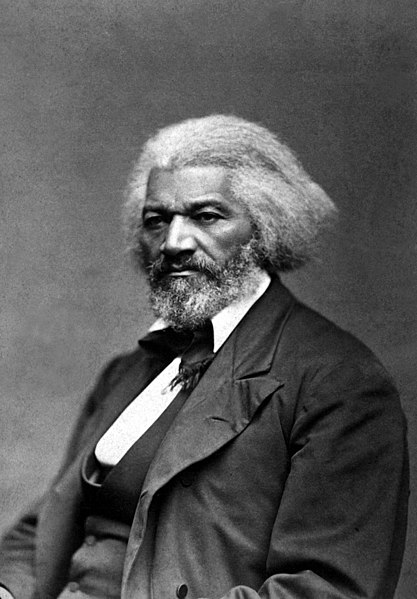

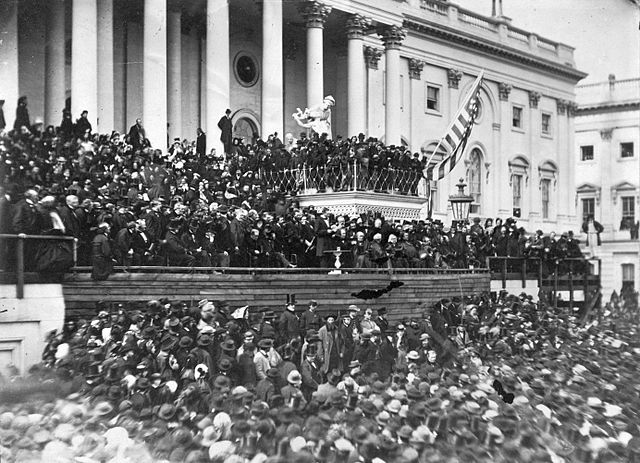

On the evening of March 4, 1865, a black man, dressed in his Sunday best, approached the entrance to the White House. He was there to see the President of the United States who, earlier that day, had delivered his second inaugural address to the nation. Having heard that Lincoln would be hosting a reception open to the public, Frederick Douglass decided to attend.

Douglass, until recently, had not been a big fan of Mr. Lincoln who, early in his presidency, seemed ambivalent on the question of abolishing slavery. But recent events—the single-mindedness with which Lincoln had prosecuted the war and his dogged efforts to win passage of a constitutional amendment banning involuntary servitude—had caused him to rethink his views.

Douglass had encouraged some of his friends to accompany him to the reception. But, without exception, they expressed fear that they would be turned away, ridiculed, and perhaps assaulted. As Douglass said, “they all with one accord began to make excuse”[1]—a reference to the Gospel of Luke’s description of Christ’s disciples who found reasons not to accompany the Lord during his final hours.

In the event, the forebodings of his mates were not entirely unfounded. The police standing guard at the President’s residence sought to deny Douglass admission. When he stood his ground, they employed subterfuge to keep him from the President, guiding him through the East Room and then out a window. Again he refused to yield, and with the assistance of a sympathetic congressman who witnessed the confrontation, Douglass at last secured a spot in the receiving line.

When his turn came, Lincoln openly declared: “Here comes my friend Douglass.” Clasping his hand enthusiastically and drawing him near, Lincoln said, “I am glad to see you. I saw you in the crowd today, listening to my inaugural address; how did you like it?”[2]

Douglass, mindful of the two and a half seconds allotted to each guest in the reception line, felt uncomfortable. “Mr. Lincoln, I must not detain you with my poor opinion, when there are thousands waiting to shake hands with you.”

“No, no,” Lincoln said, “you must stop a little, Douglass; there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours. I want to know what you think of it.”

Douglass replied, “Mr. Lincoln, that was a sacred effort.”[3]

A sacred effort, indeed.

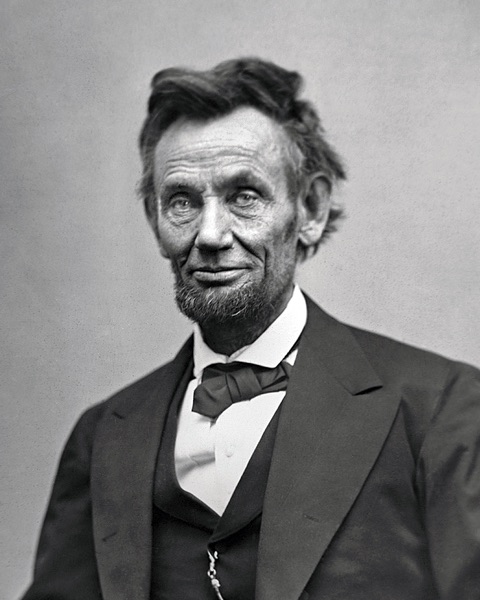

Lincoln’s Second Inaugural, though a mere seven hundred words, was a profound theological meditation on both the War Between the States, which was then drawing to a close, and the original sin for which the nation had been made to atone. It was replete with biblical quotations and scriptural allusions.

“Both parties deprecated war,” Lincoln observed, “but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish.” He paused briefly before describing, in passive voice, the inevitable result: “And the war came.”[4]

It was as if there was an external force, beyond the control of either party, that brought both sides to the point of no return. Ingenious compromises brokered in the past, they discovered, had only postponed the nation’s reckoning with its gravest mistake and allowed the coming whirlwind to grow with greater intensity.

Both North and South, according to Lincoln, “read the same Bible and, pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other.” But here, the President, with an obvious allusion to Adam’s condition upon being expelled from the Garden—having to work by the sweat of his brow to survive—condemned the Confederate States: “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces.” But he quickly added: “let us judge not that we be not judged.”

As noted by the author, Edward Achorn: “Just as Lincoln would refrain from celebrating the Union’s impending victory this day, he would claim no moral superiority.”[5] Instead, the President parted company with virtually every religious leader in the country by questioning the righteousness of both sides. Slavery was a great national failure requiring a joint confession. “The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes,” the President declared.

Coincidentally, Robert E. Lee, at the outset of the war, envisioned the horrible toll the coming conflagration was about to exact: “Both sides forget that we are all Americans. I foresee that our country will pass through a terrible ordeal, a necessary expiation, perhaps, of our national sins.”[6]

Lincoln unknowingly bore witness to the fulfillment of Lee’s prophecy, when he recited the following words from Matthew 18: “Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!” God had rendered judgment and passed sentence, one that all parties must accept because, as the President averred, quoting Psalms 19, “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

He then concludes by urging both sides to recognize that each had been wrong and the only way forward was to treat each other with mercy:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to know the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

His use of the word “charity” was an explicit reference to the teachings of Paul, who stressed the superiority of that virtue—the pure love of Christ—above all others. Lincoln also appears to have been inspired by one of the Savior’s final acts during his mortal life, one that was the capstone of his atoning sacrifice, which he performed while nailed to the cross. Looking to the heavens, he interceded on behalf of his and brothers and sisters, with the following simple plea: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” (Luke 23:34.)

It is noteworthy that Christ addressed his petition to his “Father,” not to “God.” As the 17th century Catholic theologian, Robert Bellarmine, taught, Jesus wanted him to exhibit the benevolence and compassion of a loving parent, not the severity of a judge. The Savior was fully cognizant of the divine wrath that had been aroused by those who had committed such enormous crimes and he wished to avert God’s anger.[7]

He implored the Father to forgive, both the imposition of the punishment and the crime itself. And he did this for two reasons. The first was to demonstrate his unconditional love for each of his brothers and sisters. The second was to teach us that just as his atoning sacrifice would not have been complete unless he forgave those who had wronged him, our faith, good works, and repentance will all be for naught unless we, too, forgive.

But who are we required to forgive? “them,” according to Jesus. Encompassed by that simple pronoun are the Romans, the High Priests, the Scribes and the Pharisees—and even the disciples who forsook him at the eleventh hour. Thus, we are to forgive the same people we are enjoined to love: all of our neighbors.

Jesus suggests that mercy is warranted in this instance because his enemies did not know they were persecuting unto death the Son of God. While Christ’s petition is remarkable for its compassion, it glosses over one unassailable fact: his adversaries would not have endured in this state of ignorance if their malice had not blinded them to the identity of this Holy Messenger.

Lincoln believed a similar spiritual blindness had brought his fellow countrymen to the brink of destruction. And he knew their sight could not be restored unless they first acknowledged their joint responsibility for slavery and the war it had wrought. Until they accepted their culpability and set aside their mutual enmity, each side would be incapable of seeing the mote in its own eye and the divine spark in that of the other. Then, and only then, would they be able to seek forgiveness from those whom they had abused and enslaved; and ultimately from the Lord.

There was, however, one man in attendance at Lincoln’s Second Inaugural who was unmoved by his words, who preferred vengeance over reconciliation. Five weeks later, on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, he fired a bullet into the skull of the 16th President of the United States.

Though a sinner like the rest of us, Abraham Lincoln, was nevertheless the savior of our country, a leader who gave his all that the ideals espoused in the Declaration of Independence might move closer to their full realization. He eschewed triumphalism and instead asked his fellow citizens, both North and South, to see the better angels of their nature. His final lesson to us all—one that he learned at the feet of Jesus the Christ—is that forgiveness is ordained of God.

[1] Edward Achorn, Every Drop of Blood, (Atlantic Monthly Press: New York: 2020), p. 267.

[2] Ibid, p. 269.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Abraham Lincoln, Speeches and Writings: 1859-1865, (Library of America: New York: 1989), p. 686.

[5] Ibid, p. 232.

[6] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (Oxford University Press: New York, Oxford: 1988), p. 281.

[7] Cardinal Bellarmine (Author), Brother Hermenegild (Editor), The Seven Words: Spoken by Christ on the Cross, (CreateSpace: Scotts Valley, California: 2013), p. 2.

Outstanding (again), Eric. How differently the country would have proceeded had John Wilkes Booth failed.

Thanks, Dick. Historians have often speculated on how reconstruction would have unfolded had Lincoln finished his second term. Though he undoubtedly would have done a better job than Johnson did, the task of reconstruction was a formidable one. And it’s uncertain whether Lincoln would have had public support for the aggressive policies required to transform the culture of the South and the racal attitudes of the North.

Thank you, Eric

Grateful you included this singular and significant event of the visit of Frederick Douglass. His story is worthy of telling in another separate treatise.

It is worth mentioning that in 1844, and small, obscure college came into existence in Michigan. It was known then and now as Hillsdale College, and one of their founding tenets, was to be “abolitionist”, and were ever faithful to the pledge. Subsequently, Frederick Douglass became a friend to the College, and spoke there at least once, and if one were to visit Hillsdale, a lovely memory was established in honor of Douglass in a very impressive statue, to inspire and stimulate students to ask and to think upon his life and legacy.

Some are still bitterly divided on Lincoln’s attitude toward slavery and the war itself, but I chose the better part, and honor him as you have done, especially the sanctifying principle of forgiveness.

May we all submit to Christ and this divine and key to salvation of forgiveness and further to “loving our enemy”

Good day, Eric

Michael

Great to hear from you, Michael.

The Abolitionist Movement in general, and Frederick Douglass, in particular, played an important role in concentrating public attention on the evils of slavery. But those today who accuse Lincoln of being slow to get on “abolitionist bandwagon” evince a lack of understanding regarding the politics of his era. Simply stated, they are guilty of presentism.

Going into the Republican convention in the spring of 1860, Lincoln had positioned himself as someone who opposed slavery—especially its expansion in the west—while simultaneously avoiding the more radical abolitionist positions that alienated moderate voters. This attribute, along with his exceptional oratorical skills, helped secure him his party’s nomination.

Lincoln understood the first and only rule of politics: you can’t change anything unless you get elected and it is impossible to get elected unless you get slightly more than half of the electorate to vote for you (or, in his case, slightly more than half of the Electoral College, since he only won 40% of the popular vote, though that was better than any of the other three candidates).

Once in office, Lincoln couldn’t suddenly take a more aggressive stance on slavery; otherwise, he would have alienated the border states, such as Maryland and Kentucky, which were crucial to the Union’s survival and its prosecution of the war. And there was also the matter of the Constitution, which protected slavery (a “legal technicality” Lincoln was able to sidestep later by treating the Emancipation Proclamation as a “wartime measure”). The abolitionists, by contrast, were a single-issue coalition, a luxury not afforded to Lincoln, who had a war to win and a country to hold together.

Lincoln had the vision to see a better America, one that truly embodied the principles of the Declaration of Independence, a document he often referred to as his “fountain of inspiration.” But he was only able to advance the cause of equality for all mankind because he was a clever, and sometimes ruthless, politician.

A great history lesson here in the middle of the reflections on forgiveness. thank you as always.

Absolutely outstanding post! So needed today. This could have been a great Conference talk. All members of the Church and all Americans need to hear something like this!

Karen Hammond,

I’m glad you enjoyed it. I find that history lessons teach us not only about those who came before, but also about ourselves. And sometimes the reflection we see in that mirror is not a pretty one.

Karen Hanneman,

Thank you for your kind words, as always. I was tempted, at the very end, to draw a parallel between Lincoln’s time and our own, but I figured most people could connect the dots on their own, if they were so inclined.

Eric

So True