Around 1:00 am on Monday, June 20, 1987, I awoke with severe chest and abdominal pains. When they failed to subside, I asked Margaret to call an ambulance. By the time we arrived at the hospital in suburban Maryland, I was nauseous, running a high fever, and experiencing chills.

Later that morning my personal physician arrived. After reviewing the results of my blood work and other tests and conducting a physical examination, he ruled out a bleeding ulcer or any problem with my other body organs. But he still could not identify the source of the problem. All the while, the pain began to worsen, and I was given nothing to alleviate it for fear that the medication would mask my symptoms, thereby making it more difficult to diagnosis my condition.

I spent an uncomfortable night in the hospital by myself because Margaret had to retrieve our three young children who were in the care of a neighbor. By Tuesday morning the pain had abated considerably, though I was exhausted and weak. Because no one was able to ascertain the cause of my symptoms and since they had largely disappeared, I was discharged. But several hours later the agony returned with a vengeance. So, for a second time in less than 48 hours, I was being rushed by ambulance to the emergency room.

Once again I was admitted to the hospital but given no medication to relieve the pain; further, no progress was made in diagnosing my illness. The following morning a resident specialist in internal medicine performed an endoscopy, which revealed nothing. There were, however, some anomalies in my latest blood tests, so he decided to order an ultrasound.

When Margaret returned to the hospital Wednesday afternoon, she inquired as to whether my ultrasound had been performed. She was told that it would have to wait until the next day since all of the technicians had gone home. Margaret was not amused. She could see that my condition was deteriorating; nevertheless, the hospital and my attending physicians refused her request to have the test performed on an emergency basis.

That evening, my personal physician called Margaret and told her he thought I might have some kind of viral or bacterial infection or neurological disorder. So he ordered several imaging tests and a spinal tap, all of which would be performed that night.

For the uninitiated—and I pray you forever remain so—a spinal tap requires the patient to lie on his side with his legs flexed at the knees and pulled in towards his chest. This stretches the lower back, facilitating the lumbar puncture and withdrawal of spinal fluid. This is not a pleasant experience under any circumstances, but for someone with acute abdominal pain, remaining motionless in the fetal position is sheer torture. And my misery was compounded by the supervising doctor’s decision to have an intern perform the procedure, who struggled to insert the needle correctly. The test results were negative.

Shortly thereafter, a technician came to my room saying he needed to take some more blood because the lab had apparently misplaced the last sample. At that point I completely lost it. I can’t remember exactly what I said but I believe the words “blood suckers,” “Dracula,” along with a string of carefully chosen expletives, crossed my lips.

After he left (without my blood) and I had calmed down, I resigned myself to my fate and offered one final prayer: “Listen God, if this is the end, I won’t hold it against you. But could we please just get this over with.” I then slipped into a fitful sleep.

Early Thursday afternoon, I finally received the ultrasound examination, which revealed a problem with my gall bladder. It was full of stones some of which had escaped into the bile duct. Surgery was scheduled for that evening and, because of the severity of my condition, a specialist at a neighboring hospital, who was also the back-up surgeon for the President of the United States, was recruited to perform the operation.

When I awoke the next morning, there was an IV in each of my arms, two drainage tubes in my abdomen and, just above them, a seven-inch horizontal incision sealed with stitches and staples. (No more two-piece bathing suits for moi.)

Shortly thereafter, the surgeon stopped by. The first words out of his mouth were, “You were a mess. Another 24 hours, and you would have been dead.” He said that the swelling of my gall bladder, along with the peripatetic gallstones, had perforated my GI tract, releasing toxic waste into my abdominal cavity. This resulted in a bacterial infection called peritonitis, which can lead to sepsis. Ordinarily, gallbladder disease is detected long before it advances this far because most people experience pain from the gallstones or other symptoms. I was one of the few who did not.

There were other things going on in our lives at this time. First, in one month we were scheduled to close on the sale of our current residence and the purchase of a new home in Northern Virginia. Second, several months earlier it became clear to me that the law firm where I worked was experiencing serious financial problems from which it probably would not recover. So I immediately began to search for new employment.

A few days before my medical emergency, I had a successful second interview with a highly regarded D.C. firm. I was counting on an offer from them since it was unclear whether my current employer could stay afloat much longer. But I was worried my suitor would lose interest if they had doubts about my ability to start work soon or my overall health in general. And if the bank financing the purchase of our new house learned we were about to lose our only source of income, they would not approve our loan but we would nevertheless be obligated to proceed with the sale of our current home.

About an hour later, my parents arrived at the hospital. They lived in Illinois and Margaret had kept them apprised of my condition throughout the week. They were planning to fly to Las Vegas on Thursday for a special family gathering but, as my condition continued to decline, they felt they had to come to Washington.

Both my parents were concerned about our children, especially Ryan, who, at age ten, was old enough to understand what was going on. My father lost his dad when he was about the same age. He died in the mid 1930s from surgical complications associated with a bleeding ulcer. My dad’s mom and his six siblings were compelled to confront the specter of eking out an existence on a potato farm in Idaho in the midst of the Great Depression. So he understood how traumatic the prospect of losing a parent at a young age could be.

When my parents came into my hospital room, I could tell they were not fully prepared for what they saw. One of my mother’s favorite descriptors for someone—including herself—who looks awful was, “death warmed over.” She later told me that I appeared to have been warmed over one too many times.

Neither of them sat; mom stood on my right while dad was on the left side of the bed. She asked most of the questions, while my father hardly said a word. They could see I was tired—my eyes were beginning to close—and knew I needed rest. Mom said they would come back later and then started to leave. My dad lingered for an instant, still not knowing what to say. And then he did something he had never done before.

He leaned down and kissed me on the forehead.

In that instant, I felt an overwhelming sense of peace and knew everything was going to be okay. Although I was not discharged from the hospital for another week, I did receive the job offer I had been counting on, accompanied by a fruit basket wishing me a speedy recovery. (I believe the firm acted quickly out of the belief that once I accepted its offer—which I did with alacrity—God would not take me lest he find himself on the receiving end of a lawsuit for unlawful interference with contractual relations.) We were also able to move forward with the purchase of our new home, and my health has never suffered for want of a gallbladder.

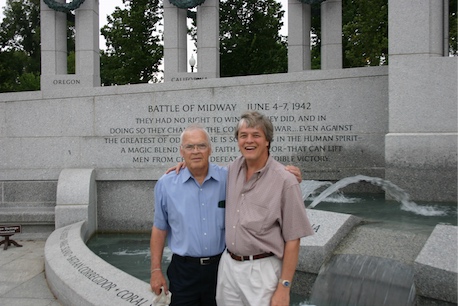

To the three men Don McLean admires most—the Father, Son and Holy Ghost—I would add a fourth: my father. After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he joined the Army Air Corps where he served as a navigator on a Northrop P-61 Black Widow night-fighter. Once the war was over, he married my mother, became a loyal scoutmaster, built a successful aviation insurance business from scratch, and, with mom’s considerable assistance, raised four reasonably well-adjusted boys.

Among other things, he passed on to me his love of books and music. In 2014, a few months before he succumbed to the ravages of Alzheimer’s disease, we visited him at the assisted-care facility in Champaign-Urbana where he lived. As planned, I played the piano for him and the other residents while they ate their lunch. The smile on his face and the gleam in his eye when his friends thanked him for bringing his son to brighten their day with music made all the years of practice worthwhile.

Thanks for everything, dad. And Happy Father’s Day.

If there is any immortality to be had among us human beings, it is certainly in the love that we leave behind. Fathers like mine don’t ever die.

Leo Buscaglia

Beautiful. Happy Father’s day.

Eric

What a lovely remembrance -it brought tears to my eyes. We so miss you and Margaret and our own dear fathers. We are so grateful for the legacy of faith and compassion they left behind!

HAPPY FATHERS’ DAY!

A harrowing medical story there . . . and then a lovely tribute to your father, thanks for sharing.

Thank you, Linda, Sarah and Jeff for your kind words.

One of the things I like best about Father’s Day and Mother’s day is that they invite us to look back, remember, and reflect upon the past and how we have benefited from those who came before. Invariably those legacies are flawed, but if we can’t forgive the mistakes of our predecessors, then our children are not likely to forgive ours.

I always like to spend Father’s Day and Mother’s Day in a spirit of gratitude and reading this put me in the perfect spot for that. So I can be grateful for having such a great father myself who has taught me hard work, the importance of education, serving others and so much more. I can see the legacy that has brought all of these things through generations and I hope I can pass a fraction of those wonderful attributes on to my own children.

Thanks, Bud. I could not have asked for a better Father’s Day gift (but I still expect a present every year?).

What a wonderful wonderful tribute. You were certainly blessed with a father who loved and cared for you. And, as someone who’s had gallbladder problems I can only deeply to sympathize with the excruciating pain you must of gone through. These sorts of stories make me lose my faith in the medical profession.

Thank you for your kind words, Karen. I was truly blessed with wonderful parents.

And, yes, this experience did shake my faith in the medical profession. The only person who seriously gives a damn about your health, I have learned, is you.

I think you can add your wife and children as people who care about your health but my faith in the medical profession is very tarnished due to my own experiences. I do believe that it is vital for anyone in the hospital to be accompanied by a “pushy” well advocated.

Those are good points Karen—especially the part about the “pushy advocate.”