[Author’s Note: This is the continuation of an essay I authored on December 25, 2025, called “An Adult Christ at Christmas,” a title I borrowed from a short treatise authored by the Catholic biblical scholar, Raymond Brown. I recommend you read that essay first (if you have not already done so) before reading this one.]

“Life is constant movement, and therefore goodness in life is not a certain state, but the direction of movement.”

Blaise Pascal, Pensées

“A text without a context is just a pretext for making it say anything one wants.”

Ben Witherington, III, Professor of New Testament Interpretation, Asbury Theological Seminary

The Parable of the Good Samaritan, as recorded by Luke the Evangelist, was delivered by Jesus during his final journey to Jerusalem. It is arguably the most well-known of Christ’s short stories. Lamentably, it is also the parable most prone to decontextualization, i.e., removing the story from its original context in order to advance an interpretation Christ never intended for the sole purpose of championing a parochial interest. This is especially true of allegorical readings of this text.[1]

To illustrate this point, I deliberately decontextualized this parable in the first sentence of the preceding paragraph by using the name by which it is commonly known. Never did the Savior use the phrase “good Samaritan” during his ministry. And for good reason.

What if the setting for this story were in a town in Samaria and Jesus flipped the script when delivering it to a group of Samaritans? Would we call it, The Parable of the “Good Jew?” Do you know who was fond of the term the “good/decent Jew”? Henrich Himmler. He employed it to discourage his SS officers, each of whom likely knew one or two “decent Jews,” from sympathizing with the “human animals”—the Jews, the Gypsies, the mentally ill, etc.— they were systematically liquidating.[2] (By the way, in case you’re wondering, the Samaritans are still with us).

Forgive my hyperbole. I’m simply trying to illustrate how the use of the term “good Samaritan” by Christ would not only be disrespectful to a group he was trying to win over; it is also a term his audience would have found jarring. It is just one of many ways, as noted by the biblical scholar Amy-Jill Levine, Christianity has tried to domesticate this parable, using it for purposes the evangelist never intended. So, let’s remember: this parable is a “first-century short story spoken by a Jew to other Jews.”[3]

* * * * * * * *

Jesus did not spontaneously deliver this story in sermon-like fashion to an audience. Rather, he did so in response to a series of questions posed to him by a lawyer who wanted to know what he needed to do to inherit eternal life.[4] Jesus responded with questions of his own: “In the Law, what is written? How do you read?”[5]

The lawyer was quick to answer—“You will love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind and your neighbor as yourself”—which the Savior said was correct. But our beloved attorney—whose real motive, I’m sorry to report as a fellow member of the bar, was to provoke a response he could use against Jesus—had a follow-up query: “And who is my neighbor?” Whereupon Christ responded with a story about a priest, a Levite, a Samaritan, a wounded man—presumed by virtually all biblical scholars to be a Jew[6]—and an Innkeeper.

This story is recorded in six verses. In the first, a man/Jew who was travelling from Jerusalem to Jericho was viciously attacked by thieves, stripped of all of his possessions (including his raiment), and left “half dead.” The next two passages chronicle the indifference of a priest and then a Levite, who took notice of the critically injured man but chose not to come to his aid. And so, continued on their way.

In the first century A.D., the temple in Jerusalem was served by three classes of people. In descending order, they were priests, Levites and laymen assistants. Some scholars believe the priest and Levite did not wish to risk defilement by coming to the aid of a man who may be dead. This would require them to return to Jerusalem and undergo a week-long process of purification. Other scholars, however dispute this interpretation. I personally believe Martin Luther King got it right when he said that the only relevant question in the mind of these two men was, “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?”

Christ’s audience knew a third passerby would follow the priest and the Levite. For the use of rhetorical trilogies was common in postexilic texts and is what would have been expected by a first-century Jewish audience.[7] But they thought it would be the aforementioned layman assistant who would save the day, putting to shame the priestly caste. So, the substitution of a Samaritan was shocking—precisely the reaction Jesus wanted. Now he had their attention.

33 But a Samaritan while traveling came upon him, and when he saw him he was moved with compassion.

34 He [the Samaritan] went to him and bandaged his wounds, having poured oil and wine on them. Then he put him on his own animal, brought him to an inn, and took care of him.

35 The next day he took out two denarii, gave them to the innkeeper, and said, “Take care of him; and when I come back, I will repay you whatever more you spend.”

Unlike the priest and the Levite, the only relevant question in the mind of the Samaritan was, “If I don’t stop to help this man, what will happen to him?

* * * * * * * *

One of the challenges we confront when reading ancient texts is a fundamental difference in how we tell stories. In a word, we are a “high-context society,” while the Evangelists and authors of virtually every other book in the Bible inhabited a “low-context world.”[8] Allow me to illustrate.

If you were telling this story, you would describe what was going through the minds of each character at every critical juncture in the tale. You would also give a physical description of their appearance, along with the prevailing weather conditions, and the difficulties of traversing the road to Jericho—an 18-mile rocky path which descends 1,700 feet. I could go on; but you get the picture.

The ancients didn’t compose their texts this way because their intended audience was their contemporaries who didn’t require the context we sorely lack. Thus, all of the information we need in order to grasp Christ’s message requires additional work on our part.

Let’s start with the inn and its proprietor to which the Samaritan took the injured man.

The consensus view among biblical scholars is that the Samaritan sought lodging at an Inn in Jericho. These inns were only found in villages, of which there were none between Jerusalem and Jericho.[9]

But the last place anyone would want to spend the night after a long day of traveling in Palestine in the first century was a public inn. These places were filthy and offered little in the way of comfort: just an open square surrounded by a wall, along with an uncovered space for animals. People were typically sheltered by only a wooden, open-air cloister, though a few very small rooms were available for wealthy travelers.[10] And the innkeepers? Crooks, swindlers and thieves, the lot of them.[11]

Mercifully, these inns were few in number because hospitality was considered a great virtue among both the Jews and Samaritans—one essential to the preservation of their respective communities. If you needed a place to stay for the night, you simply knocked on the door of the first home you spied and made your request. If asked, you would give the customary recitation of your lineage; and nine times out of ten you would receive a warm welcome.[12] But this was only true if the owner of the home where you sought lodging was also of your faith. Since Jericho was almost exclusively inhabited by Jews and the local population loathed Samaritans even more than their Jerusalem counterparts, the only option for our Samaritan was a public inn. And even there, the risk to his person was great. This was enemy territory.

* * * * * * * *

Before we proceed, I wish to correct a common misconception: that the Samaritans were oppressed by the Jews. They were not. They were the largest demographic in many communities in first-century Palestine, they travelled often, and they were a people of means.

No, the Jews did not oppress the Samaritans. They detested them. And the feeling was mutual. The hatred was so intense that some of Christ’s listeners would likely have whispered to themselves, “I would rather die than be rescued by a filthy Samaritan.”[13] Indeed, the very idea that any Samaritan could do anything worthwhile was alien to the Savior’s audience. But why?

* * * * * * * *

The Samaritans, as a distinct group of people, originated after the United Monarchy, governed first by David and then by Solomon, split into two independent states crica 930 BC. To the north was Israel/Ephraim (aka the Northern Kingdom), while to the south, Judah (aka, the Southern Kingdom) reigned supreme. The capital of the Northern Kingdom was situated in Samaria.

After the Assyrians conquered the Northern Kingdom in 722 BC, the King of Assyria brought people from communities throughout the Middle East (e.g., Babylon, Avva, Sepharavaim, Hamath, Cuthaha) and, according to 2 Kings 17:24, “placed them in the cities of Samaria in place of the people of Israel.” Unsurprisingly, this did not sit well with the Israelites.

The feud between the two peoples waxed and waned over the years … actually, I should say, “over the centuries.”[14] But it was red hot when Christ delivered his parable, primarily because both sides enjoyed defiling the holy sites of the other. The Jewish High Priest and King, John Hyrcranus (134 BC– 104 BC) destroyed the Samaritan temple on Mt. Gerizim around 111-110 BC.

And the Jews, according to Josephus, were still fuming over the defilement of the temple in Jerusalem, perpetrated by a band of Samaritans in 6 AD, who scattered the bones of dead people in the sanctuary.[15] So, there’s no oppressing going on here; just two peoples with equal resources whose disdain for each other has only been surpassed, in my opinion, by the religious wars in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries.

* * * * * * * *

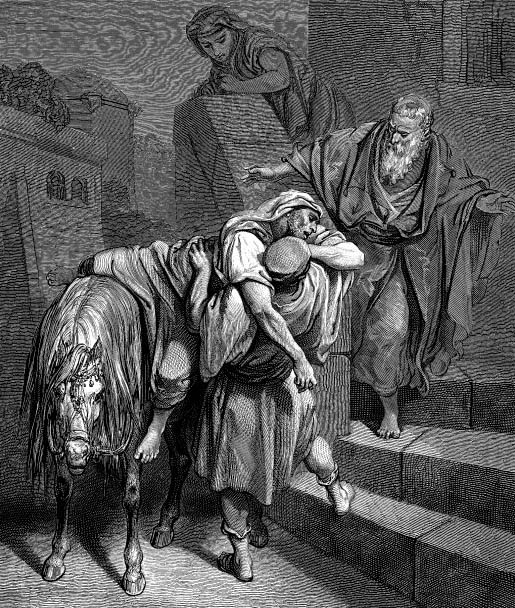

Having secured lodging for himself and the injured man, he spent the night caring for him. But because he had pressing business elsewhere, the next day our Samaritan tendered two denarii to the Innkeeper to cover room and board for the injured man in his abscence. And he promised to make-up any shortfall upon his return. Two denarii, by the way, was a substantial sum, enough to cover the cost of food and lodging for a week or two.[16]

* * * * * * * *

Like so many of Christ’s parables, we don’t know how this story ends. Rather, he leaves the ending to his listeners. What would they do if they were in the position of the innkeeper? He could, while the Samaritan was away, contact the local authorities and falsely accuse the Samaritan of skipping town without paying the injured man’s bill. An unscrupulous innkeeper which, as noted above, there were many, would have been justified in selling into slavery if either the victim of the viscous attack or the Samaritan failed to pay the debt.

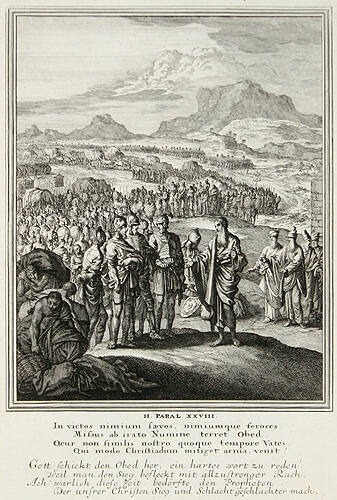

But I believe—as do many biblical scholars[17]—there was an “intertext”—an Old Testament parallel (2 Chronicles 28)—which Christ was hoping his audience would remember; a time when a group of Samaritans captured around 200,000 Judean women, sons, and daughters during a brutal conflict involving Judah, the Samaritans, the Edomites and the Philistines.

When the fighting neared its end, a prophet named Oded confronted and chastised the Samaritans (here identified as “Israelites”) for taking so many captives, reminding them of the grievous sins they had committed. Chastened, a number of the Samaritan leaders, ordered the immediate release of the prisoners.

[They] took the captives, and with the spoil they clothed all who were naked among them; they clothed them, gave them sandals, provided them with food and drink, and anointed them; and carrying all the feeble among them on donkeys, they brought them to their kindred at Jericho, the city of palm trees. Then they returned to Samaria.[18]

* * * * * * * *

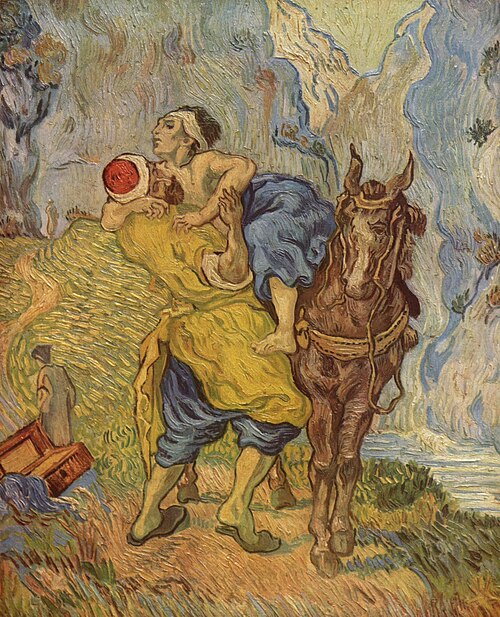

I believe the above painting by Rembrandt of the Samaritan and the Innkeeper, as the former is giving instructions to the Innkeeper before departing on his errand, perfectly captures the hope at the heart of Christ’s story. The matter-of-fact way Jesus recounts this tale—as if everything he had just described was perfectly normal—is the vision of “peace on earth for men of good will” he hopes these two communities will embrace.

As he was preparing to leave, I can’t help but wonder if the Samaritan, by his actions and earnest demeanor, was saying to the innkeeper: “Look, we both know the history of our respective tribes and the enmity between us. But what do we have to show for it?”

“Have I not delivered and cared for an injured man of your faith and paid you a handsome sum to look after him during my brief absence? He is a stranger to me, but each of us is a son of Elohim.

“I know the two of us are bit players in the history of our peoples, but perhaps we can make a difference. I have placed my life in your hands and have promised to return to pay whatever debt I owe. At that time, I hope you will take my hand in fellowship.”

The Samaritan also understood something fundamental the inquisitive lawyer did not: There is no “one thing” you can do to inherit eternal life. In the words of Blaise Pascal, goodness in life is not a certain state; rather, it requires constant movement in a righteous direction.

For this reason, the Samaritan did not simply deliver the injured man to the innkeeper, give him some money, and walk away saying to himself, “Well, I did my bit.” No, he nursed and cared for the man the entire night and then promised to return to further assist with his rehabilitation. This is why we are told that the Samaritan, when he first caught sight of the injured man, “was moved with compassion.” In this context, “moved with compassion” connotes a desire to make the object of the Samaritan’s compassion—the injured man—whole.

Epilogue

Look again at the questions, Christ posed to the lawyer who asked what he needed to do to gain eternal life. In addition, to saying “In the law, what is written?” Jesus also inquired, “How do you read?” We ignore the second question, believing it to be redundant. But that is a mistake. There are no “throw-away lines” in the scriptures.

In Hebrew, the words “neighbor” and “evil” share the same consonants (resh ayin). They differ only in the vowels. But here’s the thing: ancient Hebrew texts do not have vowels—just like many of your text messages. So, both “neighbor” and “evil” are written the same.[19] Hence Christ’s interest in how the lawyer read/interpreted this passage.

As our celebration of Christ’s birth draws to a close and we contemplate our hopes and dreams for the new year, perhaps now would be a good time for each us to look in the mirror and ask the person we see, “How do you read?”

* * * * * * * *

I’m confident Christ would have offered a similar parable to the Samaritans—reversing the rolls of the Jewish innkeeper and that of the Samaritan, of course—had he been given the opportunity. Alas, while enroute to Jerusalem, “he sent messengers ahead of him, who went and entered a village of the Samaritans, to make preparations for him.” But the townsfolk wanted nothing to do with Jesus and his hangers-on. Sadly, this story gets worse.

After two of his disciples, James and John, witnessed this, they asked, “Lord, do you want us to tell fire to come down from heaven and consume them? But he [Christ] turned, and rebuked them, and said, ‘Ye know not what manner of spirit ye are of’.”[20] A spirit of violence and retribution are not welcome in his Kingdom.

But why did Jesus have to “turn” in order to rebuke James and John? Because he was their teacher. As they journeyed to Jerusalem, they, and the other disciples, followed him at a respectful distance. Such is the deference accorded to, and demanded by, all great rabbis. But his having to stop and turn to chastise these two men brought him to a halt, and robbed him of time better spent spreading his message of Peace on Earth, Goodwill Among Men. A reminder that our Savior—not by choice—is compelled to move at our pace, not his. Though, I don’t recommend slowing him down.

[1] See, e.g., Gerrit W. Gong, “Room in the Inn,” General Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, April 2021; Gerrit W. Gong, “No One Sits Alone,” General Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, October 2025. Gong’s approach—an allegorical reading of the parable which he borrowed from John Welch, a law professor at BYU’s Law School—is decontextualization at its very worst and would have been totally foreign to first-century audience in Palestine. It entails treating each character and element of a story as a stand-in for something else. For example, various allegorical interpretations of this parable treat the wounded man as Humanity, Adam and Christ. The wine used to treat his wounds is an exhortation to act, or fear, or the grace of sacraments. The two denarii can be the two testaments, dual love commandments, or knowledge of the Father and the Son. There are no rules. Blake Hudson, “Allegorical Interpretation of the Parable of the Good Samaritan,” Studies In The Bible, https://studiesinthebible.com/articles/allegorical-interpretation-of-the-parable-of-the-good-samaritan/, last accessed on January 4, 2026; see also, 9Marks, “Allegorical Interpretation: Finding the Line Before You Cross It,” March 31, 2020, https://www.9marks.org/article/allegorical-interpretation-finding-the-line-before-you-cross-it/, last accessed on January 4, 2026. Moreover, the very word “allegorical” means hidden. Christ was not a mountebank running a game of three-card monte. The “eyes to see and ears to hear” required to understand his teachings were nothing more than open mind and a receptive heart, with a pinch of faith. Moreover, even assuming Christ did teach in allegories—though I categorically reject the notion that he ever did—it is abundantly clear that the Parable of the Good Samaritan is not an allegory. It was given in response to questions posed to the Savior by an attorney and spoke directly to a major spiritual rift between the Jews and the Samaritans. No questions; no parable. Finally, every allegorical interpretation of scripture is reductionist. In other words, it is a “proof text,” i.e., the decontextualization of scripture to validate the author’s religious beliefs. In this case, Gong and Welch employ the Parable of the Good Samaritan to validate their claim that the Mormon Church is the only true church on the face of the earth and that its Plan of Salvation is the one and only path to heaven—propositions I categorically reject even though I’m a member of that faith: It’s Not All About Us.

[2] Peter Longerich, Heinrich Himmler, (New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012) pp. 309-310.

[3] Amy-Jill Levine, Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of Controversial Rabbi, (New York, New York: HarperOne, p. 75.

[4] Luke 10:25 (NRSV).

[5] Luke 10:26 (NRSV).

[6] Since the thieves had stolen the injured man’s clothing, some have suggested it is not possible to ascertain his identity (i.e., whether he was a Jew, a Samaritan, a Roman soldier, etc.). But since there were no other villages on the road to Jericho—a community the population of which was almost entirely Jewish—it is safe to assume the victim of the assault was a Jew. New Revised Standard Version Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible, (Grand Rapids Michigan: Zondervan Press, 2019) p. 1784. See Also, Kenneth E. Bailey, Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes: Cultural Studies in the Gospels, (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVPAcademic, 2008), pp. 290-291.

[7] Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament, G. K. Beale & D. E. Carson, eds., (Grand Rapids, Michigan: BakerAcademic, 2007), pp. 321-322).

[8] E. Randolph Richards & Richard James, Misreading Scripture with Individualist Eyes: Patronage, Honor, and Shame in the Biblical World, (Downers Grover, Illinois: InterVaristy Press, 2020), p. xxi-xxiii.

[9] Kenneth E. Bailey, Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes: Cultural Studies in the Gospels, (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVPAcademic, 2008)

[10] Henri Daniel-Rops, Daily Life in Palestine at the Time of Christ, (London, England: Phoenix Press: 2002), pp. 262-263.

[11] Bailey, p. 296; Sarah Ruden, The Gospels: A New Translation, (New York, New York: Modern Library, 2021), p. 206, n. ++ (“Innkeepers were notorious for swindles,….”); New Revised Standard Version Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible, (Grand Rapids Michigan: Zondervan Press, 2019) p. 1784 (“innkeepers generally had a reputation as being untrustworthy …”).

[12] Henri Daniel-Rops, Daily Life, supra, p. 262.

[13] Levine, p.96.

[14] Levine, p. 97.

[15] Josephus, Antiquities 13:74. See also, New Revised Standard Version, supra, pp. 1828-1829.

[16] Bailey, p. 295.

[17] Beal & Carson, Commentary, p. 321; Levine, Short Stories, pp.

[18] 2 Chronicles 28:15.

[19] Levine, Short Stories, pp. 86-87.

[20] Luke 9:55 (KJV).

Certainly the story is as you say about Christ urging the listeners not to stick to divisions among people. But can I add something? the question that Christ is responding to (in my not-so-enormous experience) is usually translated as “who is your neighbor?” So I’ve always felt the story is showing us that our neighbor is right under foot. We will trip over him or her on our paths. We actually have to step over them or walk around them to avoid recognizing our neighbor. This is probably the only parable that always struck me as pretty clear (due to my limitations, not the parable). Who’s your neighbor? You will see them in front of you unless you are trying to avoid them.

Cathy, that is an excellent observation. I probably should have, at least briefly, touched on that point, but I chose not to for a couple of reasons.

First, the question of “who is our neighbor?” is what everyone in Sunday School, since they were tykes, has always associated with this parable and could probably recite from memory.

Second, my principal focus was on the application of that principle in the historical context of the visceral relationship between the Jews and the Samaritans. Most Christians, I’ll wager, are oblivious to the risks the Samaritan took in this story. In all probability, he would be killed in Jericho before he ever returned to that inn. Further, the New Testament conveys the distinct impression that the Samaritans were an oppressed and marginalized minority in Palestine. Nothing could be further from the truth. This is what, I believe, gives this parable such immediacy, begging the question, “How can we as Jews and Samaritans reconcile and end this bitter feud?” This was a societal problem for them. And I, not-so-subtly, was underscoring a similar problem in our country.

But, as I said, I’m glad you made your observation regarding the importance of understanding who comes under the umbrella of the term “neighbor.” (Everyone, of course, according to Christ.)

This is very educational, thank you.

One point, probably obvious — I’m guessing that the Samaritan told the innkeeper he would pay more money later was to give the innkeeper an incentive for good behavior. That way it was more profitable for the innkeeper to take good care of the injured man than to exploit or further abuse him.

I believe you are correct, Doug, though I’m not sure your point is an obvious one. (That’s my roundabout way of saying “thank you” (again) for adding context I should have included in the essay.)

This was an educational experience for me, too. Though if I were to attempt a deeper dive into the origins and history of the rift between Jews and Samaritans, I would likely suffer brain damage, given the number of moving parts, name changes, different opinions regarding “who hit Jane first,” etc.

Well done. As always, you provide depth and context and increase my understanding of the Bible. For that, thank you. Only recently have I started to appreciate the rivalry between the Jews and Samaritans. I may have been a terrible Sunday school student, but while I heard the terms, I was unclear about the meaning. However, you provide further context. The rivalry was fiercer than I thought. Additionally, I was unaware of how treacherous it would have been for the Samaritan or the risk taken. A fairly obvious conclusion that I would have missed until now is that your neighbor includes people you do not like and you may be called to risk your life for one of them.

But I also want to comment on your conclusion. I had not appreciated that aspect until now. The Samaritan treated the innkeeper with respect and trust, even if the innkeeper may not have earned either of them. It reminds me of a line from the movie Frozen, the Samaritan did “the next right thing.” This lesson is as evergreen now, as the political and cultural divide seems to grow daily in America, as it was back then. Thank you for the though provoking essay.