Mormons pride themselves on being “a temple-building” people. Yet we often miss, or fail to comprehend, numerous references to temples throughout the Old and New Testaments. Indeed, a compelling argument can be made that much of the Bible is one long meditation on the subject of sacred space. And it begins at the beginning.

Contrary to popular belief, the creation story in Genesis does not purport to explain the origins of the universe; nor is it a literal description of how our world came to be. Rather, it is an account of the transformation of the material cosmos, which had evolved over eons, into a place where God can interact with his children.

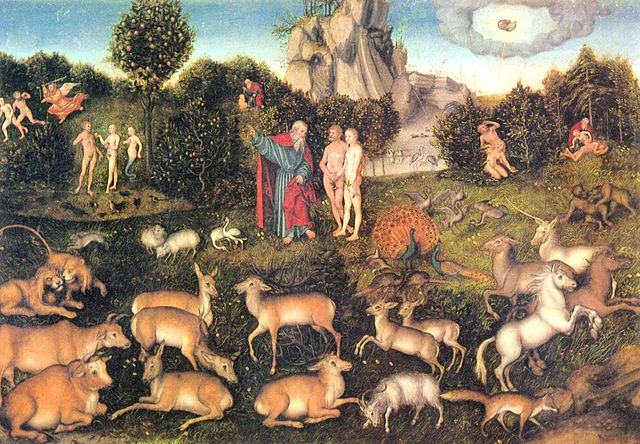

Jehovah is bringing order to the world with the specific objective of creating a sanctuary: a temple that will eventually encompass the entire earth.[1] Adam and Eve initially aid in this process—Adam names the animals and the Lord gives Adam and Eve dominion over all living things.[2] But it is only partially complete after seven days. At this juncture, the temple environs are limited to Eden, with the expectation that the couple, under the Lord’s guidance, will add many additions in the future. But God’s plan to expand his temple is abruptly put on hold when Adam and Eve transgress and are evicted from the Garden.

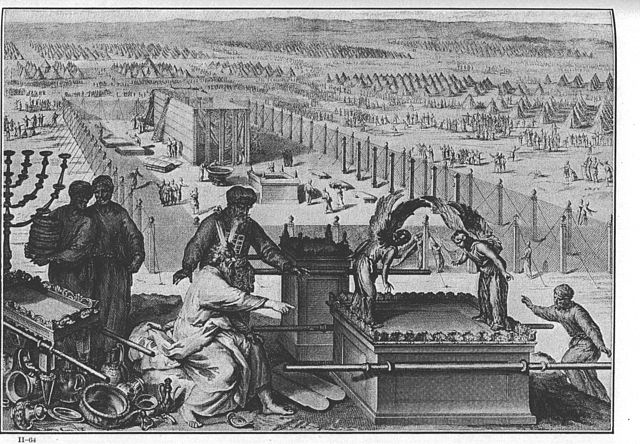

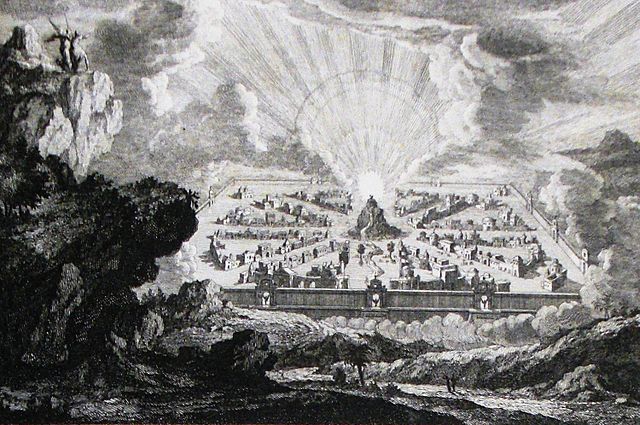

Jehovah’s first back-up plan was the Abrahamic covenant and the Israelites, who were to be his emissaries to the rest of the world. One of the first things they did, after escaping the clutches of the Pharaoh, was to create a new sanctuary where Jehovah could dwell among them in the wilderness.[3] This was accomplished with a “portable temple”—the Tabernacle—that in its design captures the visual imagery of the creation and the Garden.[4]

For example, the narrative describing the construction of the tabernacle is in seven segments. The sixth segment describes how the Spirit of God fills men to create the objects for the tabernacle while the seventh reminds Israel to keep the Sabbath day holy.[5] Further, the tabernacle, like the Garden of Eden, was where God is enthroned on the ark of the covenant.[6] It also included a six-branch seven-lamp menorah emblematic of the tree of life, and the law of Moses which represented the tree of knowledge.

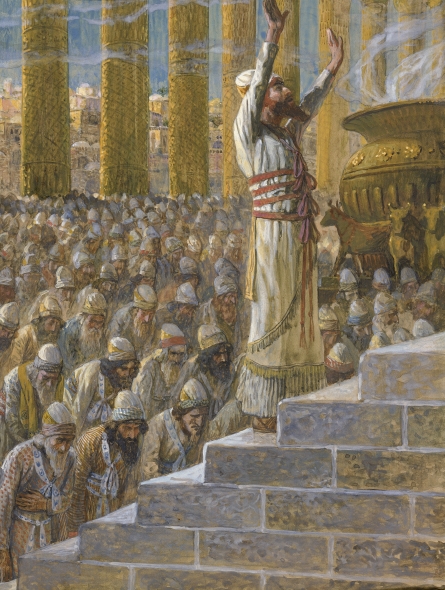

During the reign of Solomon, the Tabernacle was replaced with a temple, the construction of which was also patterned after the Israelites’ creation story. For example, Solomon took seven years to build the Temple and its dedication ceremony lasted seven days, which was followed by a seven-day feast.[7]

The seventh day was the climax of the creation account at which time God takes up residence in his new sanctuary (the Garden/temple). But, like Adam and Eve, the Israelites let him down. They fall into iniquity and are taken into captivity by the Persians, which leads to the desecration of Solomon’s temple.

During their exile, the Israelites sought to create “sacred space” of a different kind: they assembled, compiled and edited their records and recorded their oral traditions to create the Old Testament essentially as we know it today. This earned the Jews the nickname the “People of the Book,” and perhaps is one of the reasons why John the Evangelist refers to Jehovah as “the Word,” i.e., as the personification of the scriptures.

Upon their return to Jerusalem in the 6th Century B.C., the Israelites rebuilt the temple, which stood until its destruction by the Romans in 70 A.D. Because of the unrighteousness of the high priests and Herod, however, its spiritual destruction occurred well before then. Christ’s cleansing of the temple makes reference to this desecration but, enigmatically, he also talks about rebuilding it.

But where is this new temple? The answer to this question can be found in Christ’s response when, as he was evicting the moneychangers, he was asked for a sign to justify his actions: “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.”[8] The Father’s first back-up plan—the Israelites—did not succeed. His only begotten, resurrected son would be his new temple and an instrument for the salvation of mankind that would not fail.[9]

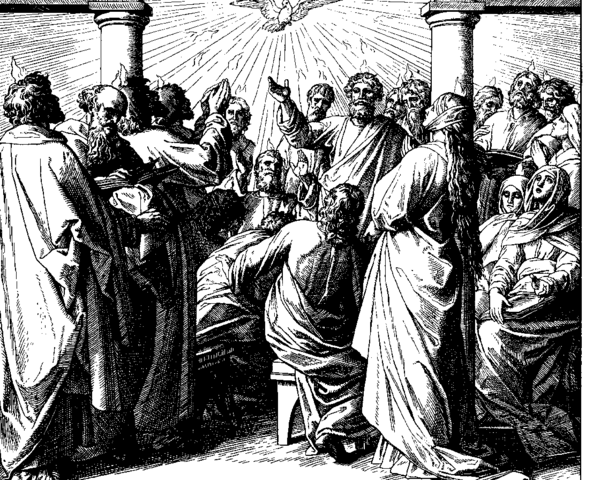

But was the temple in the form of Christ taken from the earth when he ascended to heaven? Not as far as the Apostle Paul was concerned. At Pentecost, the elements of the Tower of Babel are revisited, except this time the disorder of languages is resolved, as everyone can understand in their own language.[10] God, in the form of the Holy Ghost, has descended and taken up residence in a new sacred space—his disciples.[11]

Paul frequently employed a similar temple metaphor when corresponding with the saints in Corinth: “Know ye not that ye are the temple of God”? … [F]or the temple of God is holy, which temple ye are,”[12] and “[K]now ye not that your body is the temple of the Holy Ghost which is in you, …?”[13] Many Christian denominations, including Mormons, believe the apostle was referring to the individual physical bodies of the saints, but this is incorrect.

The reason for our misunderstanding of these passages lies in the pronouns—“you” (or “ye”) and “your”—Paul used, which do not translate well from biblical Greek into English. In the original Greek they are plural, but English does not have a recognized plural form for these words (unless you’re from the South, where they say “ya’all,” or Jersey, where they add an “s” to “you,” such as in, “Hey, yous guys. What ya doin’ over there?”) Those acquainted with one of the Romance languages—Spanish, French, Italian or Portuguese—will easily grasp this concept. In Spanish, for example, the word for “you” is usted and is used when speaking to one individual. But when addressing a group, the word becomes ustedes.

So, when Paul says “Know ye not that ye are the temple of God” or “… that your body is the temple of the Holy Ghost?” he is telling his listeners that all of them, collectively, constitute a single temple. In chapter 3 of 1st Corinthians, he employs this metaphor to stress the importance of unity because he has received reports of divisions within the ranks.[14] This was a chronic problem: he would preach to a particular community that was receptive to the gospel message, but the moment he left town the members start to argue over silly things, like whether it is okay to drink caffeinated beverages or if they must wear a white shirt to church.[15]

Paul consciously employed a temple metaphor when referring to the saints because he believed Christ was a “Second Adam” called to complete God’s original temple project.[16] Paul also understood that the spirit dwells in the group in a way that it does not reside in the individual. We are built together to become one whole structure, a single dwelling for his spirit.[17] As one religious scholar has noted: “I cannot worship God by myself.”[18]

Paul’s perspective is far from unique. In 1st Peter, the apostle employs similar imagery, calling believers “living stones” who are being built together into a spiritual house for a holy priesthood.[19] And John of Patmos concludes the New Testament in the Book of Revelations by expanding on this notion, revealing that the collective righteousness of God’s faithful children will allow Jehovah to accomplish his ultimate objective of restoring paradise and ushering in a new heaven and earth.[20]

The paradisiacal glory of our world, however, can only be achieved in my opinion if we read Malachi’s admonition (“… turn the hearts of the children…”) as being less about temple work—albeit a most important endeavor—and more about our sacred duty to attend to the needs of our children, siblings, parents and neighbors. The German author, director and screenwriter, Werner Herzog, once said: “Eternity depends on whether people are willing to take care of something.”[21] And nothing is more worthy of our care—or more essential to our salvation—than the welfare of our fellowman.

[1] John H. Walton, The Lost World of Adam and Eve: Genesis 2-3 and the Human Origins Debate, (Downers Grover, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, March 27, 2015), p. 51

[2] Genesis 1:28; 2:19-20.

[3] Exodus 25:8.

[4] Walton, The Lost World, p. 165.

[5] Exodus 25-27; 35-40.

[6] Wayne Grudem, Gen. Ed., ESV Study Bible, (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2016), p. 183.

[7] The Lost World, pp. 87-89.

[8] John 2:19.

[9] Nicholas Perrin, Jesus the Temple, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic Nov. 1, 2010), pp. 10-15; 105-107.

[10] Acts 2:6.

[11] Walton, The Lost World, p. 167. See also Ephesians 2:21-22: In him [Christ] the whole building is joined together and rises to become a holy temple in the Lord. And in him you [plural] too are be built together to become a dwelling in which God lives by his Spirit.”

[12] 1 Corinthians 3:16-17 (KJV)

[13] 1 Corinthians 6:19 (KJV)

[14] See 1 Corinthians 1:10.

[15] In chapter 6, Paul uses the body-temple analogy to illustrate the consequences of immorality. Although the offensive behavior in question involves the improper use by individuals of their bodies, his usage of plural pronouns reveals once again that his focus is on the spiritual impact of such behavior on the entire corpus of the church. E. Randolph Richards & Brandon J. O’ Brien, Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes: Removing Cultural Blunders to Better Understand the Bible, (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, Dec. 4, 2012), pp. 108-111.

[16] 1 Cor. 15:45.

[17] Misreading Scripture, p. 109.

[18] Rodney Reeves, Spirituality According to Paul: Imitating the Apostle of Christ (Downers Grove, Illinois: Intervarsity Press, 2011), p. 110.

[19] 1 Peter 2:5 (NASB)

[20] Revelation 21-22.

[21] Quoted in The Prague Sonata, by Bradford Morrow, (New York, New York: Atlantic Monthly Press Oct. 3, 2017), p. 341.