The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there

— “The Go Between,” by L. P. Hartley

The crux of Christ’s mission and the core tenant of his gospel—his “good news” for mankind—was revealed on the day he was born. So, too, was an “alternative theology,” i.e., a different recipe for achieving peace on earth championed by a most formidable opponent.

“Now it happened that in those days an edict went out from Caesar Augustus that all the inhabited world should be enrolled in a census. * * * * And suddenly there appeared with the angel a throng of the heavenly army, praising God and saying, “Glory to God in the highest places and peace on earth among men of goodwill. Luke 2:1; 13-14. (D. B. Hart Translation).

The majority of biblical scholars believe there was no census mandated by Rome at the time of Christ’s birth.[1] Luke knew this. And so did his readers. This was simply a literary device, aka, a pretext, for introducing the villain of our story: Augustus.

Before we proceed, I feel the need to repeat something I’ve said many times before in these pages: the inhabitants of the ancient world were not like us. Their cultures, economies, governments, and customs bear little or no resemblance to our own (by “our own” I mean the western world). Most importantly for present purposes, the idea of accurate, cross-checked and documented history was foreign to them.

For the ancients “truth”—which we define almost exclusively in empirical terms—was communicated and understood in a variety of different ways: myth, literature, poetry, humor, propaganda, satire and yes, sometimes even history (e.g., the crucifixion and resurrection).[2] So, for us as students of the Bible, the first question we should always ask ourselves when analyzing an ancient text is, “What are we reading?” In the words of my dear friend Gonzo, “This one thing you must remember, or nothing that follows will seem wondrous.”[3]

* * * * * * * *

Augustus, born Gaius Octavius (63 bc, died in 14 ad), is best known as the first Emperor of Rome and the author of “Pax Romana,” an era of unprecedented peace he brought to Italy by ending a century of civil war. This brutal conflict ravaged not only Italy, but also Greece, Egypt, Spain, Anatolia, and northern Africa for almost 100 years, and only came to an end as the first century AD was beginning.[4]

For his efforts, he was hailed as “the savior of the whole world” and the greatest peacemaker known to man. And in 13-9 bc, just a few years before Christ’s birth, a great altar was erected to the peace brought about by Augustus. This Ara Pacis Augustae still stands in Rome today as a monument to the man’s ideals.[5]

A decree was also sent by Rome to all of its provinces mandating the adoption of September 23rd, the birthday of Augustus, as the first day of the New Year. The date of his birth was also celebrated on an inscription dated to 9 BC—a few years before Christ was born—in the ancient town Pirene (modern-day Bodrum, Turkey) grandiosely proclaiming: “The birthday of the god marked the beginning of the good news [aka, gospel] for the whole world.”

If you are confused by the phrase “birthday of the god [i.e., Augustus],” don’t be. Beginning with Julius Caesar, the Roman Senate began conducting religious ceremonies to deify worthy leaders shortly after they passed away. Kings in the Middle East at the time were also known to arrange for their deification during their lifetimes.[6]

In the classical world, the boundary separating the gods from mankind was not straight forward. For example, various heroes in Greek legends, such as Achilles, Perseus and Theseus, were thought to be half human and half divine. Nobody really believed a deified ruler was of a different nature from the rest of humanity. But divine status added to the majesty of their office and created a respectful distance between them and their subjects.[7]

Modern parallels can be found in several religions today. In the Catholic church, for example, the doctrine of papal infallibility, states that the Pope is preserved from error when he solemnly defines a doctrine of faith. Similarly, the prophet of the Mormon church a few years ago reminded all Latter-day Saints that “Prophets are rarely popular. But we will always teach the truth!” (Emphasis in the original.)[8]

* * * * * * * *

The deification of Caesar in 42 bc (two years after his assassination), was a turning point in the life of Octavius Augustus and helped solidify his grip on power. You see, he was the grandnephew and adopted son of Caesar and his sole heir, to whom Caesar bequeathed all his wealth—a fortune so immense it allowed him to finance legions of Roman soldiers.[9]

When a comet appeared in the skies over Rome in July 44 bc, during the funeral games for Julius Caesar sponsored by Octavian, it was hailed by the people as the soul of Caesar ascending to the gods, solidifying his deification. From that moment forward, Gaius Octavius “insisted on the being known as Caesar Divi Filius—the Son of God.”[10]

Now, the weird part.

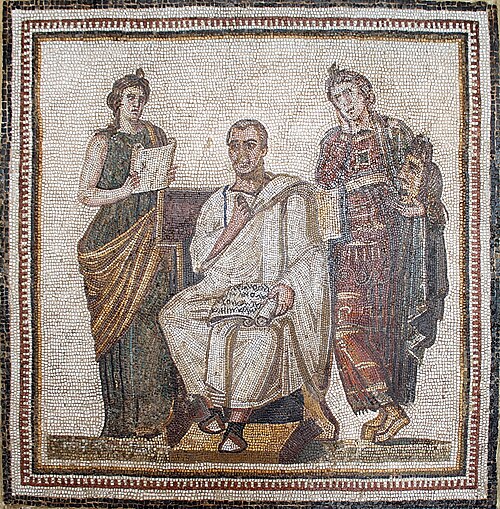

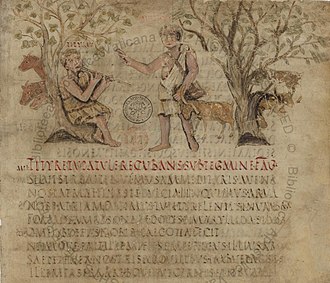

Publius Vergilius Maro (70 BC – 21 BC), known to us as Virgil or Vergil, was one of the greatest poets of the ancient Latin world. His most famous long-form poem is Aeneid, of course. But it is his Ecologues, a group of ten poems modeled on the pastoral poetry of Theocritus, to which I wish to call to your attention.[11]

This poem, composed in 40 BC, mentions a virgin and a divinely descended child before whom all the earth will tremble in homage in a golden age of peace when the remaining “traces of guilt” will disappear.[12]

It is not a stretch to suggest that Gentiles living in the Middle East and Asia Minor during the first century AD and who were familiar with Matthew and Luke’s Infancy Narratives, may have read this poem as a pagan prophecy of the Savior’s birth. It also seems to reflect indirectly a knowledge of some of the themes found in Isaiah 7–11.[13] But before you pick up the phone and say, “Hey, mom. Guess what I just learned!” please note: Virgil does not suggest that the Child was conceived by the Virgin.

Without getting further into weeds on this, suffice it to say that this poetic prophecy would have allowed both the followers of Augustus and the disciples of Christ to claim their man was the child of whom Virgil wrote.

* * * * * * * *

Augustus and his successors, in Luke’s telling, are Christ’s competition. And Luke appears to respond to the Augustus publicity campaign with his own proclamation: “Unto you this day is born in the city of David a Savior who is Messiah and Lord.”[14] In the words of the foremost student of the Infancy Narratives, Raymond Brown: “Men built an Altar to the pax Augustae, but a heavenly chorus proclaimed the Pax Christi.”[15]

The Pax Romana was certainly the greatest achievement of Octavian Augustus. But it was brought about by compulsion—literally, at the point of the sword. And he repeatedly found it necessary to unsheathe that weapon in order to keep the peace, which he did without hesitation. After all, the Latin verb pacare—which has the same root as pax—means “to pacify.’’ The Romans didn’t give damn how peace was attained. They just wanted everyone to behave and augment the wealth of Rome. [16]

Jesus offered a different approach: “peace on earth” but only “among men of good will.” This isn’t peace by force. Rather, it is peace grounded in the good will of mankind and is premised on three unambiguous rules:

1. Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, might, mind and strength.

2. Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.

3. Thou shalt love thine enemies and pray for those who persecute you.

The third of these precepts—loving your enemy—was revolutionary in Christ’s day. In the words of the biblical scholar, Amy-Jill Levine, “[Jesus] may be the only person in antiquity to give this instruction.”[17]

Unsurprisingly, the risks for those who venture to practice this precept are formidable. If you don’t believe me, just ask the Good Samaritan.

[To be continued]

[1] See, e.g., Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, pp. 412-418; 666-668; John Dominic Crossman, The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant, (New York, New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1992) p. 372 (“There never was a worldwide census under Caesar Augustus”).

[2] E. Randolph Richards and Brandon J. O’Brien, Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes, (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Books, 2012).

[3] Spoken by Gonzo, the narrator of the “Muppets Christmas Carol.”

[4] Adrian Goldsworthy, Pax Romana: War, Peace and Conquest in the Roman World, (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2016), pp. 12-13, 185; Brown, Birth of the Messiah, supra, p. 415.

[5] Raymond E. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament, (New York, New York: Doubleday, 1977) p, 59.

[6] Anthony Everitt, Augustus: The Life of Rome’s First Great Emperor, (New York, New York: Random House, 2006, p. 85.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Russell M. Nelson, “The Love and Laws of God,” devotional address delivered at Brigham Young University on September 17, 2019, last accessed on February 25, 2023: https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/russell-m-nelson/love-laws-god/ . Two years later, Nelson went further, stating that the teachings of all of the church’s General Authorities are pure truth. Russell M. Nelson, “Pure Truth, Pure Doctrine, and Pure Revelation,” October 2021 General Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, last accessed on February 25, 2023: https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2021/10/11nelson?lang=eng.

[9] Everitt, Augustus, p. 85.

[10] Tom Holland, Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the House of Caesar, (New York, New York: Doubleday, 2015) p. 42.

[11] Brown, The Birth of the Messiah, pp. 564.

[12] Ibid, p. 565.

[13] Ibid, p. 564.

[14] Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament, p. 59.

[15] Raymond Brown, An Adult Christ at Christmas, (Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 1978), p. 18.

[16] Goldsworthy, Pax Romana, pp. 13, 383. For a modern-day equivalent, the animosities between the various ethnic and religious groups in the Balkans—Muslims, Bosniaks, Roman Catholic Croats and the Eastern Orthodox Serbs—were kept in check during most of the 20th century by Yugoslavia’s strongman, Marshal Tito, and indirectly, in my opinion, by the Soviet Union. But one year after the U.S.S.R.’s disintegration, the external pressure for unity in the Baltics evaporated and the Furies escaped, engulfing the Balkans in war for most of the 1990s.”

[17] Amy-Jill Levine, Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables by a Controversial Rabbi, (New York, New York: HarperOne, 2014), p. 86.

Interesting, insightful, useful, and well worth reading and pondering.

You never disappoint me when I peruse your scholarship and thoughts.

Thank You & Merry Christmas

I really like the sophisticated use of history in this essay. A nice Christmas gift.

Many thanks, Karen and Doug, for taking the time to read this essay and share your thoughts with me and others. Much appreciated, as always.

Hi, Grandpa, I found this on my school computer, so while other kids are playing games during class, I can be learning from your wisdom.

There is a lot to digest here for me. I find it fascinating how God teaches us through parallels and contrasts: Augustus and Christ bringing peace but one through war and one through love. That is really powerful.

I also really liked this quote:

“For the ancients “truth”—which we define almost exclusively in empirical terms—was communicated and understood in a variety of different ways: myth, literature, poetry, humor, propaganda, satire and yes, sometimes even history…”

I was impressed recently in Sunday School that the teacher ventured to say that the story of Adam and Eve could be communicating truth through myth rather than it being a historical narrative!

As always, enjoy your thoughts. They are elevating!

Your Sunday School teacher is both enlightened and courageous, in my opinion, Stephanie. And I concur with his reading of Genesis 1 & 2.

The text itself refutes the proposition that Adam and Eve were the first humans on earth, e.g., Cain is exiled to the Land of Nod, marries and builds a city, undoubtedly with the assistance of others. Also, our own endowment ceremonies reinforce the mythical character of this story (“Each of you should view yourselves as Adam and Eve at the alter …,” i.e., Adam and Eve are mythical proxies for each one of us.)

It’s amazing the mysteries you can unearth when you stop reading our sacred texts through the eyes of a 21st century westerner.