One day in the mid-1960s, I wandered into a music store in downtown Champaign, Illinois. By “music store” I mean a store where you can purchase musical instruments, sheet music, and the like.

While perusing the rock-and-roll section, I spied a piano arrangement of the Beatles’ hit song, “Yesterday.” This is what I had been hoping to find: a soulful tune that, if played with deep emotion, would prompt the cool girls in my junior high school to notice me. The moment I returned home, I headed straight for the Yamaha upright in our living room and began to practice the song.

I had quit taking lessons a couple of years before because my teacher—an elderly woman who I’m convinced was of Prussian heritage—had rapped my knuckles with a ruler when I began my weekly lesson by playing “Greensleeves” (aka, “What Child is This”).

She objected not to the quality of my performance, but to my failure to practice the Czerny exercises I had been assigned the previous week. (For the uninitiated, Carl Czerny was a nineteenth-century Austrian musician who composed several piano exercises and etudes for young beginners. With rare exception, male adolescent piano students hate it.)

My father took notice of my renewed interest in tickling the ivories. He could see my talent—he had briefly studied classical piano in his youth before his father died unexpectedly and money became tight—but knew it would not develop properly without the help of a professional. So, he made me a proposition: “If I find you a piano teacher who will teach you the music you want to play, will you agree to take lessons again and practice this time?” “You betcha!” I replied.

My new teacher, whose name I do not remember, was an accomplished pianist and a doctoral student in the School of Music at the University of Illinois. More importantly, he was cool—and had the facial hair to prove it. The store where he worked had all of the Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, Burt Bacharach, and Moody Blues sheet music I craved, and was happy to relieve me of my weekly earnings from mowing lawns.

As part of my instruction, my teacher taught me to analyze music, to dissect the organizational framework and harmonic progression of a piece. This exercise soon revealed that there were few discernible differences in the songs I was playing.

Most of them had a simple AABA structure, each letter referring to a musical phrase and the frequency with which it is repeated in the song. And typically, only four chords were used—three major, one minor[1]—to carry the tune. Many song writers apparently were so exhausted after rehashing this formula, they didn’t have the energy to write a coda to finish the piece. Instead, the performer was told to repeat the last four measures a few times and simply fade away….

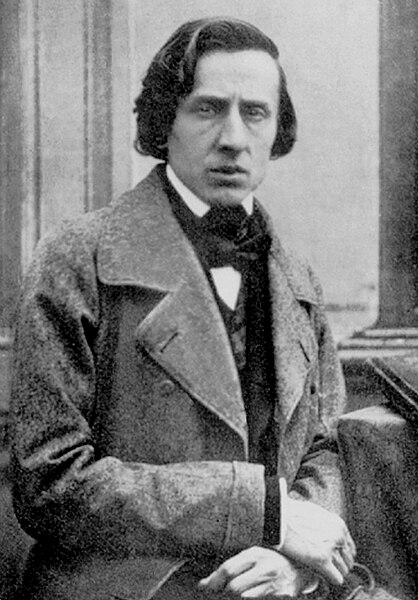

One day my teacher began our lesson by saying, “Move over. Now, listen to this.” He proceeded to play Chopin’s Nocturne in E-flat major. I was mesmerized. The pop songs I had been playing were musical twinkies compared to what I had just heard.

After the Chopin Nocturne, he taught me Rachmaninoff’s 18th Variation on a Theme by Paganini, a Brahms’ Intermezzo, a Romance by Sibelius, a couple of Bach Inventions, along with several other classical works. Next came jazz compositions by Oscar Peterson, Vince Guaraldi, and Duke Ellington. The intricacy and beauty of this music cast a spell over me which has never been broken.

By this time high school was drawing to a close and college loomed on the horizon. I secured admission to the School of Music at Brigham Young University, hoping to earn a degree in musical composition. But then reality slapped me in the face.

Though I excelled in the course work my freshman year, my musical talent—especially my technique and aural skills—were not in the same league as those of my peers. Reluctantly, I set aside my dreams of a career as a performer and composer and changed my major to pre-law. (Damn it! That old Prussian woman was right. I should have practiced my Czerny!)

Thanks to the gentle wisdom of my father and second piano teacher, music has greatly enriched my life. For starters, I married a fellow musician, someone who had the talent to earn a bachelor’s degree in Piano Pedagogy (yes, she had practiced her Czerny). As a bonus, her dowry included the family’s Steinway baby grand. Though I was so smitten with her I would have settled for a “Schroeder-esque” piano. (Who needs those black keys anyway!)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Over the years I have derived great pleasure from performing in church and at the weddings of friends and family members. I have also been asked to provide the music at memorial services—one time for a complete stranger.

One Friday morning six years ago, a friend and former law partner asked me if I could, the following day, provide the music at a memorial service for the uncle of one of his colleagues. The pianist lined up by the family had bailed on them at the last minute. When I told him I would be glad to help out, he said, “Great. Oh, and by the way, you can’t play any religious music; just classical and other stuff.’”

The memorial service, I learned, was being held at the Washington Ethical Society. I rolled my eyes and thought to myself, “What could I, a practicing Mormon, possibly have in common with a bunch of atheists?” Quite a bit, as it turns out.

John (the deceased), I discovered, had worked for the Peace Corps in Chile during the late 1960s where he met his wife. I served a mission for my church in Chile in the early 1970s where I also met my wife, Margaret. His niece told me John was a big fan of Alan Taylor, a well-regarded historian who has authored several fine books on early North American history, many of which I had read. Coincidentally, about fifteen years ago, I met Professor Taylor who was working as a consultant for an Indian Nation I represented in connection with a case it had before the United States Supreme Court. Finally, John also shared my passion for classical music.

While I was playing the piano, Pat, John’s widow and life partner of fifty years, planted herself beside me on the piano bench. She told me how much she loved my musical selections, some of which were personal favorites of her late husband. I responded by saying that it was a privilege to be there and to be a part of such a spiritually uplifting gathering. Wrapping an arm around my shoulders, she gave me a hug, and said, “Well, I guess that means we’re both happy.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

What I have enjoyed most of all is playing for senior citizens in nursing homes. The residents always lift my spirits and never fail to show their appreciation—though some of the women have, on occasion, expressed their gratitude with unexpected enthusiasm. (Some pinch marks on my derriere and bruises on my neck elicited a raised eyebrow and a few questions from Margaret.)

A few years ago, the entertainment coordinator for a local nursing home asked if I would entertain the patients in their Alzheimer’s ward on Christmas Eve. Since seasonal carols are my favorite part of the holidays, I was happy to oblige.

When I arrived at the appointed hour, I was directed to a room in the basement where about 25 patients were seated along two walls in a small room. Only one or two acknowledged my presence; the rest were catatonic and didn’t seem to react when I began to play.

But after a while, a few patients began to show signs of faint recognition, as if the melody of “Jingle Bells” or “Silent Night” had briefly penetrated the plaques and tangles encrusting their brain cells. Some began to mouth some of the words to the song and sway, ever so slightly, to the rhythm.

This experience reminded of a short fairy tale written by Hans Christian Andersen called, “The Writing on the Wall.” It is narrated by the Moon who prefaces and concludes his story with these words, “Through the silent vaults of air I look down on the drifting clouds and see great shadows over the earth below.”

One evening, the Moon cast his gaze upon a prison and a carriage waiting to transport one of its residents. His rays “pierced the iron bars of the window” of the prisoner to be brought forth “and saw him writing something on the wall.” To the Moon’s surprise, words had not been inscribed “but a melody, a last outpouring of his soul, a farewell to the place he was about to leave that night.” The Moon instantly grasped why the prisoner had chosen this medium of expression: “for where words fail, music speaks.”[2]

Ten years ago, the transcendent power of music—its ability to convey ideas and emotions which cannot be put into words—touched my life in yet another way.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

In March 2013, I went to Israel to tour the Holy Land. I arrived one week before Passover, so Jerusalem was awash with pilgrims and tourists.

When I travel, I often carry a three-ring binder of sheet music in hopes that the hotel where I stay will have a lounge with a piano. As luck would have it, the Ramada Israel had a baby grand, which the manager graciously allowed me to play one evening.

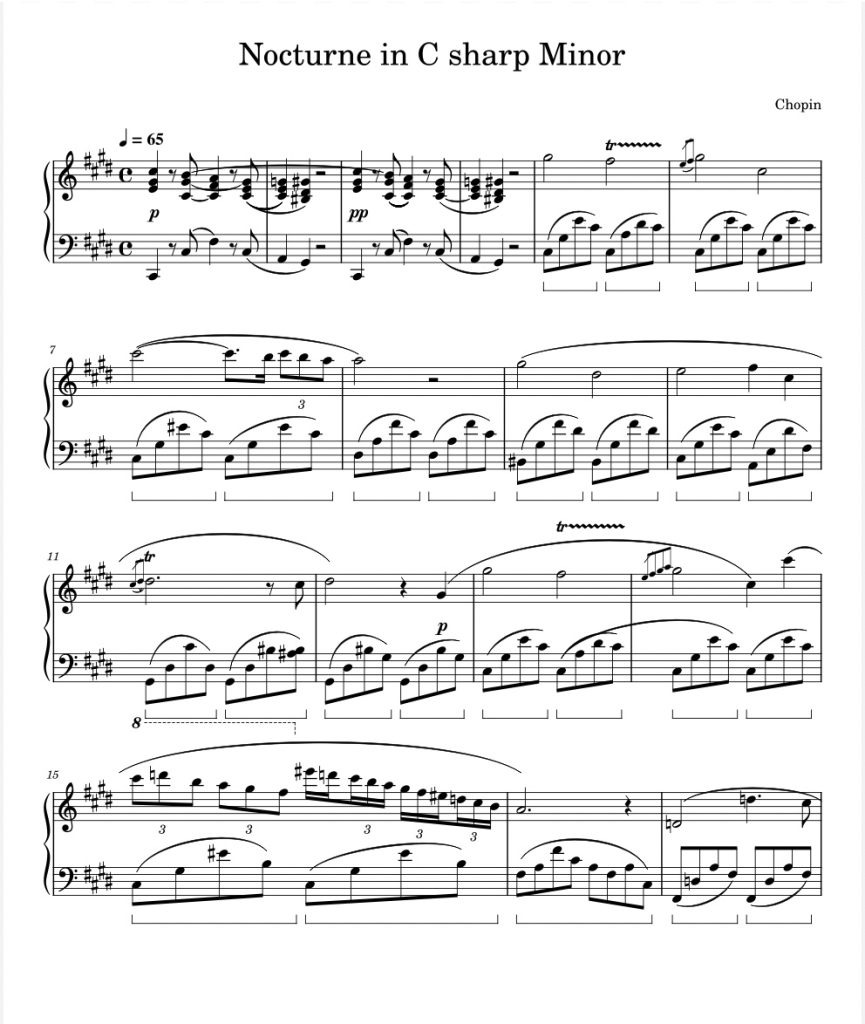

After I had been playing for a while, a twenty-something Orthodox Jew with an Eastern European accent approached me and said, “I realize this is a longshot, but do you happen to know Chopin’s Nocturne in C-sharp minor?” I not only knew it and had a copy of the score in my binder; I was well acquainted with its historical significance to both the Poles and Jews.

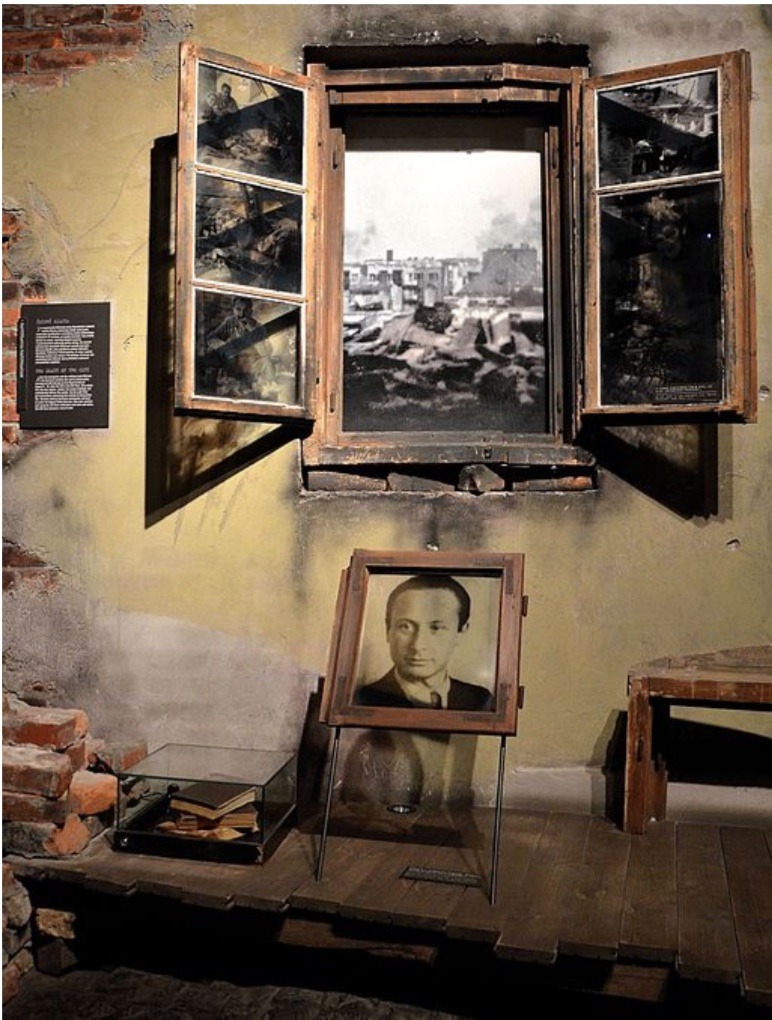

On September 23, 1939, three weeks after Nazi Germany set in motion the Second World War by invading Poland, the Polish-Jewish pianist, Wladyslaw Szpilman, was playing Chopin’s Nocturne in C-sharp minor (op. posth.) live on Polish Free Radio. But he could barely hear what he was playing because of the incessant noise created by German shelling. His was the last live music broadcast from Warsaw. Shortly after the conclusion of his performance, the station was silenced for the duration of the war when it was struck by a bomb.[3]

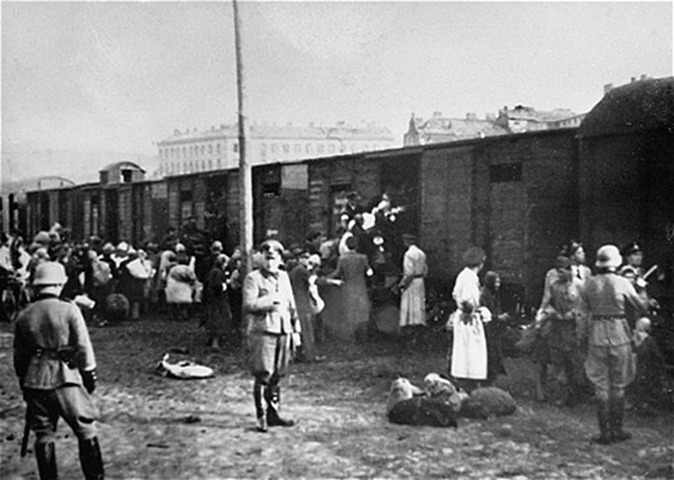

One year later, Szpilman and his family were evicted from their home and herded, along with 450,000 other Jews, into the Warsaw Ghetto. As if to compound the humiliation and depravity of their plight, the proclamation establishing the creation of the Ghetto was issued on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in Judaism.[4]

Disease and starvation were rampant, killing more than 5,000 people a month by August[5]—not counting the 300,000 Jews who were transferred to the Treblinka and Majdanek concentration camps for extermination.[6] Those who remained in the Ghetto were subjected by the Nazis to slave labor.

In 1942, Szpilman’s parents, along with his brother and sisters, were rounded up for deportation to Treblinka where they were executed. While they waited to board the train to the concentration camp, Szpilman—but only him— was yanked out line and told, “Go on, save yourself!” Having been spared by a member of the Jewish Police[7] who recognized him as a prominent musician, it suddenly dawned on him what awaited the rest of his family and the other people boarding the cattle trucks.

Szpilman was forced into hiding, frequently changing his place of refuge to avoid capture.[8] One day, while searching for food his luck ran out. He was caught by a German officer. While interrogating Szpilman, the officer asked: “What do you do for a living?” “I’m a pianist,” he replied. But the officer was suspicious and ordered him into a room where a piano stood against the wall, and said, “Play something!”[9]

It had been two and a half years since Szpilman had touched a piano. His hands were filthy and his nails had not been cut for weeks. Szpilman’s fingers trembled as he raised them to play as commanded, knowing that his life hinged upon this one performance. He elected to play Chopin’s Nocturne in C-sharp minor.[10]

When he finished, the officer looked at him without saying a word. He then ordered Szpilman to show him the attic where he had been hiding. The officer then found him a more secure location in a loft and offered to bring some food. Szpilman couldn’t restrain himself any longer and asked, “Are you German?” The officer’s demeanor suddenly changed from solicitous to anger, and he barked his response: “Yes, I am! And am ashamed of it after everything that’s been happening.”[11]

The hypnotic appeal of Chopin’s music lies in its liberal use of tempo rubato, which means “stolen or robbed time.”Rubato grants the musician permission to adjust the time allotted to the notes of each measure and phrase, stretch the limits of convention, and make the music her own. In the words of the virtuoso pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Chopin’s music speaks to the Polish people because it “rejects the fetters of rhythmic rule, and refuses submission to the metronome as if it were the yoke of some hated government: this music bids us hear, know, and realize that our nation, our land, the whole of Poland, lives, feels and moves in Tempo Rubato.”[12]

Chopin, in a very real sense, is considered Poland’s founding father, its “supreme leader.” In 2018, when Poland celebrated the centennial of its independence as a nation, President Andrzej Duda declared that without Chopin, Poland would have remained under control of its authoritarian neighbors. “It was thanks to his music,” Duda said, “that Poland re-emerged on the world map in 1918.” No wonder the Germans banned Chopin’s music after they invaded the country in 1939.[13]

Chopin’s music speaks to the Jews as it does to the Poles. The minor key in the nocturne Szpilman chose to play for the German officer captures the melancholic essence of Jewish history but ends with what is called a “Picardy Third,” a bright major chord, evoking a sense of optimism and hope for the future. Hope and resilience have sustained the Jewish people for centuries. Only a fool would bet against them.

When I had finished playing Chopin’s Nocturne in C-sharp Minor at the Ramada Israel for the young Orthodox Jew who had requested it, I turned to look at him and his family. There were tears in their eyes as there were in mine.

Over three thousand years ago the Jews fled Egypt after enduring centuries of brutalization at the hands of the pharaohs. That event is celebrated each year during Passover, which was about to begin as we departed Israel on March 20, 2013. Today, antisemitism has once again reared its ugly head throughout the world. New pharaohs have emerged—in Western Europe, the United Nations, the halls of the Congress, America’s universities, our country’s once-trusted newspapers, and the streets of our cities where members of our President’s own political party have Christened him “Genocide Joe” because of his support for Israel.

I firmly believe the promised Messiah will, at the appointed hour, come for the Jews. But as for the rest of us, I have my doubts.

[1] These invariably were the tonic, the sub-dominate and the dominant, and a minor sixth. In the key of “C” that would C, F, G & A-minor.

[2] Hans Christian Andersen, The Hans Andersen Story Books for the Young, (Ward Lock & Tyler: London, 1887), pp. 93-94.

[3] Władysław Szpilman, The Pianist: The Extraordinary Story of One Man’s Survival in Warsaw 1939-45, (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2002), pp. 38-39.

[4] “An Exercise in Depravity: The Establishment of the Warsaw Ghetto,” The National World War II Museum, New Orleans, Louisiana, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/exercise-depravity-establishment-warsaw-ghetto#:~:text=To%20magnify%20the%20humiliation%2C%20the,the%20Jewish%20Day%20of%20Atonement, last viewed on December 29, 2023.

[5] Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, (April 17, 2023), https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/warsaw, last viewed on December 28, 2023.

[6] Norman Davies, Rising’44: The Battle for Warsaw, (Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, (New York, New York: Viking Penguin, 2004), pp. 100-101; Lucy S. Dawidowicz, The War Against the Jews, The War Against the Jews, 1933-1945, (New York, New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1975), pp. 308-309; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, (April 17, 2023), https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/warsaw-ghetto-uprising, last viewed on

[7] The Jewish Police and Jewish elders collaborated with, and agreed to assist, the Germans in keeping order in the Ghetto and, in some instances, the killing of Jews. In return, they enjoyed certain privileges (e.g., better housing, food) and the (false) hope of being spared the fate of deportation to Treblinka. Before condemning these individuals, we would do well to heed the counsel of Norman Davies, the author of Rising ’44: “[Those] living in freedom in another age should not rush to pass judgment. Every person, every community has its breaking point. People will bear deprivation and humiliation with a mixture of fatalism, resignation, and fortitude. But they can’t do so indefinitely.” Rising ’44, p. 101. Primo Levi, author of Survival in Auschwitz, restrains our impulse to judge even further by noting that the true heroes are not the Holocaust survivors but those who sacrificed for their fellow prisoners (e.g., sharing their food rations) at the expense of their own lives.

[8] Ibid, pp. 104-114.

[9] Ibid, pp. 176-177.

[10] Ibid, p. 178.

[11] Ibid, pp. 178-179.

[12] Annik LaFarge, Chasing Chopin: A Musical Journey Across Three Centuries, Four Countries and a Half-Dozen Revolutions, (New York, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020), p. 21.

[13] Ibid, pp. 22-23.

I enjoyed this blog. Happy New Year! – James

What a thoughtful post. Thank you for posting, Eric. I am also concerned about the rise in anti-semitism. History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.

Hopefully all good things in 2024. Happy New Year!

Thank you Eric!!!