It is December 1847, and Brigham Young is throwing a temper tantrum in the company of the other members of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles. It has been three years since the murder of Joseph Smith, the first President of the Mormon Church, and Young believes it is high time the Quorum reconstitute the First Presidency with Young, to use his words, as “King” of the Quorum with the power to rule “perfectly untrammeled.”[1]

Unsurprisingly, several members of the Quorum of the Twelve have reservations about Young’s proposal. They prefer to govern the church together, collectively holding the keys of the kingdom, while permitting Young to act as the church’s spokesman.

Young will have none of it. And he is especially angry with two of his fellow apostles. “I shall never get any rest,” he vowed, “until I get in that [Salt Lake] Valley and Parley Pratt and John Taylor bow down & confess that they are not Brigham Young.”[2]

To buttress his own claim of prophetic superiority, he referenced a recent dream where a “personage” appeared in his mind and empowered him to contemplate the solar system. When such arguments did not sway the others, he often reacted by shouting, singing and hollering, thereby preventing those with opposing views from speaking. Ultimately, Young wore them down, primarily by highlighting his remarkable skills at orchestrating the migration of the Saints to Utah. Thus, the apostles acquiesced to the formation of a new First Presidency with Heber C. Kimball and Willard Richards as Brigham’s counselors.

Young’s desire for status and recognition has been emulated by his successors and other church officials. For example, current church president, Russell Nelson, while he was a Regional Representative of the church (what today is called an “Area Authority”), wrote a memoir in the late 1970s. While it was being readied for publication, he asked President Kimball if he would write a foreword for his book. The foreword, as it appeared under Kimball’s name, spoke of Nelson’s “perfect family,” “sweet spirituality, and “skill as a surgeon” and described him as “a great man.” But Kimball’s personal diary reveals that Nelson was the one who authored the foreword; Kimball merely reviewed and approved it at his request.[3]

Competition among ecclesiastical leaders is as old as Christianity itself. We are all familiar with the story of the dispute among Christ’s disciples “as to which of them should be the greatest.”[4] Indeed, according to the New Testament Come Follow Me manual, one of them—John—when composing his gospel justifiably laid claim to such exalted and exclusive status when he referred to himself multiple times as “the disciple whom Jesus loved.”[5]

Or did he?

Literalistic readings of the scriptures invariably are superficial and fail to discern the author’s message. This is especially true when it comes to the Gospel of John, which is a meticulously structured work that is far more symbolic and metaphorical than the synoptic gospels.

His account of Christ’s ministry is highly schematic. It consists primarily of: (1) seven “signs,” the last of which—the Raising of Lazarus—foreshadows his resurrection, and (2) seven “I am” discourses where Jesus forcefully lays claim to his role as the Messiah.

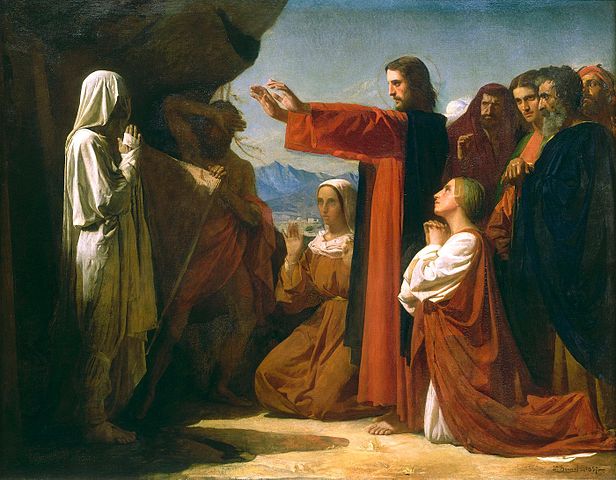

The Raising of Lazarus is crucial to the dramatic structure of John’s narrative. Situated at the midpoint of the evangelist’s gospel, it is the final and most extraordinary miracle—the seventh “sign”—performed by the Savior.[6] Further, this miracle, more than any other, was viewed by the Jewish aristocracy and their local Roman co-conspirators, as a mortal threat to the status quo, sealing Christ’s fate while simultaneously prefiguring his resurrection.[7]

The story opens with Lazarus’s siblings, Mary and Martha, sending word to Jesus from Bethany, a town just outside of Jerusalem, that their brother is seriously ill. Strangely, the Savior, who probably was in the Perean region, east of the Jordan River valley and about a day’s walk away, felt no urgency to depart; instead, he suggests that Lazarus is merely asleep. So he stays put for another two days before setting off for Bethany. He arrives a full four days after Lazarus has been entombed.[8]

It seems Christ deliberately wanted there to be no doubt regarding the man’s death before he arrived—a fact confirmed by the stench emitted by the decomposing corpse—so that no one would be able to question the reality of what he was about to do. Indeed, the odor was so strong that Martha didn’t want to remove the rock at the opening of the burial cave. But Jesus was not to be deterred: “Did I not tell you that if you believed, you would see the glory of God?”[9]

In accordance with the Savior’s command, the stone was removed, whereupon Jesus uttered the following prayer,“Father, I thank you for having heard me. I knew that you always hear me, but I have said this for the sake of the crowd standing here, so that they may believe that you sent me.”[10]

Christ then “cried with a loud voice, ‘Lazarus, come out!’” Within seconds, Lazarus exited the tomb, still bound, from head to toe, with strips of burial cloth. At which point Jesus says, “Unbind him, and let him go.”

The raising of Lazarus not only anticipates the Savior’s resurrection but also our own. Both the tomb of Jesus and that of Lazarus were sealed with a stone, and each man had been anointed and bound with strips of cloth. The reference to the burial cloth in each story is not a “throw-away” line. Rather, note what happens to the cloth in each story when the person in question is restored to life: Lazarus comes forth still bound in his burial linen to show that he has risen by another’s power and will die again. Jesus, on the other hand, leaves his grave clothes behind because he rises under his own power, and will have no more need of them.[11]

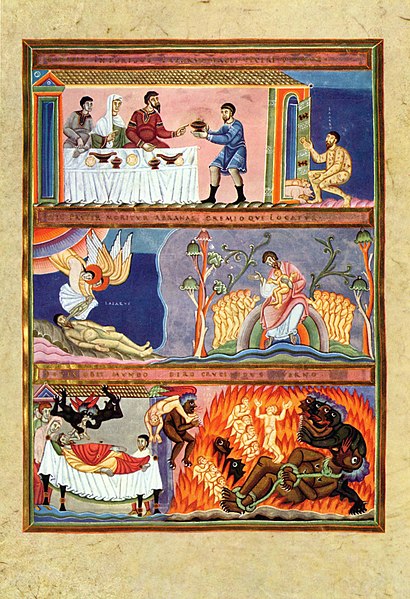

Though this story only appears in John, the evangelist’s decision to name his central character after the one used in Luke’s Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus is not coincidental. As you will recall, Lazarus was a poor beggar who survived off the crumbs from the Rich Man’s table and who derived meager comfort from dogs who licked his sores. When Lazarus died, he was carried away into Abraham’s bosom, while life after death was a series of never-ending torments for the Rich Man.

The rich man begs Father Abraham to send Lazarus to his five brothers “that he may warn them, so that they will not also come into this place of torment.” But Abraham refuses, saying, “They have Moses and the prophets and should listen to them.” The Rich Man doesn’t give up, persuasively arguing that it’s one thing to read the words of dead prophets; but the actual appearance of someone from beyond the grave is bound to get their attention.

Abraham, however, is unmoved. “[I]f they do not listen to Moses and the prophets,”—and here we see the connection with the Lazarus in John’s gospel— “neither will they be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.”[12]

Lazarus’s release by Jesus from the tomb proves the truth of Abraham’s words. The synagogue authorities, having just witnessed someone “rising from the dead,” remain unpersuaded. Indeed, while this miracle prompted many other Jews to join the ranks of the disciples,[13] it became the principal argument used by the Chief Priests to convince Pilate that Jesus must be stopped.[14]

What truly sets this story apart from the rest of John’s gospel, however, and allows us to solve our mystery as to the identity of the “beloved disciple,” is the unbridled affection exhibited by Jesus for the man he brought back to life and the anguish he experienced upon initially finding him dead.

The phrase “the disciple whom Jesus loved” or “the discipled beloved of Jesus” is used six times in the Gospel of John but nowhere else in the New Testament. And the first time it appears is immediately after the story of Raising Lazarus from the Dead.[15]

When Martha and Mary initially sent word to Jesus about Lazarus’s condition they said: “Lord, he whom you love is ill.”[16] Two verses later the evangelist writes: “Now Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus.” And when Jesus finally arrives in Bethany, he is so overcome by emotion at the loss of his friend that he is “greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved.”[17] He openly weeps—the original Greek text suggests he burst into tears—prompting some to observe: “See how he loved him.”[18] Thus, we are seemingly justified in concluding that Lazarus is the beloved disciple.

But wait—how can this be? Wasn’t the beloved disciple seated next to Christ, “leaning on his breast,” at the Last Supper? And doesn’t he also make an appearance, in the company of Mary, at the foot of the cross during the Savior’s crucifixion? What’s going on here?

The answer is both simple and intricate: Lazarus is the archetype for all who follow in our Savior’s footsteps, a symbol of those who respond to his teachings and are transformed. The beloved disciple is the one who undergoes the spiritual rebirth that Christ preached to Nicodemus.

A true disciple is someone who has eyes to see and ears to hear, who believes, and who understands. He strives to be close to the Savior (e.g., the Last Supper) and comforts those who have suffered a grievous loss (e.g., Mary at the foot of the cross). He is “a Lazarus” who has passed, in a spiritual sense, from death into life.[19] And it is this symbolic Lazarus to whom Christ alluded when he said:

Very truly, I tell you, the hour is coming, and is now here, when the dead will hear the voice of the Son of God, and those who hear will live. For just as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself; . . . .

John 5:25-26 (NSRV).

Because Lazarus listened to and embraced Jesus’ teachings during his lifetime, he was able to recognize his Savior’s voice while in the burial tomb. In a word, the “beloved disciple” is the personification of the disciple Christ wants each of us to be.

But all who aspire to such discipleship are imperfect and in need of repentance. In a very real sense, Martha and Mary’s initial message to Christ describes each of us: “Lord, he whom you love is ill.” In other words, we are all spiritually infirm.

Note, however, the evangelist’s choice of name—Lazarus—for the man who is sick: it is a form of the Hebrew name Eliezer, which means, “God helps.”[20] Just as it was only with God’s help that Lazarus was restored to life and became a symbol of the new creation, we likewise depend on our Heavenly Father’s assistance in order to experience the spiritual rebirth that will allow us to join the ranks of the “beloved disciples.”

Lastly, let us return to the episode where the disciples were bickering over who would be the most exalted in the Kingdom of Heaven. Surprisingly, Jesus doesn’t reprove them for behaving like children. Instead, he reminds them who they are and the manner in which he has led them during his earthly ministry:

The kings of the gentiles lord it over them, and those in authority over them are called benefactors. But not so with you; rather, the greatest among you must become like the youngest and the leader like one who serves. For who is greater, the one who is at the table or the one who serves? Is it not the one at the table? But I am among you as one who serves.

Luke 22:24-27 (NSRVUE).

One of the defining characteristics of Western culture is “ambition,” the desire to better one’s circumstances, to get ahead, to acquire wealth and do great things, both for oneself and others. The economic and political liberty we enjoy allow us, through hard work and the assistance of others, to realize our ambitions. Steve Jobs, for example, tenaciously pursued his dream of designing and building computers, smart phones and other devices that have helped others to achieve their goals and have facilitated significant breakthroughs in science and medicine.

Such striving, however, has no place in religion. The Greek word for ambition is philotimia, which literally means “love of honor.”[21] Christ gently chastised his disciples when they sought recognition and adulation in the Kingdom of God comparable to that bestowed on Caesar Augustus, the first Roman Emperor to be deified. I believe I am on solid ground when I say our Savior is not pleased when we seek honor, advancement and status in our church for the service we render. Our mission is to build His kingdom, not our own.

[1] John G. Turner, Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press, 2012), p. 172.

[2] November 16, 1847, General Church Minutes excerpted in: Gary J. Bergera, Conflict in the Quorum: Orson Pratt, Brigham Young, Joseph Smith, (Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 1994), pp. 54-61.

[3] Benjamin E. Park, “Newly released Spencer W. Kimball diaries shine a light behind the scenes of modern Mormonism,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 18, 2023, last accessed on February 25, 2023: https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2023/02/18/newly-released-spencer-w-kimball/

[4] Luke 22:24 (nsrv).

[5] “New Testament 2023: Come, Follow Me—For Individuals and Families, (Salt Lake City, Utah: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2022), p. 14

[6] Jeffrey John, The Meaning of the Miracles, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Erdmans Publishing Company, 2004), 217-218.

[7] John Shelby Spong, The Fourth Gospel: Tales of a Jewish Mystic, (New York, New York: HarperCollins, 2013), pp. 156-157.

[8] Ibid, p. 218.

[10] John 11:42-43 (nsrv).

[11] The Meaning of the Miracles, p. 219.

[12] Luke 16:29-31(nsrv, emphasis added).

[13] John 11:45 (nsrv).

[14] The Meaning of the Miracles, p. 218; The Fourth Gospel, pp. 159-160.

[15] John 11:1-44 (nsrv); The Fourth Gospel, p. 250.

[17] (John 11:33 (nsrv). “Deeply moved” hardly captures the meaning of the underlying Greek word, embrimaomai, which connotes “anger and snorting,” such as that exhibited by animals. Clinton E. Arnold, Gen. Ed., Zondervan Illustrated Bible: Backgrounds Commentary, Vol. 2, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2002), p. 111.

[18] John 11:36 (nsrv); Zondervan Illustrated Bible, p. 111.

[19] The Fourth Gospel, pp. 251-253

[20]), Ibid, p. 107.

[21] Barry Strauss, Masters of Command: Alexander, Hannibal, Caesar and the Genius of Leadership, (New York, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012), p. 19.

Interesting and full of fascinating insights. I enjoy and appreciate your pieces. You always give me a lot to ponder.

“The beloved disciple is the one who undergoes the spiritual rebirth that Christ preached to Nicodemus” and “… our Savior is not pleased when we seek honor, advancement and status in our church for the service we render. Our mission is to build His kingdom, not our own” jump out at me. Words to live by.

Karen & Tina,

Thank you both for your comments and for taking the time to read my stuff. I really appreciate it.