said about the single occasion where that word appears in the Constitution: “The U.S. Constitution doesn’t guarantee happiness; only the pursuit of it. You have to catch up with it yourself.”

Thanks, Dick. I wasn’t particularly pleased with the last one (“Vulcan”), so I tried to put a bit more thought into this one.

And congratulations on the 53rd wedding anniversary. It is quite an accomplishment to not only stay together that long but to live to see it!

Is it terrible that the first thing this Hirschman’s quotes made me think of were marriage and children? If I had truly understood the difficulties and hardships at the outset, I may not have embarked on this journey of family making. Being a celibate nun in a monastery has its appeal some days, to be sure. But I’m glad I was blind enough and optimistic enough to move forward. It certainly has required creativity and energy I didn’t know I had, but I am better for it a hundred fold and am grateful for the blessings it has brought. One of my other trusted mantra’s is “It will all work out. And if not, I will figure it. And if not, I’ll reach out to someone else who can.” I’m always surprised how true this is.

Wonderful writing. I read aloud several paragraphs while on a walk this weekend w/ B. It made for great discussion. Thank you for sharing, as always!

Thanks for your insights and kind words, S Barnhart.

I, too, have, on occasion, underestimated the complexity of challenges I have accepted, leading me to say to myself (to quote Laurel & Hardy), “Well, this is another fine mess you’ve gotten us into.” But I’ve learned that people (myself included), when confronted with an unexpected problem, tend to imagine the worst possible outcome, which, in reality, rarely occurs.

Also, while procrastination is not a good thing, it is surprising how often the passage of time will reveal a solution to a problem or produce circumstances that render it moot. Sometimes patience is not an option so, as you say, you have to find a way to move forward. But if it is, it is generally preferable to making a hasty decision.