Rituals, offerings and supplications on behalf of the dead are hallmarks of many faiths. Followers of the ancient Persian prophet Zoroaster chant prayers for the deceased in their funeral ceremonies, beseeching God to forgive their transgressions. The Catholic Church—until the Reformation quashed the practice—offered intercessory prayers and elaborate masses for the departed.[1]

The Old Testament, on the other hand, expressly enjoins all offerings to the dead.[2] Further, the general thrust of the New Testament and early Christian writings is that all such practices are futile since “death is a boundary beyond which salvation may not be procured.”[3] There are exceptions, however, such as this cryptic passage from 1 Corinthians: “Else what shall they do which are baptized for the dead, if the dead rise not at all? why are they then baptized for the dead?”[4]

More than 50 different interpretations of this passage have been advanced over the years.[5] And while no consensus has been reached as to its meaning, most scholars agree on the following:

First, with the exception of this verse, the Bible is completely silent on the subject of baptism for the dead.

Second, Paul neither condemns nor endorses this practice, and he exhibits no concern about the fate of those who have not been baptized. Rather, he merely references it in order to rebut the denial of the resurrection of the dead by some Corinthians. The reality and importance of Christ’s resurrection and our own are the sole focus of this epistle.

Third, it seems clear that Paul is not talking about a universal practice in the early Christian communities. This is evident by the pronouns he uses: “Else what shall they do who are baptized for the dead…why are they then baptized for the dead?” If this were a standard Christian practice, we would expect him to say, “what will we do” or “why are we baptized.”[6] Both LDS and non-LDS scholars agree that Paul is probably talking about a practice engaged in by a discrete group of Corinthians, not the church as a whole.[7]

Fourth, as noted by Krister Stendahl in The Encyclopedia of Mormonism, there is no other historical evidence of the practice of baptism for the dead during New Testament times or in early Christian writings.[8] Further, early church historians, most notably Tertullian (ca. 180 A.D.), Ambrose, and Chrysostom, identified this practice as being confined to a minor segment of Christian sects, such as the Marcionites and the followers of Cerinthus, who were deemed heretical.[9] And there has been persistent theological resistance to this practice ever since.[10]

The Book of Mormon is also silent on the subject of baptism for the dead or even the broader doctrine of salvation for the dead. Indeed, as noted by BYU Professor Charles Harrell, “the Book of Mormon people were taught not to worry about those who die without having heard the gospel in this life since they are redeemed automatically through the Atonement.”[11]

This does not mean, however, that the Book of Mormon contains something less than “the fullness of the gospel.” To the contrary, it clearly sets forth the fundamental principles of the gospel, which, according to Joseph Smith are: “the testimony of the Apostles and Prophets, concerning Jesus Christ, that He died, was buried, and rose again the third day, and ascended into heaven.” As the prophet went on to say, “All other things which pertain to our religion are only appendages to it.”[12]

Among these “appendages” are proxy baptism, celestial marriage, the three degrees of glory, and the Word of Wisdom—to name just a few—none of which is referenced in the Book of Mormon. So maybe we should exercise caution before claiming that the modern practice of a given “appendage” has an antecedent in a prior dispensation or that a given ancient text validates a contemporary religious ritual. After all, certain things, according to Joseph, have been withheld from mankind and have only been revealed in this, “the dispensation of the fullness of times.”[13]

Even though it is impossible to say with absolute certainty what Paul was talking about in 1 Cor. 15:29, two theories have achieved a significant number of disciples. One postulates that “being baptized for the dead” refers to non-believers who, after the death of a close Christian friend or relative, decide to become Christians themselves so that they can be reunited with their comrades or family members in the final resurrection.[14]

The other hypothesis is that it was a limited form of proxy baptism, one performed for a short period of time by some Christians but only on behalf of those individuals who had accepted the gospel but had died before being baptized.[15] When Joseph Smith introduced the doctrine of vicarious baptism in 1840, he also endorsed the idea of limiting the availability of baptisms for the dead in a similar manner. In a letter he sent to the Quorum of the Twelve, he wrote: “the Saints have the privilege of being baptized for those of their relatives who are dead, whom they believe would have embraced the gospel, if they had been privileged with hearing it….”[16]

Paul’s reference to vicarious baptisms for the dead was only one of several catalysts that prompted Joseph to sanctify the practice. A vision received by Ann Edwards Booth, a British saint living in Manchester, in the spring of 1840, wherein she saw the spirits in “prison” being taught the gospel and then baptized, reached the ears of Brigham Young who likely shared it with the prophet.[17] And the death later that year of Seymour Brunson, a close personal friend and bodyguard of the prophet, caused him to reflect on the afterlife. At Brunson’s funeral he reportedly talked about the gospel being preached to the dead in the spirit world and spoke of baptism for the dead.

Interestingly, Joseph Smith was not the first of his era to reinstitute the practice of baptism for the dead by proxy. During the First Great Awakening in the mid 1700s, the Zionitic Brotherhood in Ephrata, Pennsylvania, introduced proxy baptisms, a practice that spread locally and survived until the 1840s.[18] Whether Joseph was aware of this community and their religious rituals is unknown. But clearly other people of faith were engaging in similar practices for the spiritual welfare of the departed.

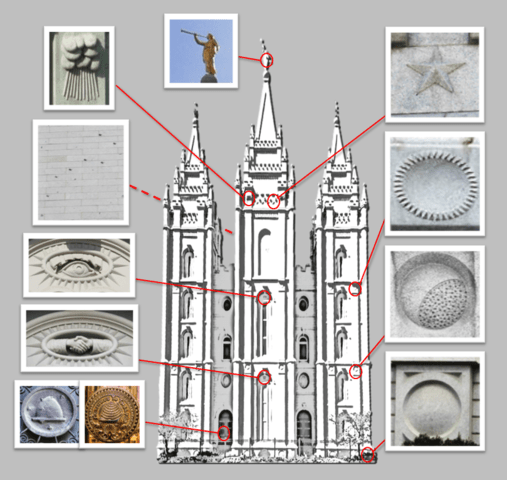

But this was only the beginning for the prophet. Eighteen months after he introduced proxy baptisms, he joined the Freemason Fraternity in Nauvoo.[19] The Masonic rituals and teachings he and several of his colleagues—including his brother Hyrum and Heber C. Kimball —embraced exerted considerable influence on the evolution of the endowment ceremony and other temple ordinances.[20] Joseph refined and expanded upon what he learned from Freemasonry, constructing a unique salvation and exaltation edifice, one he built on the foundation of proxy baptisms.

As much as I admire the prophet’s teachings and cosmology, I find it difficult to accept one thing he and his successors have taught about baptism for the dead and other vicarious temple rituals: that those who did not receive saving ordinances during their lifetimes are confined to some “spirit prison” until proxy ceremonies on earth are performed for them.[21]

Wilford Woodruff wondered how he would feel upon going to the spirit world and meeting his ancestors and discovering they are “shut up in prison” because he failed to do temple work for them.[22] I, on the other hand, wonder: “What kind of God would stand in the way of the post-mortal progression of one of his children simply because they had not participated in a religious ritual, either during their lifetime or via proxy?”

I find solace in Joseph’s vision in the Kirtland Temple where he saw his brother Alvin, along with Adam, Abraham and his parents, in the presence of God in the Celestial Kingdom and marveled how Alvin had obtained such an inheritance without having been baptized.[23] While that revelation does not, I suspect, diminish the importance to our ancestors of proxy temple ordinances, it does beg the question: “Are we—not our ancestors—the principal intended beneficiaries of temple work?”

When we engage in family history, we look back in time and, in the process, discover those who embraced the gospel before us, fought to protect the freedoms we enjoy, or made great sacrifices—many unheralded—for their families, friends and neighbors. We also frequently find ancestors from foreign lands or do proxy work for someone who lived centuries ago, individuals whose lives bears little resemblance to our own and yet are our equals, if not our superiors, in the eyes of God.

This fosters not only humility but also tolerance for those who are different from us, who do not share our beliefs, our culture, or our nationality. I believe our expansive vision of the family of man explains, in part, why our church and its members generously offer assistance to those in need, no matter their country of origin, race or religious persuasion, and encourages members and others to support refugees in their communities.

That vision can exert a positive influence on those around us—an influence sorely needed in a world increasing beset by divisions among, and confrontations between, people and nations. Perhaps this unanticipated benefit of temple work and family history is one of the reasons why proxy baptisms, sealings and marriages for all eternity were reserved for our time.

[1] MacGregor, Neil, Living with the Gods, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018), pp. 83-84.

[2] Deuteronomy 26:14. There is evidence, however, of rituals on behalf of the dead in late Judaism.

[3] Jeffrey A. Trumbower, Rescue for the Dead: The Posthumous Salvation of Non-Christians in Early Christianity, (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 33.

[4] 1 Corinthians 15:29 (KJV).

[5] Kevin L. Barney, “Baptized for the Dead,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship, (Vol. 39 2020), p. 117.

[6] Lending weight to this interpretation is the fact that Paul immediately reverts to writing in the first person in verses 30-32: “why stand we in jeopardy,” “I die daily,” etc.

[7] Barton, John and John Muddiman, Editors. The Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 1131; Charles R. Harrell, “This Is My Doctrine,” (Sandy, Utah: Greg Kofford Books, 2011), p. 355.

[8] Krister Stendahl, “Baptism for the Dead: Ancient Sources,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, Daniel H. Ludlow, ed., (New York, New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1992) Vol. 1, p. 97. See also John D. Reaume, “Another Look at 1 Corinthians 15:29, ‘Baptized for the Dead,’” Bibliotheca Sacra 152 (October-December, 1995), p. 458.

[9] The Marcionites performed this ordinance by having someone hide under the body of the deceased. When the corpse was asked by the officiant whether he wished to be baptized, the concealed individual would respond in the affirmative on the deceased’s behalf. Reaume, “Another Look at 1 Corinthians 15:29,” p. 457.

[10] Barney, “Baptized for the Dead,” pp. 104-105.

[11] This Is My Doctrine, p. 361

[12] Joseph Fielding Smith, compiler, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Company, 1977), p. 121.

[13] D&C 128:18.

[14] This position hinges on the meaning of the preposition “for” in v. 29, which is huper in the original Greek. Many scholars believe that, in this context, huper denotes the cause or reason of an action as in the sense: “because of,” or “on account of.” “Why are they then baptized because of the dead?” Paul frequently employs this usage in his other letters (e.g., Rom. 25:9: 2 Cor. 1:6; 2 Cor. 12:8; Thess. 1:5). John D. Reaume, in “Another Look at 1 Corinthians 15:29,” supra, makes a strong case for this position.

[15] N. T. Wright, Paul for Everyone: 1 Corinthians, (Louisville, Kentucky: West Minster John Knox Press, 2004) p. 217. See also Rescue for the Dead, pp. 35-36.

[16] “An Epistle of the Prophet to the Twelve,” History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Vol. IV (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Company, 1974), p. 231 (emphasis added).

[17] Johnny Stephenson and H. Michael Marquardt, “Origin of the Baptism for the Dead Doctrine,” The John Whitmer Historical Association Journal, No. 1 (Spring/Summer 2017), pp. 134-135.

[18] John L. Brooke, The Refiner’s Fire: The Making of Mormon Cosmology, 1644-1844, (New York, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 42-44.

[19] His brother, Hyrum, along with Heber C. Kimball and several other church leaders had members for quite some time.

[20] Michael W. Homer, Joseph’s Temples: The Dynamic Relationship Between Freemasonry and Mormonism, (Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, 2014), pp. 2, 4, 396.

[21] D&C 128:22 (“…redeem them out of their prison; for the prisoners shall go free.”)

[22] Wilford Woodruff, Teachings of Presidents of the Church, (Salt Lake City, Utah: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004), p. 192.

[23] D&C 137:5,6.