Since Advent begins today, it seems appropriate to turn our attention to the infancy narratives found in the first two chapters of Matthew and Luke.

When we study these scriptures, we typically skip over the verses at the beginning, which deal with the Savior’s ancestry. I imagine we do this because we assume they do nothing more than recite Christ’s lineage, just like the family trees we create on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org. We also may be a bit perplexed by the numerous differences between Matthew and Luke’s genealogies.

But our assumption regarding the nature and purpose of these pedigrees is wrong, which explains both our confusion regarding the apparent inconsistencies between the two lineages and our inability to grasp what the evangelists are trying to teach us. To understand these important teachings, we first need to set aside our concept of ancestry and learn what it meant to those who lived in the first century.

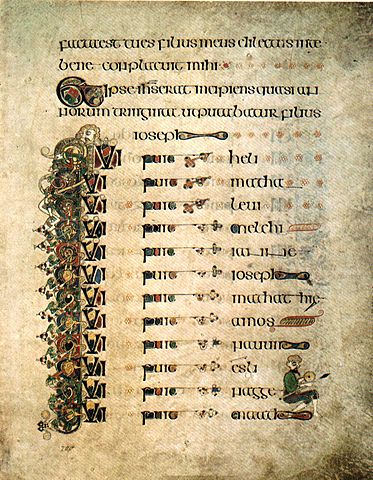

Ancient Semitic genealogies only rarely were written to document strict biological lines of descent.[1] Thus, when somebody “begat” a child, that offspring was not necessarily a product of biology. This is implicit in the Hebraic and Aramaic meaning of the word “son,” which can indicate a covenant usage, class membership, or certain characteristics (e.g., royalty) possessed by the named individual.[2]

Most ancestral records at the time of Christ were crafted “to show identity and duty, to demonstrate credentials for power and property, to structure history, and indicate one’s character.”[3] Matthew’s account—which is the focus of this essay—employs all of these devices and more to tell the story of Christ’s origins and foreshadow his earthly ministry.

Often overlooked is how Christ’s genealogy differs from those found in the book of Genesis where an individual’s lineage was followed by a list of persons who depend on their ancestor for their meaning. By contrast, Matthew lists not Jesus’ descendants, but his ancestors who depend upon him for their meaning. He carefully chooses Christ’s forefathers to elucidate his mission and the “good news” he will bring to mankind. Thus, Jesus’s story does not begin with his birth, but with Abraham begetting Isaac.[4]

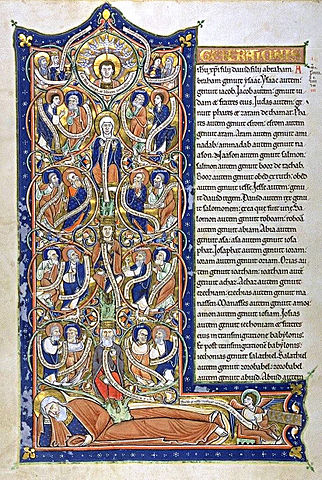

Matthew tells us how he has arranged Christ’s lineage in chapter 1, verse 17: there are 42 generations in all, which are presented in a repeating structure of three sets of fourteen. This arrangement allows Matthew to underscore the overarching importance of the Savior’s Davidic heritage, since the number fourteen is the numerical equivalent of David’s name in Hebrew.[5] (The Israelites were really into numerology.)

These groupings encompassed the three epochs of Israel’s history: (1) The Patriarchs, (2) The Kings, and (3) what the biblical scholar Raymond Brown labels “The Unknown and The Unexpected,” an obscure cast of characters from the period of Babylonian captivity to the return to Jerusalem. And the first verse of Matthew’s gospel—“An account of the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham”—gives us three names, in reverse chronological order, as reference points for these three categories.

With this understanding, we can now answer the question: What was Matthew trying to teach us with his artfully constructed ancestry of Jesus the Messiah?

Let’s start with the first three named descendants of Abraham—Isaac, Jacob and Judah—who all have one thing in common: none of them was the firstborn of his father. For a culture that places great emphasis on primogeniture, this would have been startling. In addition, Jacob’s birthright was something he acquired from his older brother, Esau, by something less than honorable means. And what’s up with Judah? Wasn’t Joseph the one favored by God and a better expression of Christ than Judah, who sold his brother and sought out prostitutes?

The point the author is trying to make is that God frequently does not choose the best and the brightest. He is unpredictable, giving little thought to tradition or merit, in order to remind us that our salvation ultimately depends upon his grace and that of his son, who was sent to preach to all, especially tax collectors and sinners, the ones in greatest need of a physician. This also subtly implies that the Abrahamic Covenant, a pact originally between Jehovah and the Jews, would eventually be extended to all of God’s children.[6]

The first section of Matthew’s genealogy builds up from an Abraham, who had no land, to a David, who ruled as king in possession of the Promised Land. While David was, indeed, the greatest and most successful king of ancient Israel—the only one of the bunch referred in the Old Testament as “the King”—he was hardly a saint. And after his reign, everything pretty much went south, ultimately ending with the loss of the land and deportation to Babylon. Of the fourteen Judean kings, only two, Hezekiah and Josiah, can be described as righteous; the rest were a collection of idolaters, incompetents, and ne’er-do-wells.

Notwithstanding his grievous mistakes, David did acknowledge his errors and sought the Lord’s forgiveness. As a result, Jehovah promised him that he would “establish the throne of his [David’s] kingdom forever.”[7] Further, as noted by LDS scholar Eric D. Huntsman, Matthew’s reference to the collapse of the monarchy and the exile in Babylon prepares us to see that the Lord’s covenant with David would ultimately be realized in some other way,[8] which brings us to the final section of Matthew’s genealogy.

This is, indeed, a most curious cast of characters. Apart from the first two (Shealtiel and Zerubbadel) and the last two (Joseph and Mary), none of them made it into the story of Israel for having done something significant. But that is Matthew’s point: while powerful monarchs brought God’s chosen people to ruin, unknown individuals, who undoubtedly consisted of both saints and sinners, were the vehicle of their restoration. The Lord, once again, accomplished his purposes through people who, because of their obscurity, were considered insignificant and forgettable by earthly standards.

In addition, Matthew presages the important role of women in Christ’s ministry by including four of them in the Savior’s ancestry: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and Bathsheba (the wife of Uriah). What’s more, two of these women were Canaanites and third, Ruth, was a Moabite.

My favorite of the bunch is Ruth who, upon the death of her husband, threw herself at the feet of one of his relatives, Boaz, an Israelite, and implored him to marry her, which he did, notwithstanding the derision he certainly endured for marrying outside the faith. Her child was to be the grandfather of David the king. This resonates with me because my father also married a person not of our religion. These women, all of whom had a marital history that contained elements of scandal or scorn, serve to introduce Mary, whose marital situation is also peculiar since, according to Matthew, she became pregnant not via conventional means but “through the Holy Spirit.”

The last, and perhaps most important, lesson of Matthew’s lineage of the Savior is that it is not solely retrospective; rather, it has a sequel that involved as many saints and sinners as did his ancestors. It starts with Peter, who denied the Christ, and Paul, who persecuted him. And it continues down to the present day. As Raymond Brown observed: “The God who wrote the beginnings with crooked lines also writes the sequence with crooked lines, and some of those lines are our own lives and witness.”[9]

We, a peculiar and diverse mélange of individuals, are the Savior’s descendants, people who have delighted and disappointed him in equal measure. The Advent liturgy found in Matthew teaches us to ignore the circumstances of our birth—they neither enhance nor diminish our stature in the eyes of God. It also instructs us to honor everyone, including the weak and lowly, who helped set the stage for Christ’s ministry and who continued his work after his ascension, even unto the present day. When we heed these teachings, we add to the legacy of Jesus the Messiah and lay claim to our rightful place as his heirs.

[1] Joel B. Green, Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels, (IVP Academic: Downers Grove, Illinois, 1992), p. 255.

[2] William Smith, Smith’s Bible Dictionary, revised and edited by Rev. Fn. and M. A Peloubet (Zondervan Publishing: Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1984), p. 210.

[3] Green, at 255. See also Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler, Editors. The Jewish Annotated New Testament, 2nd Ed., (Oxford University Press: New York, 2017), p. 11 (Genealogies in early Jewish Greek and Roman literature “served to praise heroes and heroines by glorifying their past as well as adding legitimacy to their narrative.”).

[4] Raymond E. Brown, A Coming Christ in Advent, (The Liturgical Press, Collegeville, Minnesota, 1988), p. 18.

[5] John Barton and John Muddiman, Editors, The Oxford Bible Commentary, (Oxford University Press: New York, 2001), p. 848.

[6] Brown, p. 20.

[7] 2 Samuel 7:13 (NRSV).

[8] “Teaching Matthew’s Genealogy (Matt. 1),” Eric D. Huntsman, Brigham Young University New Testament Commentary (January 9, 2015).

[9] Brown, p. 25.

Fascinating. Matthew – and Eric – seizing every opportunity to teach us. Thank you for sharing this beautiful, good news!

Great to hear from you, Daniel! You are sorely missed on the East Coast.

And thanks for your kind and encouraging words. Much appreciated.

That was an intriguing analysis of a part of the scriptures very rarely discussed, thank you.

Thanks, Jeff. We often miss much of what the scriptures have to teach us because we read them through modern eyes, not through the eyes of the people who wrote. We blithely assume that genealogy was practiced the same in ancient times as in ours, which is false. This is due, in part, to the erroneous notion that the doctrines taught and practiced in the past are no different than those we embrace today. While the fundamental principles of the gospel are unchanging, the way they are understood, communicated and implemented through time varies greatly. Indeed, in our own day, the Mormon Church of the 19th century differs significantly from the one we see today.

Fascinating look at a part of the scriptures that I regularly skip over. I appreciate the insight this gives us into to who we are and what we can glean by looking at our heritage. In the end we are rewarded and punished for our own actions not those of others and the 2nd article of faith so powerfully puts it, ” We believe that men will be punished for their own sins, and not for Adam’s transgression, and not for Adam’s transgression.” This also means we will be rewarded for our own goodness not for the things accomplished by others in our family.